This article has been republished from LeftCentral. It is also available to read on IPP

The pupil premium grant (PPG) is a flagship government scheme for schools. Next week it will be praised and celebrated at the 2013 pupil premium awards ceremony organised in partnership with the Department for Education (DfE).

An independent panel of experts has judged which schools have best used the PPG to make a real difference to the attainment of disadvantaged pupils.

However, almost two-thirds of the 48 schools that have been named as regional winners or commended for the awards ceremony have so far failed to comply fully with regulations relating to accountability. Also, about four-fifths of them appear to have ignored or misunderstood the regulations concerning accountability in the Equality Act 2010.

‘Take it and use it as you think fit. But …’

‘Take it, said Nick Clegg in 2011 when introducing the new grant to headteachers, ‘and use it as you see fit.’ He added a stern warning: ‘But know that you will be held accountable for what you achieve.’ The basic principle he was expressing – local freedom combined with public accountability – is central in the coalition government’s public discourse across a wide range of public policy.

In the case of the PPG, there are three main ways in which school leaders are held accountable for the decisions they make: a) through the performance tables which show the performance of disadvantaged pupils compared with their peers; b) through the Ofsted inspection framework, under which inspectors focus on the attainment of various pupil groups, including in particular those which attract the pupil premium; and c) the requirement to publish online information about the pupil premium for parents and others.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has noted with approval that the UK government requires schools to report to parents on how they have used additional money to close gaps in attainment connected with poverty and economic disadvantage.

How schools present the information in their online statement for parents is a matter for each school to decide for itself. There is certain minimum key information, however, which must by law be included on a school’s website. The amended school information regulations relating to this came into force in September 2012. Yet, as of June 2013, it appears that only a third of schools in receipt of the grant are fully complying with it.

Background

Monies previously allocated to other priorities have been redirected since 2010 towards children from low-income households, defined for the purposes of allocating the grant as those who are eligible for free school meals, or who have been eligible at any time in the last six years, and whose parents or carers have registered for free meals (though they may not have actually claimed them). Schools also receive funding for children who have been looked after continuously for more than six months, and for children of service personnel.

In the last financial year the grant was £623 per pupil. Since April 2013 it has been £900 per pupil. For children of service personnel it is £300. The grant does not have to be spent only on pupils who are eligible for free school meals. Its use must, however, be directed towards reducing or closing gaps in attainment connected with poverty and economic disadvantage. The total annual funding will be £2.5 billion by 2015. In his spending review announcement on 26 June 2013 Chancellor George Osborne pledged that the grant will continue in real terms – ‘so every poor child will have more cash spent on their future than ever before’.

In order that schools can be accountable to parents and others, they are required to publish on their website 1) their PPG allocation in respect of the current academic year, 2) details of how it is intended the allocation will be spent, 3) details of how the previous academic year’s allocation was spent, and 4) the impact of this expenditure on the educational attainment of pupils at the school in respect of whom the grant funding was allocated.

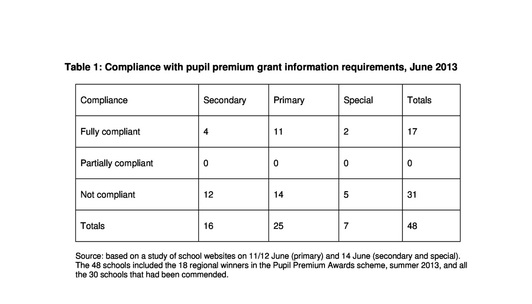

Study of 48 shortlisted schools

In June 2013 a study was made of the websites of the 48 schools –16 secondary, 25 primary, 7 special – that are regional winners or commended in the pupil premium awards scheme. Schools were judged in this study to be fully compliant with the statutory school information regulations if they had published all four of the required pieces of information; partially compliant if they had published at least three; and non-compliant of they had published no more than two, or had published nothing at all. Schools applied for the award on the basis of criteria that did not mention the requirement to publish information for parents.

The picture relating to the 48 schools shortlisted in the PPG awards is shown in Table 1 below.

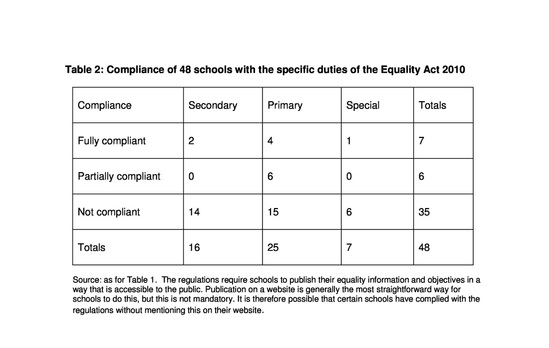

Principles of transparency and accountability determine not only how the pupil premium grant operates but also how public bodies are required to show due regard for the aims of the Equality Act. Under the Act’s specific duties, schools must a) publish information that demonstrates adequately an awareness of the diversity of the school population and how have had due regard for the aims of the Act, and b) prepare and publish at least one specific and measurable equality objective. To count as specific, an objective should state the outcome that the school aims to achieve. To count as measurable, the desired outcome must be quantifiable so that parents and the community can assess whether the school has been successful.

In order to determine their compliance with the accountability rules in the Equality Act, a study was made in June 2013 of the websites of the 48 schools featured in the pupil premium awards scheme. A school was judged to be fully compliant if it had published relevant information and at least one specific and measurable equality objective. It was judged to be partially compliant if it had published either equality information or measurable equality objectives, but not both, or if it was clearly aware of the duties even if it did not appear to have understood them. It was found that almost three-quarters of the schools shortlisted for the pupil premium awards (35 out of 48) failed to comply at all with the requirement to publish equality information and objectives. Less than one in six of them complied fully.

The overall picture is shown in Table 2.

The 48 schools whose websites were studied for this article are probably all making good use of the pupil premium grant, and the judges who selected them for special praise have made good decisions. It is surely surprising, however, that so many have not complied with regulations relating to accountability.

The principal reasons for non-compliance appear to lie in the failure of the government to provide adequate advice, guidance, challenge and support. Most of the schools which are non-compliant are probably unaware of the regulations and requirements, for the government has been generally light-touch in its publicity about them. Prior to 2010 schools would have received advice and support in relation to a project such as the pupil premium grant from their local authority. There would have been training and professional development opportunities, exchange of information about relevant research findings, and – crucially – much collaboration and joint reflection within local clusters and families of schools. Local networking along such lines is now much more problematic. It continues, however, to be an urgent necessity, and is a matter which requires the government’s attention.

Guidance, research and commentaries on the pupil premium grant have recently been published by, amongst others, the Sutton Trust, the Institute for Public Policy Research, the Department for Education and the Young Foundation. These reviews are much more substantial than the small-scale survey reported in this article. Their recurring conclusion, however, is that schools need more advice, training and challenge than they have so far received. Understandably and rightly the government does not wish to micro-manage what happens in schools. It nevertheless has a responsibility to ensure that good practice is widely shared. With the declining capacity and influence of local authorities, this responsibility is of urgent importance.

At the same time, the government needs to lead consideration of the links, connections and similarities between economic inequality and other forms of inequality, particularly those which are highlighted in the Equality Act. Each pupil stands at the intersection of several different strands of equality and inequality. For example, every child from a low-income household not only has a socio-economic location affected by poverty but also is a boy or a girl and has an identity in terms of ethnicity; many have special educational needs amounting to a disability; many have a religious identity which is important to them; all have a sexual identity. Some of a child’s educational needs cannot be appropriately met without reference to distinctive aspects of their experience, identity and reality – they are not ‘all the same’. One universal size does not fit them all.

Schools should therefore be encouraged both to explore intersectionality in their use of the premium grant and to pay due regard to economic disadvantage in their responses to the Equality Act. This is especially crucial in view of the fact that low income frequently intersects with the issues named in the Equality Act, particularly in relation to ethnicity, religion and disability. Overall, about 18 per cent of all young people are eligible for free school meals and therefore for the pupil premium grant. But for white pupils the proportion is slightly smaller, 16 per cent, whilst for certain others it is considerably higher. For children with special educational needs it is twice as high as for other children.

‘It is unacceptable,’ said the coalition government when it came to power in 2010, ‘for educational attainment to be affected by gender, disability, race, social class, sexual orientation or any other factor unrelated to ability. Every child deserves a good education and every child should achieve high standards. It is a unique sadness of our times that we have one of the most stratified and segregated school systems in the world …’ Such ideals and concerns sound like empty rhetoric if schools do not comply with rules of accountability.

Bill Bolloten tweets at @SchoolEquality and Robin Richardson at @Instedconsult.

There is further information at www.insted.co.uk (Robin Richardson).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed