Over the last few years there has been much emphasis placed on closing the socio-economic gaps in attainment between pupils who are eligible for free school meals and hence receive additional support through the Pupil Premium Grant and those who do not. This is a laudable policy ambition and is worthy of concentrated effort by all of us involved in educating children and young people. However, as with anything, the issues surrounding the closing of the attainment gaps are much more complex than just socio-economic deprivation. In his ground breaking report for Ofsted in 2000 entitled ‘Educational inequality: mapping race, class and gender. A synthesis of research evidence’ Professor David Gillborn showed how these three characteristics impacted on outcomes for different groups of pupils.

3 Comments

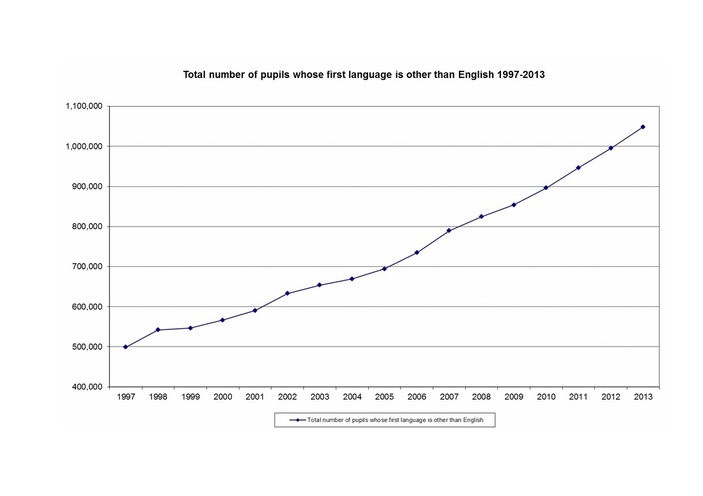

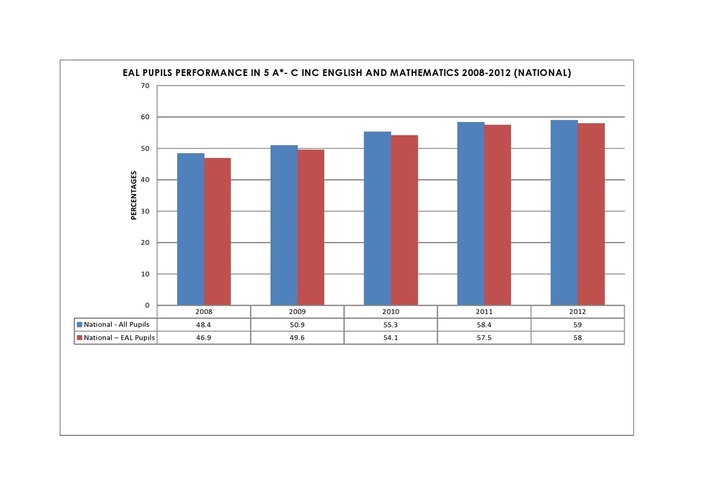

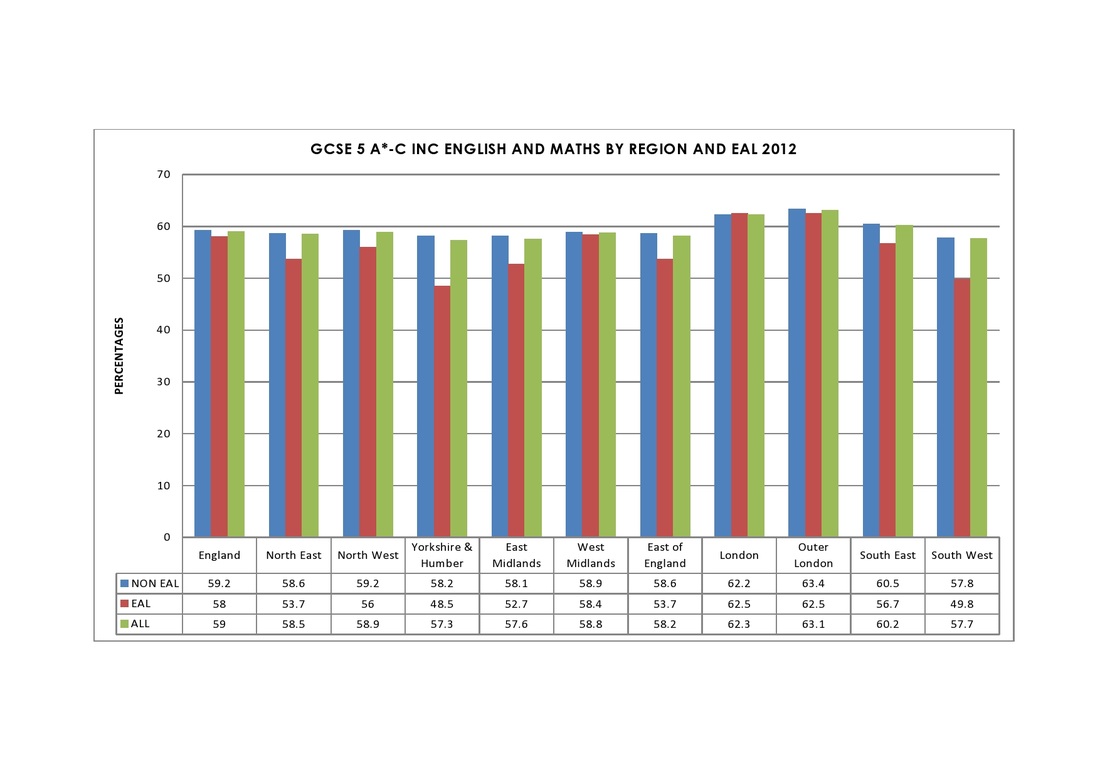

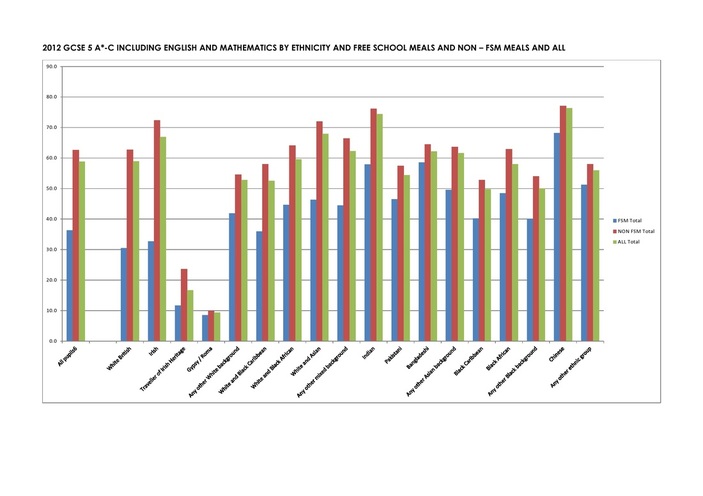

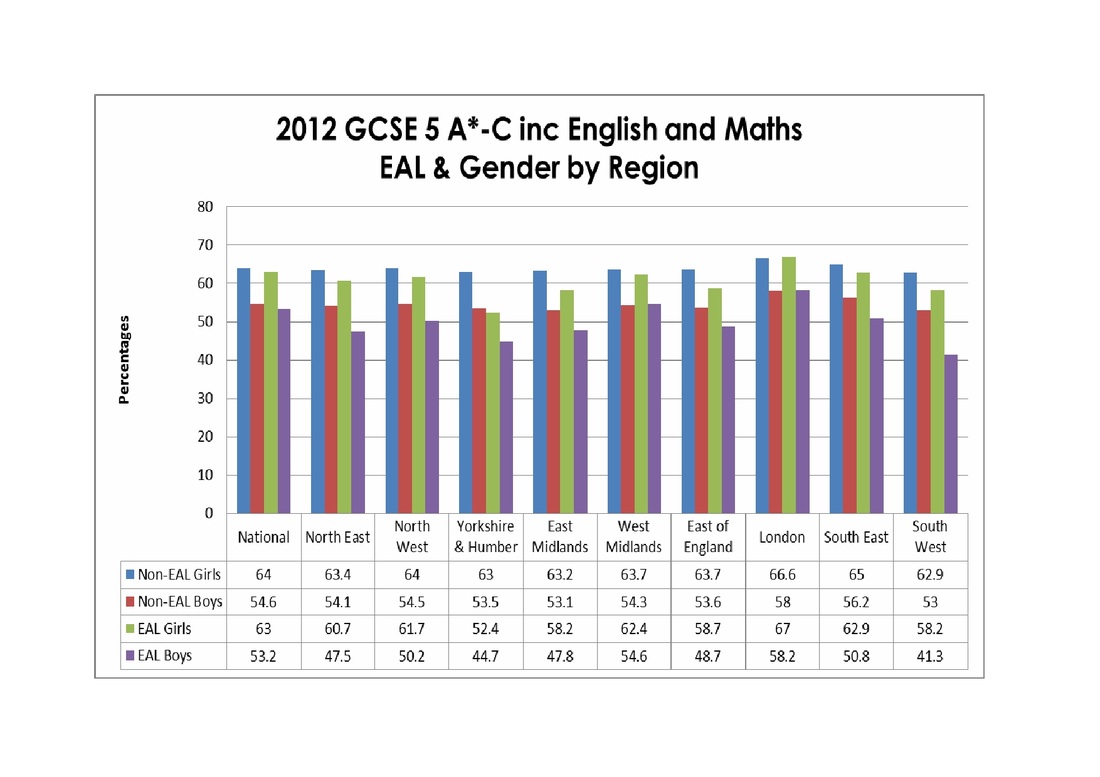

I am currently writing a paper on the present situation with regards to EAL pupils in England, which will cover the following: · Provide an overview of the official approaches to EAL over the past 30 years or so, · Briefly outline associated research into EAL pupil’s both national and international, · The current attainment of EAL pupils in England · Highlight examples of best practice in schools across regions and LA · Stress the urgent need for a more nuanced and focused strategy for pupils for whom English is an additional language at a national level · Outline recommendations The intended purpose of the paper is to encourage reflection, debate and forward strategy at a time when the current education system is undergoing considerable change leading to both potential opportunities and considerable challenges. In such situations there is the strong likelihood that the needs of some groups of pupils are missed especially when the spotlight is shifted to other groups who are deemed more worthy or more in vogue, leading to unnecessary binary approaches to raising attainment. This blog posting summarises some of the key headlines of this paper. The DfE recently released the latest statistics on the number of pupils for whom English is an additional language (EAL). These figures show that there are now over 1 million pupils whose first language is other than English, with the percentages in primary standing at 18.1% compared to 17.5% last year and 13.6% for secondary showing a 0.7% increase on last year. These annual increases show the growing number of EAL pupils in schools in England and are illustrated in the graph below: The trend shows that the numbers of EAL pupils are likely to continue to increase. As a result teaching EAL pupils is now an issue for all schools at a time when many professionals within education report that they do not feel well trained in addressing pupil’s EAL needs (read my earlier blog on EAL and ITE &CPD needs here). The attainment results over the past few years have shown that outcomes for EAL pupils have improved significantly leading to the attainment gaps virtually closing at a national level in terms of the gold standard 5 A*-C including English & Maths grades at GCSE. The graph below shows how the attainment gap at a national level has virtually disappeared over the past five years. These results for the last five years show a vast improvement compared to previously when most EAL pupils were significantly languishing behind their peers. Just a generation ago it was routine for bilingual pupils to be sent to separate language centres to learn English before being admitted to schools. This gradually changed to EAL pupils being sent to language centres within schools and being taught separately until it was felt that they would be able to cope with the mainstream curriculum of their peers. If EAL pupils were extremely lucky then they may have made it directly into the mainstream, escaping the need to receive an alternative curriculum but were often left to sink or swim, without any support or appreciation of their EAL needs. Nowadays these practices would be deemed abhorrent and totally going against well- known research of how bilingual pupils acquire and learn languages. Although these incidents happened approximately 25 – 30 years ago and illustrate the distance that has been travelled so far, they also highlight the journey which still needs to be travelled, until we get to a situation whereby all teachers have the understanding, knowledge and skills to address the needs of EAL pupils within the mainstream context and deliver high quality teaching and learning to enable all EAL pupils attain national expectations. It therefore seems appropriate to briefly take stock of where we are now in relation to meeting the needs of pupils for whom English is an additional language in England and look at the potential of where we should be in the very near future. I have listed a few key headlines below: · At national levels gaps are closing as the graph above shows. These results also mean that some of the powerful negative myths that have perpetuated in relation to bilingual pupils and their attainment are being exploded, resulting in the fact that bilingual pupils can and should achieve academic excellence as a matter of course. · Better outcomes in attainment mean that more EAL pupils have the potential to accrue the benefits of higher education. This should contribute to better opportunities for gainful employment and improved life chances resulting in economic, social and health benefits for many more community members in the future. · Generally most minority ethnic pupils have higher proportions of pupils for whom English is an additional language, with the exception of Black Caribbean pupils. This means that the positive aspects of being bilingual such as those outlined by many academics such as Jim Cummins, Colin Baker, Stephen Krashen, Tove Skutnabb- Kangas and more recently Ellen Bialystok can be used as a lever to support the learning of minority ethnic pupils currently not performing in line with their peers nationally. · Indian and Chinese pupils have been performing much higher than their peers for many years now. Both of these groups have high proportions of bilingual speakers, with over 80% of Indian pupils and 73% of Chinese pupils speaking English as an additional language.[1] More recently the performance of Bangladeshi pupils nationally has also accelerated with impressive performances. Previous reasons cited for Indian and Chinese pupils academic success have been attributed to lower rates of free school meal eligibility in these groups at 12% for Indian pupils and 14% for Chinese pupils. However, the performance Bangladeshi pupils, with one of the highest free school eligibility figures at 52%, add to the growing body of evidence which shows that pupils eligible for free school meals also perform very highly, setting the precedence for others to follow. · There is growing evidence which is exploding many of the myths surrounding EAL pupils. An example of this of is the recent research undertaken by Professor Sandra Mc Nally et al from the London School of Economics, Centre for the Economics of Education. Their research shows that EAL pupils do not negatively impact on standards for non-EAL pupils. For further details read my previous blog here) HOWEVER, despite the seemingly positive picture emerging at a national level, there remain significant CHALLENGES · There are extreme variations in EAL pupil’s attainment by region which the national figures mask. Nationally 58% of EAL pupils in England achieved 5 A*- C in English in Mathematics in 2012. However, EAL pupils in London performed 4.5 percentage points higher at 62.5% compared to those in Yorkshire & Humber who performed nearly 10 percentage points lower at only 48.5%. The graph below shows the regional variations in EAL pupils attainment 5 A*-C in English and Maths in 2012 [1] Figures cited are from ‘Ethnicity and Educational Achievement in Compulsory Schooling’ by Christian Dustmann, Stephen Machin and Uta Schonberg in The Economic Journal 2010. · EAL pupil’s performance within particular LA’s shows further huge variations in attainment with only 32.7% of EAL pupils achieving the gold standard at GCSE in Hereford LA compared to 82.8% of their peers in Kensington and Chelsea or 82% in Sutton. These huge disparities which continue to exist in different LA’s show the necessity to look beyond the national picture. Presently, where you live in England seems to exert a great influence of your educational outcomes which is morally unacceptable. · The success in closing of the gap of EAL pupils nationally can be attributed to a large extent to the higher performance of EAL pupils in London and West Midlands, where there are larger concentrations of EAL pupils, with improvements in London largely due to the success of ‘The London Challenge’. Amongst the various strategies which have been cited in accounting for the success of the London Challenge, the Pan EAL London EAL Strategy is worth highlighting for particular attention. The Pan EAL London Strategy enabled LA’s to receive additional funding to support effective teams to provide support for EAL pupils and to spread this expertise across London. The effectiveness of this work has been highlighted by M Hutchings and A Mansaray in ‘A review of the impact of the London Challenge (2003-8) and the City Challenge (2008-11)’ submitted as evidence to Ofsted’s ‘Access and Achievement’ Review a few months ago. · There are further variations in EAL pupil’s performance when looking at other characteristics such as ethnicity, socio-economic background and gender. Socio-economic gaps are more pronounced for White British groups compared to most ethnic minority groups. For some minority ethnic groups this is because non – free school meal pupils are less likely to come from families with higher socio-economic and professional backgrounds so the differences are less marked. Since national data is not available by ethnicity and EAL, ethnicity data can provide a useful indicator of performance, bearing in mind the intersections of ethnicity and EAL. The differences in performance by FSM eligibility and ethnicity are shown in the graph below: · Bangladeshi pupil’s performance nationally is skewed by the fact that over half of all Bangladeshi pupils live in London, with about a third located in Tower Hamlets alone. Tower Hamlets is one of the success stories and had an impressive 67.8 % of EAL pupils attain 5 A*- C including English and Mathematics in 2012 which is nearly 10 % above the national average. · There are considerable differences in attainment when looking at key stages with outcomes much lower for all minority ethnic and EAL pupils at the start of schooling and even at the end of primary for most groups compared to secondary where most of the gains for EAL pupils are made. This is well documented by researchers.[1] This means the potential outcomes of EAL pupils could be accelerated further if the progress seen in secondary, particularly at KS 4 was replicated in primary. · Gender differences also impact across various regions with EAL girls generally performing much higher than both non-EAL and EAL boys with the exception of the Yorkshire & Humber region where EAL girls performed marginally better than EAL boys but lower than non – EAL girls and boys. The graph below shows how EAL and Gender characteristics lead to extremely differential outcomes across regions with EAL boys in the South West performing the lowest in 2012 leading to a gap of 16.9% compared to their peers in London. [1] ‘The Dynamics of School Attainment of England’s Ethnic Minorities’by Deborah Wilson, Simon Burgess and Adam Briggs CASE paper 2006, ‘A Comparative Analysis of Bangladeshi and Pakistani Educational Attainment in London Secondary Schools’ by Sunder Divya and Layli Uddin 2007, Drivers and Challenges in Raising the Achievement of Pupils from Bangladeshi, Somali and Turkish Backgrounds by Steve Strand et al 2010 and Figures cited are from ‘Ethnicity and Educational Achievement in Compulsory Schooling’ by Christian Dustmann, Stephen Machin and Uta Schonberg in The Economic Journal 2010. · The regional differences are further compounded when looking at the performance in LA’s e.g. only 30 % of EAL boys and 39.3 % of EAL girls in Blackpool LA achieved the gold standard at GCSE last year. This is a stark contrast to the 81.7 % of EAL boys and 84.3 % of EAL girls in Kensington & Chelsea who achieved this benchmark.

· Another consideration is in relation to the performance of EAL pupils in mainly white LA’s. The issues are complex and may be down to the arrival of newer communities or lack of strategy and expertise in supporting EAL pupils particularly when EAL pupils are dispersed across an LA and are considered to be relatively small. It seems that we in England are at the cusp of making sustained changes in ensuring better educational outcomes for our EAL pupils, many of whom until recently have been languishing behind their peers. Taking a long view there is much to be celebrated and built upon. However, considering the fact that it has taken us over 30 years to get to this stage, with the gains by no means sustained nationally for all key stages and certainly not across regions and LA’s it is imperative that the best practice that is evident is disseminated as a matter of urgency to so that the momentum continues to be built upon. Sadly, although the national results for EAL pupils are applauded there is little if any emphasis on meeting the needs of EAL pupils in other areas or indeed in using flagship policies such as the Pupil Premium to stress the interlinked relationships that exist for EAL pupils and other characteristics such as free school meal eligibility. A more focused and nuanced policy at a national level is required to ensure that the potential of all EAL pupils, irrespective of ethnicity, socio-economic backgrounds and gender is realised and the impact of where you live or which you school you go to does not result in a lottery in achieving better educational outcomes. The headlines are based on a detailed paper which is currently being written by Sameena Choudry on EAL pupils in England and the need for a nuanced strategy to close the gaps. I have recently had the pleasure to become acquainted with Dr James S. Brown. Dr Brown is a Canadian who has over 40 year’s career in education in a variety of senior roles, including working in England. His research interest and expertise is in improving education, especially for those disadvantaged by existing educational systems. He has undertaken intensive research into the issue of the underachievement of boys and has published a book entitled “Rescuing our Underachieving Sons”, which provides an in depth analysis of the underlying issues based on intensive research and his own experience in education in both Canada and the England. His book also provides suggested strategies parents and the education system as a whole can deploy to raise boys achievement.

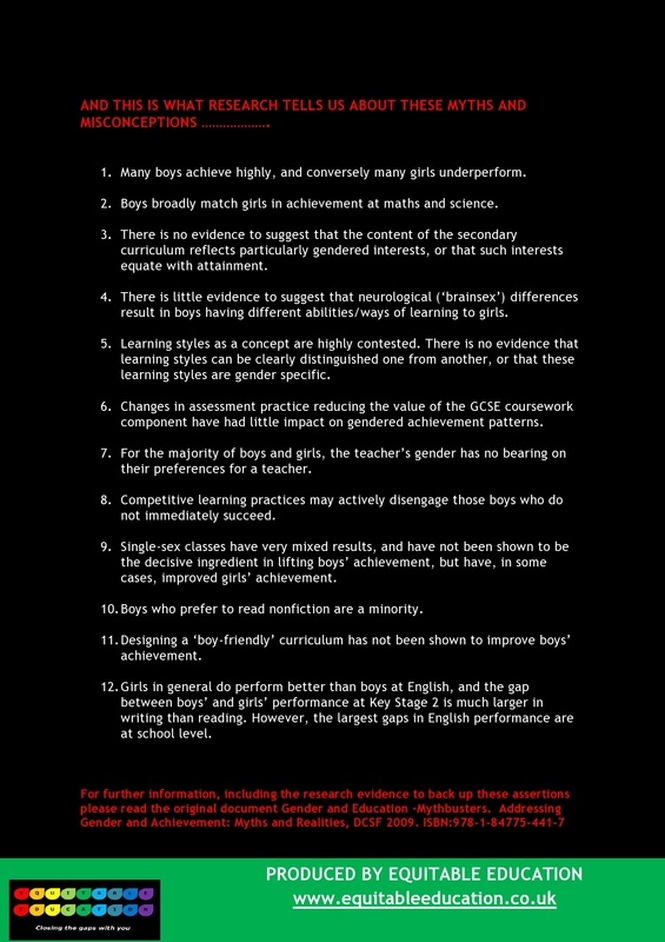

Dr Brown has also written three smaller booklets, based on his research and book. His second booklet entitled ‘How the education system can help boys to become achievers in school” is available to download here and covers the 4 major characteristics that tend to be common amongst achievers such as: 1. They come from more stimulating environments, where parents speak and read to them more, 2. They receive more support and encouragement from parents, teachers and society in general, 3. They have high self-esteem and more confidence in their abilities. 4. They work harder, not only because of their need to achieve, but also because they like what they are doing and are more engaged by it. The booklet provides detailed information on each of these four characteristics, as well as suggested ways in which parents can support their sons to become achievers. Dr Brown has kindly provided the booklet for readers of Equitable Education’s blog free of charge to download. Our thanks go to Dr Brown for generously sharing his research with us. We hope this will support colleagues in improving educational outcomes for boys in their schools. The ‘gender effect’ is a matter of concern not only for England but many countries around the world. As a result, gender and educational attainment continues to be the focus of research. Initially the focus was on ‘girls’ underachievement’ in the 1970’s but since the 1990’s, however, the discourse has shifted significantly to focus on ‘boys’ underachievement.’ This issue regularly preoccupies the minds of many politicians and parts of the media, and from time to time it gives way to a moral panic. However, in terms of inequalities in education it is worth remembering that class has over five times the effect and ethnicity has twice the effect compared to gender. [i] That is not to say that that the effect of gender is not still significant but it should be considered within this context. The actual issues affecting inequalities in education can be quite complex and to gain a better understanding of these issues it is important to look at how class, ethnicity and gender come together to interplay on educational outcomes. It is recommended that senior leadership teams and staff in school look holistically at the needs of their particular pupils and groups of pupils who are currently underachieving before developing strategies to address these needs. It is also worth remembering that there are more variations within the overaching groups of ethnic minority and pupils eligible for free school meals, as there are between them too, largely because groups are not homogeneous and have a wide variety of needs. This fascination with the ‘gender effect’ has resulted in many myths and misconceptions being perpetuated. For colleagues interested in addressing gender inequalities Equitable Education has produced the following Infographic exploding 12 myths and misconceptions commonly associated with gender. The Infographic has been based on the publication called ‘Education and Gender – Mythbusters. Addressing Gender and Achievement: Myths and Realities’ produced by the DCSF in 2009 and written by Gemma Moss, Becky Francis and Christine Skelton. [i] Gillborn D & Mirza H (2000), ‘Educational Inequality: Mapping Race, Gender and Class. A Synthesis of Research’. Ofsted London The realities to these myths are outlined below: The original publication ‘Education and Gender – Mythbusters. Addressing Gender and Achievement: Myths and Realities’ produced by the DCSF in 2009 and written by Gemma Moss, Becky Francis and Christine Skelton it is available here in PDF format for you to download. It includes further information, along with research evidence to back up these assertions.

We shall be coming back to this topic in future postings, so do visit our blog regularly to keep updated. In the meantime, should you require specialist advice and support in addressing educational inequalities in.your school, please do contact us at Equitable Education by e-mailing us on [email protected]k If you would like a PDF version of our Infographic to use in your school, please get in touch with us by using the e-mail above. We look forward to hearing from you. “Gender equality is not just about economic empowerment. It is a moral imperative. It is about fairness and equity and includes many political, social and cultural dimensions. It is also a key factor in self-reported well-being and happiness across the world. Many countries worldwide have made significant progress towards gender equality in education in recent decades. Girls today outperform boys in some areas of education and are less likely to drop out of school. But the glass is still only half full: women continue to earn less than men, are less likely to make it to the top of the career ladder, and are more likely to spend their final years in poverty”  Just a few weeks ago the OECD released a detailed report called Closing the Gender Gap - Act Now”. The report covers four key areas of gender inequalities ranging from general public policy, employment and entrepreneurship along with education. The three key areas provide a holistic overview of gender inequalities affect many facets of life with education being one of these. The report is fascinating and it provides a wealth of information on the issues affecting gender in education, along with proposals made by the OECD to policy makers to overcome them. The key findings will no doubt be familiar to many, such as the fact that boys are more likely to drop out of secondary education, which results in young women becoming increasingly better educated than young men in many OECD countries. It has also been well documented that:

The report argues that a major explanatory factor in these gender disparities is due to differences in attitudes. In order to address these disparities they outline key policy messages for governments to note such as getting “girls more interested in mathematics and science and boys more interested in reading in OECD countries, for example, by removing the gender bias in curricula and raising awareness of the likely consequences of male and female choices of fields of study in their careers and earnings”. They also suggest the use of apprenticeships to encourage women who have completed their science technology and mathematics (STEM) studies to work in scientific fields. Focusing on the role of educational aspirations which are formed in early life, the report recommends that more attention should be devoted to changing gender stereotypes and attitudes at a young age. It outlines how gender stereotyping takes place in subtle ways at home, in schools, and in society and the messages children and young people form when:

Although these points relate to what happens at the school, the report recognises the fact that attitudes are also crucially determined by what happens at home. This highlights the important fact that whatever teachers do in school they also have to consider how wider societal and family issues can affect outcomes in schools and any strategy to address these gender disparities should also focus on changing attitudes within the context of what goes on at home. Due to the nature of this posting I have only focused on a few issues highlighted in the report. For those of you wishing to read the full report it is available here. “To reap the highest economic and social return on education investment, therefore, it is important to find out just why there are gender differences in attitudes towards reading and mathematics, then to discover ways to reverse the imbalance.” Boys Reading

The OECD report focused on many issues affecting gender inequalities in education across the world. Moving closer to home the issue of boy’s reading in particular persistently remains an area of priority for most schools in England and the UK. The All Party Parliamentary Literacy Group Boys' Reading Commission working jointly with the National Literacy Trust found that ”three out of four (76%) UK schools are concerned about boys’ underachievement in reading despite no Government strategy to address the issue”. The commission published a report in July 2012 this year. In it they reveal that the “reading gender gap” is widening and says action needs to be taken in homes, schools and communities. The reading commission report provides a comprehensive overview of the issues, with evidence coming from three sources, including a survey of young people themselves. What will be particularly useful to schools and colleagues interested in closing the gender gaps in reading is that it also provides plenty of practical solutions of how boy’s literacy has been successfully supported by schools, thereby providing those of you wishing to address these issues with practical strategies of “what works” to implement in your own schools or classroom contexts. Links to the National Literacy Trust page on the Boy’s Reading Commission, which includes the report along with other relevant papers are available here. Please note that any of the views expressed above are mine alone and not necessarily those of the OECD or The National Literacy Trust. Equitable Education is available to provide specialist consultancy to schools in closing the gender gaps in education. |

Equitable EducationEquitable Education's blog keeps you updated with the latest news and developments in closing the gaps in education. We regularly share best practice materials and case studies of proven strategies to close the education gaps, along with the latest research from the UK and internationally. Archives

July 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed