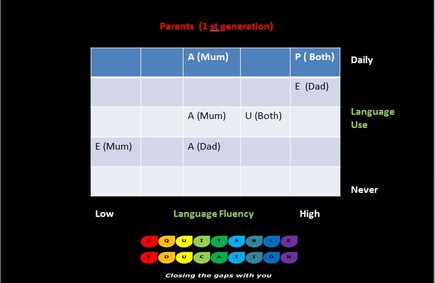

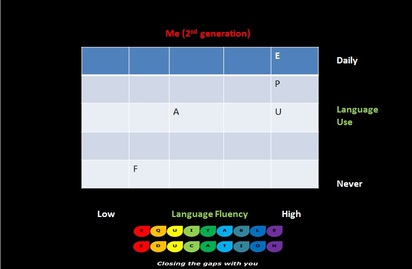

I shared my own experiences of bilingualism within the family by using a grid produced by Professor Francois Grosjean to show how language use and language fluency can vary across generations. In Professor Grosjean’s grid language use is presented along the vertical axis (from never used at the bottom all the way to daily use at the top) and language fluency is on the horizontal axis (from low fluency on the left to high fluency on the right.

I started by sharing information on the language use and fluency of my parents. This is shown in the grid below with E= English, P =Panjabi (mother tongue), U=Urdu, which is used as a Lingua Franca in the Indian sub-continent and A= Arabic, often used for religious purposes. The use of language and fluency is, I believe, quite typical of many first generation members of the community who migrate to a new country, irrespective of actual languages and was certainly quite common amongst my parent’s generation who came to live and work in England in the 1960’s. As you can see from the grid it also shows quite interesting differences between male and females.

The lack of a languages strategy for schools has been lamented by many and recently with the introduction of the EBacc languages are being given a higher profile and gradually the numbers of pupils studying languages is increasing. Sadly, though much of these positive moves still focus on Modern Foreign Languages and creates a false dichotomy between MFL and so called ‘Community Languages’ many of whom ironically are world languages and have many millions of speakers across the globe!

This lack of joined up ‘Languages Strategy’ for education continues presently yet it is a missed opportunity for successive policy makers as it to fail to tap into and embrace the many positive aspects of bilingualism. This month’s British Council Report ‘The Languages for the Future’ report identifies a range of languages [1], including many spoken by migrant communities as being essential to the UK over the next 20 years. These languages were chosen based on economic, geopolitical, cultural and educational factors including the needs of UK businesses, the UK’s overseas trade targets, diplomatic and security priorities, and prevalence on the internet. But, according to an online YouGov poll of more than 4000 UK adults commissioned by the British Council as part of the report, three quarters (75%) are unable to speak any of these languages well enough to hold a conversation. It certainly seems time for policy makers to pay heed to the latest research and consider how it can support the learning of languages amongst its population, including the maintenance of languages already spoken within communities.

[1] Spanish, Arabic, French, Mandarin Chinese, German, Portuguese, Italian, Russian, Turkish and Japanese

RSS Feed

RSS Feed