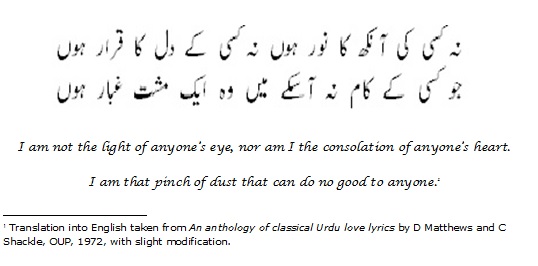

A few weeks ago, several of my colleagues @DiLeed @catharineEAL, @FranNantongwe, @chrisp09, @amdindependent, Dianne Excell and I had the opportunity to meet with Sean Harford, Ofsted’s National Director of Schools and Mark Sims, HMI, Lead for EAL and ESOL. On the day of our meeting the weather was glorious, so I decided to walk from King’s Cross to Aviation House where Ofsted is based as it would give me a chance to reminisce about my student days of living and studying in WC1 whilst I had been at SOAS. I’m glad I did because I had two encounters on my journey that made me think of the everyday diversity in London and how very different this was compared to Yorkshire where I live and work. Article published in Race Equality Teaching vol 23 no 2This couplet was written by the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. It is from a widely acclaimed ghazal[i] when he was exiled in Burma by the British after the 1857 Indian Rebellion (or Mutiny, depending on your perspective). His death in 1862 brought to an end the hugely successful Mughal dynasty established by his ancestor Babar in 1526. This article suggests that the government’s failure to collect, analyse and publish relevant information, as required by the specific duties of the 2010 Equality Act in modern Britain, implies that it sees the Equality Act as, in the words of Bahadur Shah Zafar, no more than ‘a speck of dust that can do no good to anyone’. In particular the article considers the lack of information about intersectionality and the lack of information about differences between regions and local authorities. The article refers mainly to race equality, but touches also on issues of gender and special educational needs.

