The announcement made by the DfE last week that the Teaching Agency and The National College are to merge under the leadership of Charlie Taylor, will mean that for the first time there will be one executive agency responsible for the recruitment, supply and development of both teachers and leaders for schools in England. The new agency (with a name to be determined) will therefore play an important role in ensuring the highest quality of teachers and leaders for our schools. The purpose of the new agency which will be operational from the end of March this year, is to enable the best leaders and best teachers to work together to develop a self-improving school system and be responsible for the recruitment, supply, initial training and development of teachers. The new agency, will also oversee the development of a cadre of system leaders such as National Leaders of Education (NLE’s), Local Leaders of Education (LLE’s), Specialist Leaders of Education (SLE’s) and Teaching Schools whose remit is to focus on leadership development, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) and school improvement to address under performance across the education system.

This merger provides a golden opportunity to refocus energy on the current gaps in attainment in England by enabling system leaders and teachers to develop the requisite skills, knowledge and understanding to address this key challenge, which permeates within and across schools, thereby contributing to the long tail of underachievement.

Closing the gaps for different groups of pupils is high on both the DfE and Ofsted’s agenda, with schools being given considerable amounts of additional funding to address the gaps in attainment that exist for pupils who are eligible for free school meals (FSM) through the Pupil Premium[3]. However, although no one disputes the impact that poverty has on attainment which remains a major factor in preventing pupils getting to age related national expectations, there are many other factors such as a pupil’s gender, ethnicity, special educational needs, disability and language background which can and do impact on attainment. Indeed, for many pupils it is not just poverty alone, as many of these groups tend to have rates of FSM than average, but an amalgamation of these factors or “intersectionality” which impacts on outcomes.

The new agency will be responsible for recruiting and providing a ready supply of high quality teachers and leaders, with Teaching School Alliances taking on the role of providing high quality professional development. In order to maximise the potential of the teaching workforce it is essential to not only ensure that staff have high levels of knowledge and understanding of the subjects they teach and are able to deliver high quality teaching which impacts on learning and pupil progress, but also it is equally important that they are able to meet the specialist needs of the range of pupils for whom closing the gap remains an issue too. The acquisition of these specialist teaching skills and in – depth understanding and knowledge of individual needs of a range of pupils should be developed alongside teacher’s subject teaching skills from the outset of their career. Presently, there are many teachers who are able to personalise their teaching so that it impacts on all learners in their class and their teaching is classified as “outstanding”, using Ofsted terminology. Others however can find this a challenge and feel less confident in meeting the needs of the wide range of pupils who are currently not performing in line with national expectations. Despite this, they are expected to deliver high quality teaching which impacts on pupil’s learning so that they make faster than average rates of progress in an academic year. In order for them to deliver high quality teaching, specialist demands are made of the teacher for which they may not have received the necessary training, support or professional development opportunities at key points of their teaching career.

Using the example of pupils for whom English is an additional language (EAL). This group has been chosen to illustrate the issue facing some teachers, although this would be equally applicable for other closing the gap pupils such as those with special educational needs, disabilities, the more able, certain minority ethnic pupils, and cutting across gender and socio-economic status too.

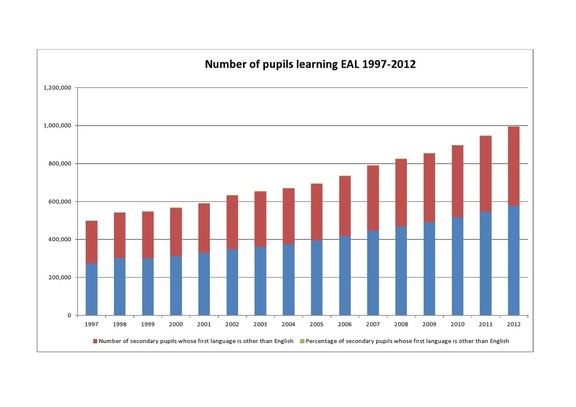

The annual census taken in January 2012 by the DfE showed that there are approximately 1 million pupils whose first language is other than English. The numbers of EAL pupils have more than doubled since 1997 when the first census was taken. The graph below illustrates the increasing number of EAL pupils in primary and secondary schools in England from 1997-2012.

[1] “How the world’s best performing school systems keep coming out top”, Morshed M and Barber M, McKinsey and Co. 2007

[2] Seven Strong Claims About Successful School Leadership, Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A. and Hopkins, D, NCSL, 2006.

[3] When the Pupil premium was introduced in April 2011, schools received an additional £488 for each of its pupils eligible for free school meals. In April 2012 this was increased to £600 with further increases announced for this year taking it to £900, amounting to £1.65 billion in the financial year 2013-2014. By 2012 the Pupil premium will be worth £2.5 billion of additional money coming into schools.

The graph shows that in 1997, the percentage of pupils learning EAL in the primary school population was 7.8%. Over 15 years this percentage had more than doubled to 17.5% by 2012. In secondary the figures were 7.3 % in 1997 compared to 12.9% in 2012. The census also showed a rich tapestry of languages being spoken by EAL pupils in English schools with over 360 different languages being recorded. The percentages of pupils classifying themselves as EAL of course varies considerably from school to school and LA to LA, with Tower Hamlets and Newham LA’s having the largest recorded at 74% and 71% respectively and other large LA’s such as Birmingham with 40 %. In contrast LA’s such as Halton and Redcar& Cleveland only have 0.8% of EAL pupils. Projected demographics show that the number of EAL pupils in schools will continue to grow at comparable rates over the next decade and beyond.

However, despite the growing number of EAL learners in school there appears to be no clear nor focused strategy at a national level to address EAL learner’s needs at a time when there can be significant attainment differences between pupils for whom English is an additional language and for those who speak English as their first language. The largest differences between the two are more pronounced at the Early Years Foundation Stage with gaps narrowing to some extent by KS4 as EAL pupils learn the academic English language required to be successful in examinations. However, it should be noted that there still remain significant differences in attainment with EAL pupils in inner and outer London attaining much better than their peers in other regions such as Yorkshire & Humber where large and persistent gaps in attainment continue to exist.

One of the ways EAL learner’s needs should be addressed is by ensuring that teachers are better trained so that they have the requisite knowledge, skills and expertise to teach EAL learners. EAL learners are not a homogeneous group and can have a wide variety of needs. Therefore, it is essential that teachers understand the wide variety of EAL needs and how they can support pupils across all four skills of speaking listening, reading and writing in the lessons they teach, particularly in the academic English required to be successful in examinations. The challenge for teachers is to keep the cognitive demands of the lesson to high level by providing contextual and linguistic support to the EAL pupils in their class. Many teachers will never have had any training or CPD to support them in teaching EAL pupils over the course of their career and as EAL has not been a subject specialism in teacher training for many years now, access to training can be extremely varied, with some Initial Teacher Trainers (ITT) providers preparing their students very well and others not touching this area at all.

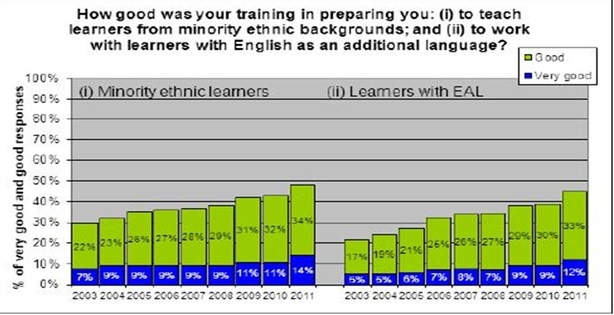

The above picture is supported by the annual surveys undertaken by the then Teacher Training Agency (TDA) of Newly Qualified Teachers (NQTs) who had successfully completed their ITT. Over the years, whilst the training of NQT’s in this area has improved with approximately 45% of NQT’s stating that their training was good or very good in 2011 – more than double that in 2003, there still remain more than half of new entrants to teaching feeling less well equipped in this area. The graph below shows percentage of NQTS who felt there training was good or very good in preparing them to teach EAL learners and minority ethnic pupils from 2003 – 2011.

With the shift in emphasis from Universities and Colleges of Education to Teaching Schools as providers of ITT via the new Schools Direct Programme, the issues highlighted by the TDA annual survey will need to be closely monitored and addressed. Teaching Schools will need to ensure that these new school based programmes prepare and equip NQTs better than before so that they are able to teach currently under –performing groups to the highest standard.

The new Teacher Standards 2012 outline the teaching and professional conduct expectations of all teachers. Many of the teaching standards are implicitly relevant to EAL pupils and other groups of pupils too, but standard 5 explicitly states:

“A Teacher must ……….

· have a clear understanding of the needs of all pupils, including those with special educational needs; those of high ability; those with English as an additional language; those with disabilities; and be able to use and evaluate distinctive teaching approaches to engage and support them”.

In this context it is essential that we are preparing all our teachers to understand the needs of our closing the gap groups and our diverse pupil population. Through relevant training and CPD, including Joint Practice Development (JPD), continuing with the example of EAL pupils they can gain in-depth understanding of second language acquisition theory and pedagogy and use appropriate teaching strategies to enhance their own teaching. This would impact on closing the current gaps in attainment that exist for too many EAL pupils, many of whom are of now of second and third generations of communities settled in England.

Focusing now on the role of system leaders such as NLE’s, LLE’s and SLE’s who are beginning to drive the development of the self-improving school system. They too have an important role to play in closing the gaps for different groups of pupils. These system leaders in their various roles are providing support to other schools. Many of the schools they are likely to support, albeit not all, have higher concentration of pupils for whom closing the gap remains an issue. The schools they are supporting may be situated in very geographically different contexts to their own schools with the school community facing a plethora a challenges not experienced by the more successful school. They too should be given the opportunity to develop the specialist skills in addressing the needs of different pupil groups for whom closing the gap is an issue, as they may not have had experience of addressing these pupil needs within their own school context or career due to the nature of their pupil cohorts. This additional professional development opportunity which could be delivered by Teaching Schools through their existing leadership development programmes such as NPQH, NPQSL, NPQML[1] or alternatively through bespoke programmes which address the needs of under- performing groups of pupils within their locality. This would no doubt enhance the proven track record and leadership skills these system leaders have already gained in their own schools thus enabling them to be more effective when supporting schools in different contexts.

Many Teaching Schools at the moment are running the “Outstanding Teacher Programme” and the ”Improving Teacher Programme” which are without doubt having an impact on improving the quality of teaching in schools. However, these programmes could be even more effective if teachers on these programmes were able to develop the specialist skills required to address the needs of closing the gaps groups alongside generic high quality subject skills. This would mean that teachers were better prepared to teach the actual pupils in their classes and the communities their schools serve. In the case of The London Challenge where these courses were first developed and delivered, there was some flexibility to adapt these courses to meet a variety of needs on this basis.

These are exciting and opportune times to make educational changes for the better and if the self-improving school system is to impact on current gaps in attainment not only in terms of EAL pupils but other underperforming groups too, then the new agency has the opportunity to take proactive action to address these areas in an ambitious way by incorporating the suggestions above into all aspects of the new agencies work. This would ensure that the new agency was preparing its teachers and leaders for the current and future needs of its pupils and by doing so realising the ambition of raising standards of attainment across the board.

[1] The newly revamped NPQH, NPQSL and NPQML does give aspiring leaders the opportunity to study modules on Closing the Gaps and Achievement for All. However, it is only the NPQSL where the Closing the Gap module is essential.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed