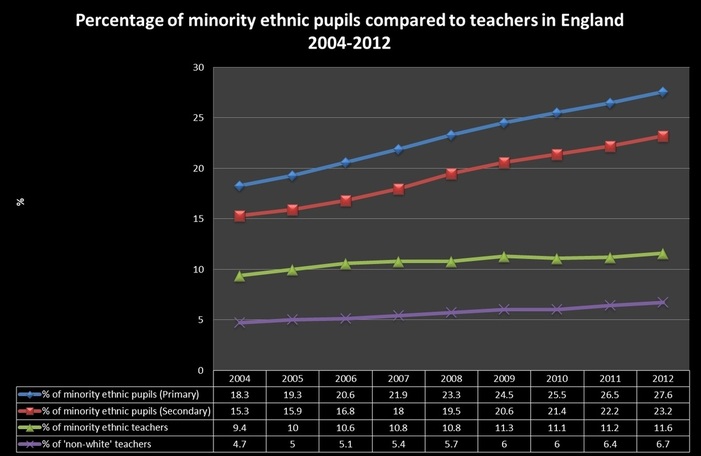

This year’s data highlighted the stark realities facing the English education system, whereby the profession remains overwhelmingly white at a time when the pupil population is becoming increasingly diverse. Statistics from the report show that 94.4% of Heads of publically funded schools are from a ‘White British’ background. However, considering the fact that this means the remaining 5.6% ‘ethnic minority’ category also includes 1.8% of Heads from ‘Any other white background’ and 1.3% from ‘White Irish’ background, the figures are even more alarming if you look at the ‘non-white’ representation of Heads which stands at a paltry 2.5%. The situation regarding teachers is a little better with 88.4% of teachers coming from ‘White British’ backgrounds overall, but again the figures drop considerably when looking at just ‘non-white’ teachers, which represent only 6.7% of the teaching workforce. This is an increase of 0.3% on last year. Behind this headline data, the report also shows that there are higher percentages of minority ethnic teachers and senior leaders in the London region, highlighting considerable regional disparities too.

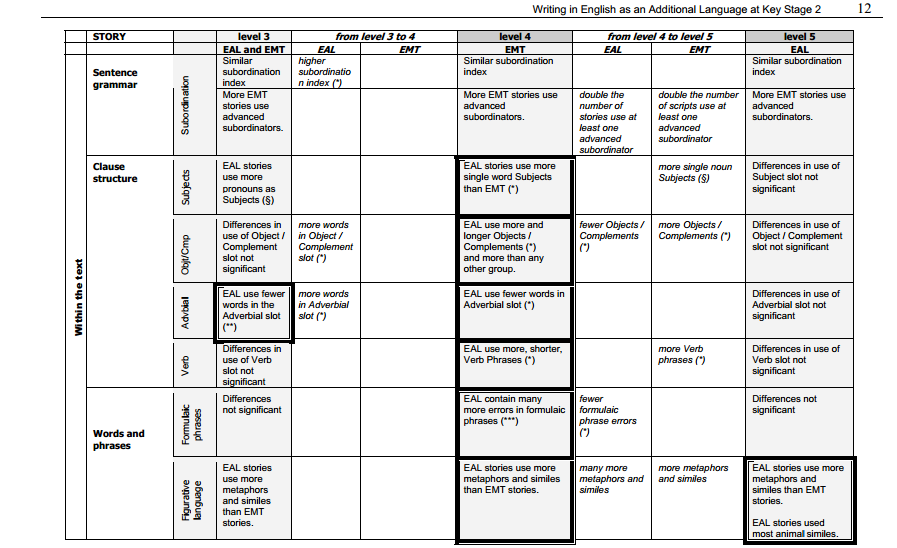

I was disappointed with these figures, so decided to take a longer view of the situation rather than judging the improvements over one year. I therefore went through each annual ‘School Workforce’ report and was able to go back as far as 2004, when the first set of disaggregated data became available. I also wanted to look at what was happening in our schools in relation to the pupil population and was able to get the figures for the minority ethnic pupil profile from the annual ‘Schools, pupils and their characteristics’ reports for the same period. My findings are presented in the graph below, which plots the percentage of England’s minority ethnic pupil profile separately by Primary and Secondary phase from 2004 to present, along with both its minority ethnic (green line) and ‘non-white’ (purple line) teacher profile over the same period.

DfE: Schools, Pupils and their characteristics, Statistical First Release for individual years 2004 -2012

DfE: School Workforce in England, Statistical First Releases for individual years 2004-2012

The graph doesn’t need much commentary because the visual representation tells the tale quite vividly. What these figures reveal is that the percentages of minority ethnic and ‘non-white’ teachers have increased more or less every year leading to an overall 2% gain over this period. However, as can be seen in the graph these increases are occurring at a painfully slow rate. Certainly during the past eight years the percentage of minority ethnic pupils has increased at a faster rate, so that the gaps are widening considerably year on year and will continue to do so unless some decisive action is undertaken.

For many years in England there has been a recognition and understanding by policy makers of the many benefits which can accrue from having a school workforce which is reflective of its pupil population. It has also been recognised that minority ethnic teachers can play an important role in ensuring that all pupils get a more balanced view of society and as far back as 1985, when I first entered the teaching profession, The Swann Report and later the Cantle Report in 2001, highlighted the need to ensure that the teaching ethos of each school reflected the different cultures of the communities served by society and that the lack of ethnic minority teachers in schools needed urgent attention. The now abolished Teacher Development Agency (TDA) oversaw a number of initiatives through which Initial Teacher Training (ITT) institutions were actively encouraged to recruit and retain minority ethnic staff in schools. The National College similarly has led a number of initiatives to encourage better representation of minority ethnic teachers to progress to senior leadership levels, such as the Equal Access to Promotion (EAP) and Investing in Diversity (IiD) Programmes. During this time there have also been a number of important reports commissioned to look in depth at the disparities that exist and the reasons for this, such as joint report by NASUWT and NCSL entitled ‘The leadership aspirations and careers of black and ethnic minority teachers’ undertaken by The University of Manchester. This report along with several others provides useful information to ascertain the issues and possible ways forward for interested parties, although generally there is a dearth of research in this area both in England and internationally.

This issue is not only pertinent to England as many countries across the world are also grappling with similar issues to varying degree of success. An OECD report called ‘Educating Teachers for Diversity: Meeting the Challenge’ in 2010, explores the concepts underlying diversity in various contexts across the world and the challenges involved in creating an evidence base to guide policy makers. This report focuses on two key areas:

· Preparing all teachers for meeting the needs of an increasingly diverse pupil population and

· Ensuring the school workforce is representative of the pupil population

It urges schools and education systems to ‘treat diversity as a source of potential growth rather than an inherent hindrance to student performance………’ and argues for a paradigm shift from homogeneity, to heterogeneity and finally to diversity by moving along a continuum, whereby difference is not acknowledged under homogeneity, differences are seen as a challenge to be dealt with under heterogeneity, to difference seen as an asset and opportunity under diversity. In England, the challenge for us is to move from heterogeneity to diversity and accelerate our efforts in in this endeavour.

With the rapidly changing education system within England, it seems that the current developing autonomous school system led by Teaching School Alliances and their partners could provide an opportunity to embrace these issues by ensuring that decisive action is taken at a local and regional level to make the school workforce more representative of the pupil and communities they serve. Teaching Schools have been given the remit of recruiting and retaining the best teachers and leaders and providing high quality Continuous Professional Development (CPD) opportunities for staff at all levels of career progression. They also have a remit to focus on succession planning issues. The National College Teaching School handbook in the section ‘Diversifying School Leadership’ gives clear pointers for serious consideration. Dependent on the understanding and expertise of diversity matters within individual Teaching School Alliances, which may or may not be a current area of strength, there is the powerful potential of taking forward what has already worked well by successful ITT institutions in this area and ensuring this is embedded in newer programmes such as Schools Direct, which are increasingly being delivered locally by schools. It also provides an opportunity to carefully look at the existing programmes being delivered through Teaching Schools to ensure that action is taken to recruit and retain minority ethnic teachers and where gaps in provision are evident, bespoke solutions are developed.

With careful analysis of local needs in relation to diversity matters there is the unique possibility for each Teaching School Alliance to develop a clear and cogent strategy of building on the existing best but also innovating to fill existing gaps, so that there is acceleration in percentages of ethnic minority teachers and Senior Leaders at local and regional level, in line with the paradigm shift argued for within the OECD report. This would enable England to become a world leader in this area for other countries to emulate.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed