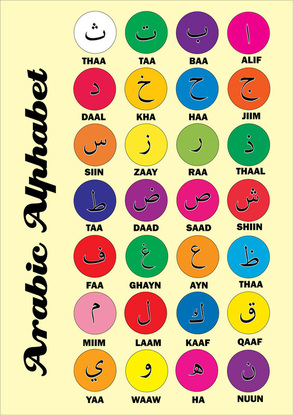

Due to my own interest in languages and multilingualism in a particular, I decided that I would ensure that my own children would be fluent in their mother tongue Panjabi and become proficient in Urdu (written in the Perso- Arabic script, hence my nephews comments on the Arabic Alphabet) because of the valuable role that it plays as a Lingua Franca [1] across the Indian subcontinent, not mentioning its popularity across the world for many reasons, including its prevalence in Bollywood movies many of whom use Urdu and Hindi. I therefore, made a conscious effort to give my children the opportunity to learn both languages in a natural way as possible, ensuring that they had a wide range of bilingual books at their disposal to reinforce the use of both Panjabi and Urdu within the family. What I found surprising, especially in the case of my son, who is now 15 years old was that within a term of going to Reception, more or less the same age as my nephew, he refused to speak in any language other than English. Now as it happens, both my children and now my nephew go to the same school. The school is a larger than average primary school, with very low levels of FSM and approximately 12.5 % of EAL pupils. They generally provide a good education and in their own way promote diversity, certainly more than when I was at school but despite this the effect on my nephew was the same as it has been for me and my children. The net result of this is that potential bilingual or even multilingual children are gradually undergoing ‘language loss’. This phenomenon is occurring across many settled communities. At best children and young people growing up are only able to develop receptive skills in languages used within the community but are not able to use these skills productively as English becomes the dominant languages which is increasingly used in all domains.

This anecdotal story illustrates the powerful monolingual message which continues to play a dominant role in England today. Ironically, this is in strong contrast to the message given by politicians and the media which states that communities choose NOT to speak English. I don’t think I have ever come across anyone who has resisted the need nor discounted the importance of learning English. It is disingenuous to talk about settled communities not speaking English, especially when extensive research from different parts of the world show that many communities suffer language loss within a generation as in the case in personal example given above. Indeed, a language survey undertaken by www.ethnicpolitics.org shows how English is now used by more bilingual communities within the home context too. In their initial survey which was undertaken in 1997, 56% of the minority ethnic members surveyed stated that they used English at home compared to 44% who stated they did not. There were of course underlying differences for the various different communities. By 2010 the responses to the same survey showed that this trend has completely reversed with 64% of minority ethnic members now stating that they used English at home compared to 36% who said they did not, with these significant changes having taken place over a period of just 13 years.

Furthermore, the critics who like making a fuss about the learning of English choose to ignore the fact that the 2011 Census showed that of the 51,005,610 English population taking part in the census (residents aged three and over) 46,936,780 of them had English as their main language. For the remaining 4,068,830 for whom English was not their main language, 3,224,830 spoke English either very well or well, with a further 709,862 stating they could not speak English well. Only a small proportion of the overall population, a mere 133,983 stated that they could not speak English. [2]

More importantly for me the issue is that you don’t just have to know one language. It is possible to be proficient in more than one language without it being detrimental to learning, which sadly was the WRONG view perpetuated in the days when I was growing up. Indeed, there are many benefits that accrue from being bilingual, notwithstanding the cognitive benefits which teachers could use to aid learning in the classroom. We really do need to ensure that our schools are more supportive of the learning of languages, both Modern Foreign languages and ‘community languages’. Sadly, the new proposed MFL national curriculum proposes a hierarchy of status for languages in which the languages spoken by many of our settled communities are not recognised at all. This is just plain wrong and it is such omissions in practice and policy which so powerfully give the message to all children, whether monolingual or not that languages other than English are not important, unless of course they happen to be on the ‘list’ which then are reserved for the elite few who are deemed capable of studying languages. It’s about time we started valuing all languages, so that we move away from the deficit approach that is common in England and build upon the rich linguistic capital that exists within our communities.

Just as a final note to ponder. We could take a broader view of many of these so called ‘community languages’ which are spoken by millions of people in the world. Take for example the three Indo-Aryan languages mentioned in this posting, which I like many others of my generation, are lucky to have as part of our linguistic capital – Urdu, Hindi and Panjabi. These three languages are mutually intelligible. According to the total number of speakers for these languages in 2007, there were 295 million speakers of Hindi, 96 million of Panjabi and 66 million of Urdu in the world.[3] If you add these three languages together you come to a grand total of 457 million speakers, which is the equivalent of 6.89 % of the world’s population. In the same year, the total number of speakers of English was 365 million or 5.52% of the world population. Not so much of ‘community languages’ after all, when you take a wider global perspective.

This should certainly give us food for thought as we are increasingly required to navigate in a globalised world, where the language competencies that are required are more varied and which mean that we cannot continue to be solely reliant on English is a dominant language. It's time for us to wake up and embrace the fact that over half of the world’s population is bilingual and it is the norm across all social groups and ages and many of the languages that could be used naturally by our children are gradually being taken away at a loss to them and society as a whole.

[1] The use of Panjabi, Urdu and Arabic within Pakistani heritage community is not explored here but will be covered in another posting later, as well as the relationship between Urdu, Hindi and Panjabi.

[2] Source Office for National Statistics, 2011 Census Proficiency in English, local authorities in England and Wales (Excel spreadsheet) http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/search/index.html?newquery=english+language+use

[3] Source http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_languages_by_number_of_native_speakers

RSS Feed

RSS Feed