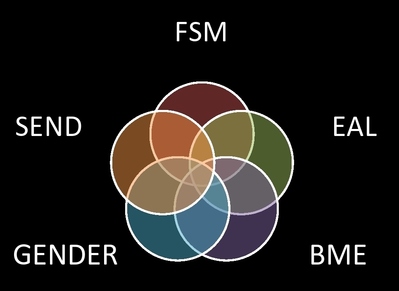

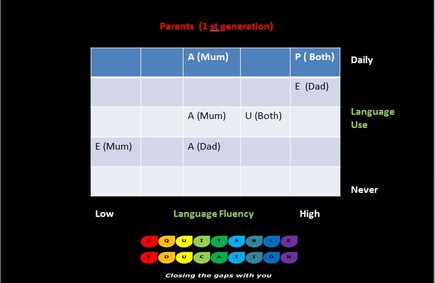

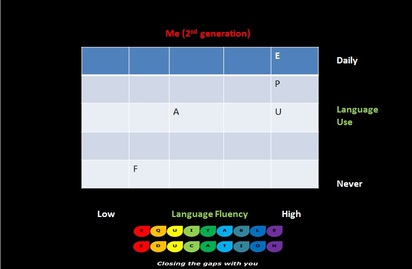

[i] A ghazal is a short love poem in which the two halves of the first couplet and the second line of the remaining couplets rhyme. 'One day' - Around the world in 24 hours, written by Suma Din and illustrated by Christiane Engel14/3/2014  I recently came across a beautifully written book focusing on the lives of 15 children going about their daily lives across the world, over a period of 24 hours. This book is great for introducing the concept of time zones in an engaging manner and is perfectly pitched at children in upper Key Stage 2. Readers are introduced to 15 ordinary yet fascinating children. By following what they do over a period of 24 hours, they get glimpses into their lives, families and everyday interactions, so much so that by the end of the book the reader is left wanting to know more about each character and a sense of disappointment that the book has finished prevails. Perhaps, the author Suma Din will write a follow up book developing these characters further.  Over the last few years there has been much emphasis placed on closing the socio-economic gaps in attainment between pupils who are eligible for free school meals and hence receive additional support through the Pupil Premium Grant and those who do not. This is a laudable policy ambition and is worthy of concentrated effort by all of us involved in educating children and young people. However, as with anything, the issues surrounding the closing of the attainment gaps are much more complex than just socio-economic deprivation. In his ground breaking report for Ofsted in 2000 entitled ‘Educational inequality: mapping race, class and gender. A synthesis of research evidence’ Professor David Gillborn showed how these three characteristics impacted on outcomes for different groups of pupils. I was recently asked to give a talk on ‘Being Bilingual’. I was privileged to present my talk alongside two fellow colleagues who are also bilingual and it was intriguing to hear the similarities and differences of how we used the linguistic repertoire at our disposal but within very different contexts. I shared my own experiences of bilingualism within the family by using a grid produced by Professor Francois Grosjean to show how language use and language fluency can vary across generations. In Professor Grosjean’s grid language use is presented along the vertical axis (from never used at the bottom all the way to daily use at the top) and language fluency is on the horizontal axis (from low fluency on the left to high fluency on the right. I started by sharing information on the language use and fluency of my parents. This is shown in the grid below with E= English, P =Panjabi (mother tongue), U=Urdu, which is used as a Lingua Franca in the Indian sub-continent and A= Arabic, often used for religious purposes. The use of language and fluency is, I believe, quite typical of many first generation members of the community who migrate to a new country, irrespective of actual languages and was certainly quite common amongst my parent’s generation who came to live and work in England in the 1960’s. As you can see from the grid it also shows quite interesting differences between male and females. Moving on to my generation and how we, meaning my siblings and I, use language is shown in the grid below. You will see the introduction of a new language, in this case F=French as we learned French as a MFL in school but also the level of proficiency in English and its use has overtaken the use of our mother tongue, particularly within the public domain with the first languages, although still frequently used, being firmly relegated to the private domain. What is less typical than many of our peers is the fact that we were able to main a high level of proficiency in our mother tongue Panjabi and Urdu, which in my case was because I had the very unusual and quite untypical opportunity to study both languages to a high level of proficiency at University. This meant I was able to develop high levels of literacy skills in these languages and a deep interest in its literature too. Sadly, many of our peers whilst maintaining high levels of spoken and listening comprehension skills in both Panjabi and Urdu more often than not, did not have the opportunity to learn to read and write in these languages, unless there was a supplementary school nearby as it was never an activity offered as part of mainstream education. Personally, I feel this is a very sad state of affairs whereby, by the second generation, the demise in the use of these languages is accelerated, as English quickly overtakes all other languages in both value and importance. Dr Dina Mehmedbogvic of the Institute of Education powerfully and poignantly articulates the start of language loss in her book entitled ‘Who wants the language of immigrants, Miss?'. At this point, second generation bilingual children living in England, at a very young age quickly become aware that their linguistic heritage is not of the same status as English. In many cases this can led to children and young people, instead of seeing these languages as a valuable asset for both personal and future career prospects, begin to resent and in some cases deny that the can speak these languages in public spheres of life. At this stage some children and young people may still be able to comprehend the languages of their families but either through choice or the situation they find themselves in, are unable reproduce the languages effectively to communicate. Therefore, by the third generation, most of the languages that should have been passed on a gift, as part of their heritage, are almost lost and the language of the host country has overwhelmingly replaced any others in all domains of language use. Once the language of their heritage is lost it is very difficult to replace and ironically in this growing globalised world it is these very languages that are likely to become useful for economic reasons in the future.

The lack of a languages strategy for schools has been lamented by many and recently with the introduction of the EBacc languages are being given a higher profile and gradually the numbers of pupils studying languages is increasing. Sadly, though much of these positive moves still focus on Modern Foreign Languages and creates a false dichotomy between MFL and so called ‘Community Languages’ many of whom ironically are world languages and have many millions of speakers across the globe! This lack of joined up ‘Languages Strategy’ for education continues presently yet it is a missed opportunity for successive policy makers as it to fail to tap into and embrace the many positive aspects of bilingualism. This month’s British Council Report ‘The Languages for the Future’ report identifies a range of languages [1], including many spoken by migrant communities as being essential to the UK over the next 20 years. These languages were chosen based on economic, geopolitical, cultural and educational factors including the needs of UK businesses, the UK’s overseas trade targets, diplomatic and security priorities, and prevalence on the internet. But, according to an online YouGov poll of more than 4000 UK adults commissioned by the British Council as part of the report, three quarters (75%) are unable to speak any of these languages well enough to hold a conversation. It certainly seems time for policy makers to pay heed to the latest research and consider how it can support the learning of languages amongst its population, including the maintenance of languages already spoken within communities. [1] Spanish, Arabic, French, Mandarin Chinese, German, Portuguese, Italian, Russian, Turkish and Japanese  Equitable Education is pleased to announce that it is an active supporter of the 1000 words campaign developed by Speak to the Future. This extremely worthwhile campaign has arisen out of the findings of the excellent British Academy called ‘Languages: the State of the Nation’. Readers of this blog will recall that the report highlighted the following key findings: o The UK is suffering from a growing deficit in foreign language skills at a time when global demand for language skills is expanding o The range and nature of languages being taught is insufficient to meet current and future demand o Language skills are needed at all levels in the workforce, not simply by an internationally-mobile elite. The 1000 words campaign is designed to encourage everyone to learn and use languages because they are important for everyone not just a select few. This is equally relevant whether you are learning a foreign language or English as an additional language or indeed part of a bilingual or multilingual family where different languages are routinely used in the home and community. Equitable Education has a firm commitment to encouraging partners it works with, especially schools and educational organisations, to value, nurture and develop a lifelong love of languages because of the considerable benefits that accrue to individuals and society at large. We feel that a campaign such as the 1000 words campaign will raise the profile of the importance of languages and encourage educational organisations to take an active part so that our citizens are more at ease in learning languages and can at least converse at a basic level in another language. Here are a few ways in which schools and universities can get actively involved in the 1000 words campaign. These are only suggestions and of course schools are free to choose and adapt these activities to fit their needs and communities. Primary Schools

Secondary Schools

For further ideas and resources, go to http://www.allanguages.org.uk/news/features/making_the_case_why_students_need_to_study_languages Universities, or university departments

For further ideas and resources, go to www.routesintolanguages.ac.uk, www.llas.ac.uk or www.ucml.ac.uk Supplementary schools

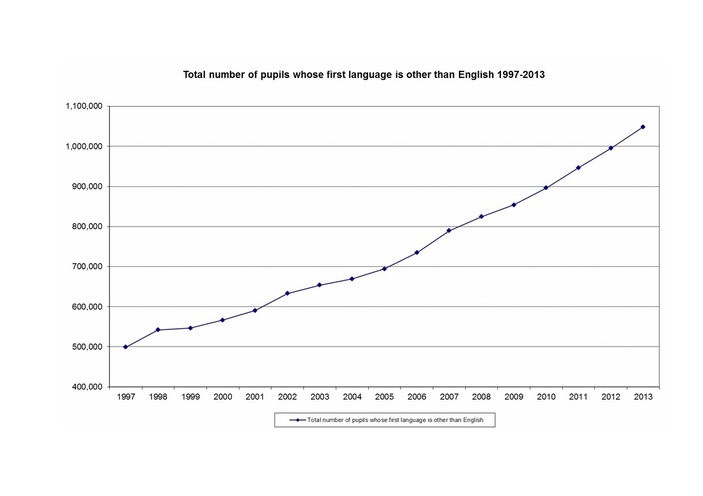

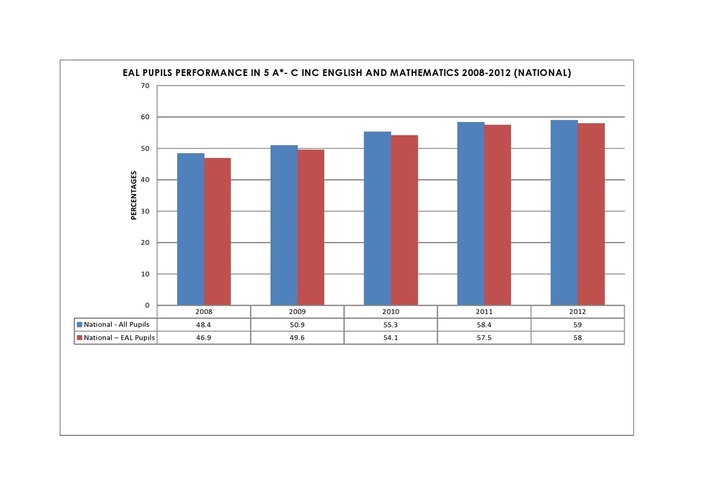

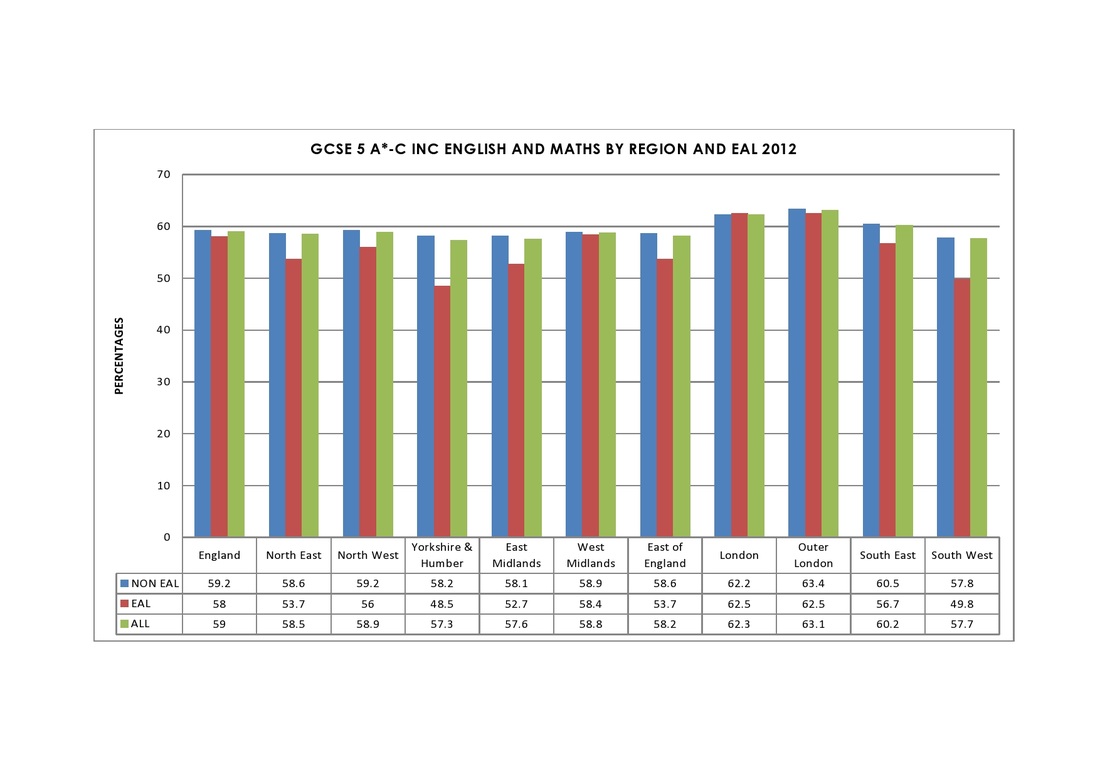

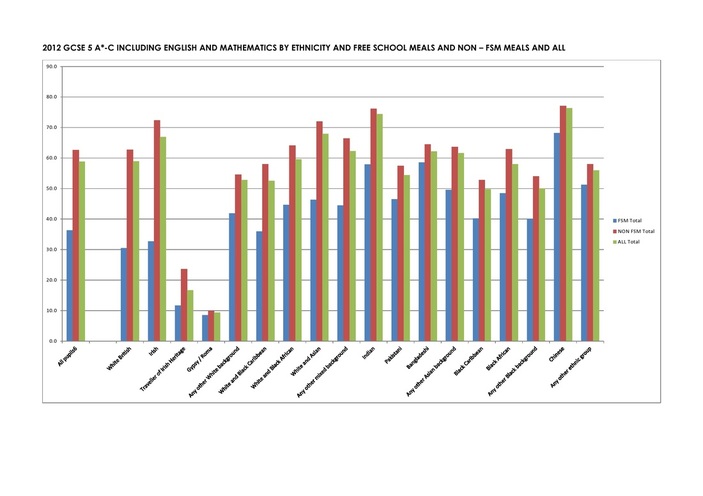

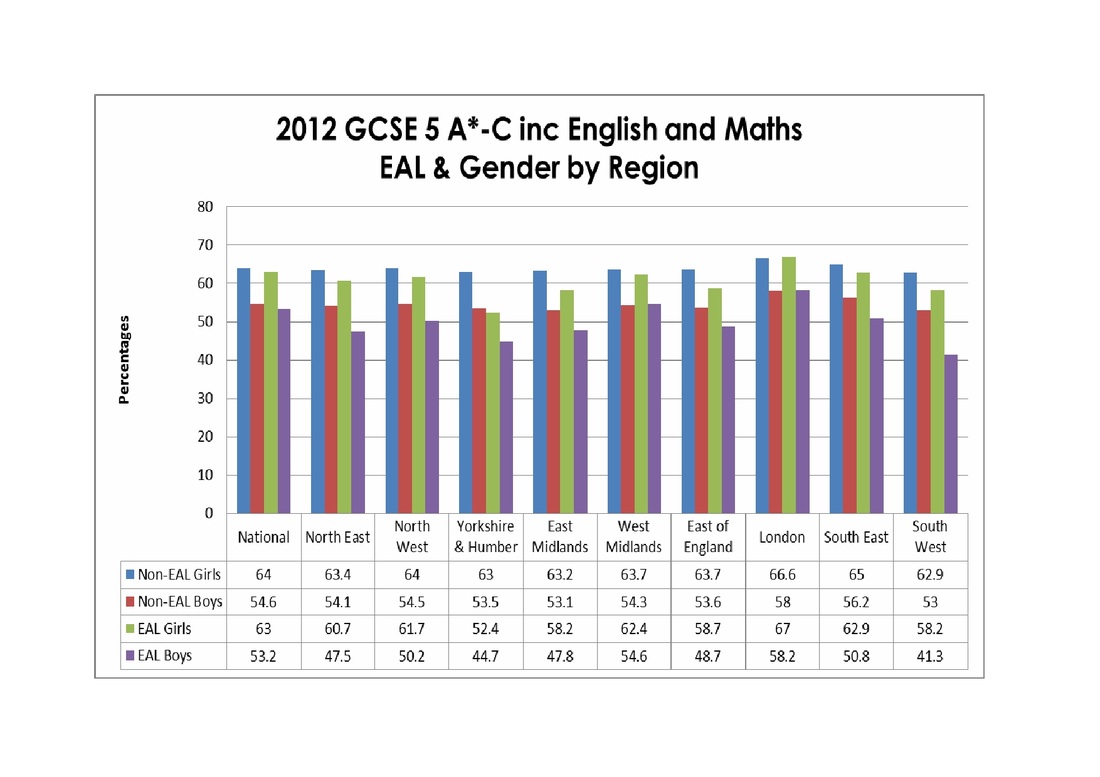

Further updates on ways in which we and our educational partners are engaging with the 1000 words campaign will be highlighted in future blog postings. In the meantime, if you would like support in developing activities to promote a love of learning languages don’t hesitate to get in touch with us on [email protected] I am currently writing a paper on the present situation with regards to EAL pupils in England, which will cover the following: · Provide an overview of the official approaches to EAL over the past 30 years or so, · Briefly outline associated research into EAL pupil’s both national and international, · The current attainment of EAL pupils in England · Highlight examples of best practice in schools across regions and LA · Stress the urgent need for a more nuanced and focused strategy for pupils for whom English is an additional language at a national level · Outline recommendations The intended purpose of the paper is to encourage reflection, debate and forward strategy at a time when the current education system is undergoing considerable change leading to both potential opportunities and considerable challenges. In such situations there is the strong likelihood that the needs of some groups of pupils are missed especially when the spotlight is shifted to other groups who are deemed more worthy or more in vogue, leading to unnecessary binary approaches to raising attainment. This blog posting summarises some of the key headlines of this paper. The DfE recently released the latest statistics on the number of pupils for whom English is an additional language (EAL). These figures show that there are now over 1 million pupils whose first language is other than English, with the percentages in primary standing at 18.1% compared to 17.5% last year and 13.6% for secondary showing a 0.7% increase on last year. These annual increases show the growing number of EAL pupils in schools in England and are illustrated in the graph below: The trend shows that the numbers of EAL pupils are likely to continue to increase. As a result teaching EAL pupils is now an issue for all schools at a time when many professionals within education report that they do not feel well trained in addressing pupil’s EAL needs (read my earlier blog on EAL and ITE &CPD needs here). The attainment results over the past few years have shown that outcomes for EAL pupils have improved significantly leading to the attainment gaps virtually closing at a national level in terms of the gold standard 5 A*-C including English & Maths grades at GCSE. The graph below shows how the attainment gap at a national level has virtually disappeared over the past five years. These results for the last five years show a vast improvement compared to previously when most EAL pupils were significantly languishing behind their peers. Just a generation ago it was routine for bilingual pupils to be sent to separate language centres to learn English before being admitted to schools. This gradually changed to EAL pupils being sent to language centres within schools and being taught separately until it was felt that they would be able to cope with the mainstream curriculum of their peers. If EAL pupils were extremely lucky then they may have made it directly into the mainstream, escaping the need to receive an alternative curriculum but were often left to sink or swim, without any support or appreciation of their EAL needs. Nowadays these practices would be deemed abhorrent and totally going against well- known research of how bilingual pupils acquire and learn languages. Although these incidents happened approximately 25 – 30 years ago and illustrate the distance that has been travelled so far, they also highlight the journey which still needs to be travelled, until we get to a situation whereby all teachers have the understanding, knowledge and skills to address the needs of EAL pupils within the mainstream context and deliver high quality teaching and learning to enable all EAL pupils attain national expectations. It therefore seems appropriate to briefly take stock of where we are now in relation to meeting the needs of pupils for whom English is an additional language in England and look at the potential of where we should be in the very near future. I have listed a few key headlines below: · At national levels gaps are closing as the graph above shows. These results also mean that some of the powerful negative myths that have perpetuated in relation to bilingual pupils and their attainment are being exploded, resulting in the fact that bilingual pupils can and should achieve academic excellence as a matter of course. · Better outcomes in attainment mean that more EAL pupils have the potential to accrue the benefits of higher education. This should contribute to better opportunities for gainful employment and improved life chances resulting in economic, social and health benefits for many more community members in the future. · Generally most minority ethnic pupils have higher proportions of pupils for whom English is an additional language, with the exception of Black Caribbean pupils. This means that the positive aspects of being bilingual such as those outlined by many academics such as Jim Cummins, Colin Baker, Stephen Krashen, Tove Skutnabb- Kangas and more recently Ellen Bialystok can be used as a lever to support the learning of minority ethnic pupils currently not performing in line with their peers nationally. · Indian and Chinese pupils have been performing much higher than their peers for many years now. Both of these groups have high proportions of bilingual speakers, with over 80% of Indian pupils and 73% of Chinese pupils speaking English as an additional language.[1] More recently the performance of Bangladeshi pupils nationally has also accelerated with impressive performances. Previous reasons cited for Indian and Chinese pupils academic success have been attributed to lower rates of free school meal eligibility in these groups at 12% for Indian pupils and 14% for Chinese pupils. However, the performance Bangladeshi pupils, with one of the highest free school eligibility figures at 52%, add to the growing body of evidence which shows that pupils eligible for free school meals also perform very highly, setting the precedence for others to follow. · There is growing evidence which is exploding many of the myths surrounding EAL pupils. An example of this of is the recent research undertaken by Professor Sandra Mc Nally et al from the London School of Economics, Centre for the Economics of Education. Their research shows that EAL pupils do not negatively impact on standards for non-EAL pupils. For further details read my previous blog here) HOWEVER, despite the seemingly positive picture emerging at a national level, there remain significant CHALLENGES · There are extreme variations in EAL pupil’s attainment by region which the national figures mask. Nationally 58% of EAL pupils in England achieved 5 A*- C in English in Mathematics in 2012. However, EAL pupils in London performed 4.5 percentage points higher at 62.5% compared to those in Yorkshire & Humber who performed nearly 10 percentage points lower at only 48.5%. The graph below shows the regional variations in EAL pupils attainment 5 A*-C in English and Maths in 2012 [1] Figures cited are from ‘Ethnicity and Educational Achievement in Compulsory Schooling’ by Christian Dustmann, Stephen Machin and Uta Schonberg in The Economic Journal 2010. · EAL pupil’s performance within particular LA’s shows further huge variations in attainment with only 32.7% of EAL pupils achieving the gold standard at GCSE in Hereford LA compared to 82.8% of their peers in Kensington and Chelsea or 82% in Sutton. These huge disparities which continue to exist in different LA’s show the necessity to look beyond the national picture. Presently, where you live in England seems to exert a great influence of your educational outcomes which is morally unacceptable. · The success in closing of the gap of EAL pupils nationally can be attributed to a large extent to the higher performance of EAL pupils in London and West Midlands, where there are larger concentrations of EAL pupils, with improvements in London largely due to the success of ‘The London Challenge’. Amongst the various strategies which have been cited in accounting for the success of the London Challenge, the Pan EAL London EAL Strategy is worth highlighting for particular attention. The Pan EAL London Strategy enabled LA’s to receive additional funding to support effective teams to provide support for EAL pupils and to spread this expertise across London. The effectiveness of this work has been highlighted by M Hutchings and A Mansaray in ‘A review of the impact of the London Challenge (2003-8) and the City Challenge (2008-11)’ submitted as evidence to Ofsted’s ‘Access and Achievement’ Review a few months ago. · There are further variations in EAL pupil’s performance when looking at other characteristics such as ethnicity, socio-economic background and gender. Socio-economic gaps are more pronounced for White British groups compared to most ethnic minority groups. For some minority ethnic groups this is because non – free school meal pupils are less likely to come from families with higher socio-economic and professional backgrounds so the differences are less marked. Since national data is not available by ethnicity and EAL, ethnicity data can provide a useful indicator of performance, bearing in mind the intersections of ethnicity and EAL. The differences in performance by FSM eligibility and ethnicity are shown in the graph below: · Bangladeshi pupil’s performance nationally is skewed by the fact that over half of all Bangladeshi pupils live in London, with about a third located in Tower Hamlets alone. Tower Hamlets is one of the success stories and had an impressive 67.8 % of EAL pupils attain 5 A*- C including English and Mathematics in 2012 which is nearly 10 % above the national average. · There are considerable differences in attainment when looking at key stages with outcomes much lower for all minority ethnic and EAL pupils at the start of schooling and even at the end of primary for most groups compared to secondary where most of the gains for EAL pupils are made. This is well documented by researchers.[1] This means the potential outcomes of EAL pupils could be accelerated further if the progress seen in secondary, particularly at KS 4 was replicated in primary. · Gender differences also impact across various regions with EAL girls generally performing much higher than both non-EAL and EAL boys with the exception of the Yorkshire & Humber region where EAL girls performed marginally better than EAL boys but lower than non – EAL girls and boys. The graph below shows how EAL and Gender characteristics lead to extremely differential outcomes across regions with EAL boys in the South West performing the lowest in 2012 leading to a gap of 16.9% compared to their peers in London. [1] ‘The Dynamics of School Attainment of England’s Ethnic Minorities’by Deborah Wilson, Simon Burgess and Adam Briggs CASE paper 2006, ‘A Comparative Analysis of Bangladeshi and Pakistani Educational Attainment in London Secondary Schools’ by Sunder Divya and Layli Uddin 2007, Drivers and Challenges in Raising the Achievement of Pupils from Bangladeshi, Somali and Turkish Backgrounds by Steve Strand et al 2010 and Figures cited are from ‘Ethnicity and Educational Achievement in Compulsory Schooling’ by Christian Dustmann, Stephen Machin and Uta Schonberg in The Economic Journal 2010. · The regional differences are further compounded when looking at the performance in LA’s e.g. only 30 % of EAL boys and 39.3 % of EAL girls in Blackpool LA achieved the gold standard at GCSE last year. This is a stark contrast to the 81.7 % of EAL boys and 84.3 % of EAL girls in Kensington & Chelsea who achieved this benchmark.

· Another consideration is in relation to the performance of EAL pupils in mainly white LA’s. The issues are complex and may be down to the arrival of newer communities or lack of strategy and expertise in supporting EAL pupils particularly when EAL pupils are dispersed across an LA and are considered to be relatively small. It seems that we in England are at the cusp of making sustained changes in ensuring better educational outcomes for our EAL pupils, many of whom until recently have been languishing behind their peers. Taking a long view there is much to be celebrated and built upon. However, considering the fact that it has taken us over 30 years to get to this stage, with the gains by no means sustained nationally for all key stages and certainly not across regions and LA’s it is imperative that the best practice that is evident is disseminated as a matter of urgency to so that the momentum continues to be built upon. Sadly, although the national results for EAL pupils are applauded there is little if any emphasis on meeting the needs of EAL pupils in other areas or indeed in using flagship policies such as the Pupil Premium to stress the interlinked relationships that exist for EAL pupils and other characteristics such as free school meal eligibility. A more focused and nuanced policy at a national level is required to ensure that the potential of all EAL pupils, irrespective of ethnicity, socio-economic backgrounds and gender is realised and the impact of where you live or which you school you go to does not result in a lottery in achieving better educational outcomes. The headlines are based on a detailed paper which is currently being written by Sameena Choudry on EAL pupils in England and the need for a nuanced strategy to close the gaps. For many centuries Roma community members have been and continue to be subjected to unfair treatment and vilified in many countries in Europe. This often means that community members are forced to live on the margins of society and are treated like second class citizens event though their families have been settled there for many centuries. One of the saddest aspects of this that many Roma children have been forced to attend separate schools from the host communities. Even more disturbing is the fact that a high percentage of Roma pupils are routinely placed in special schools in Eastern Europe when they should be going to ordinary schools.

Many international organisations and countries including the Court of Human Rights have criticised the abhorrent practice but despite these challenges to the Czech Republic and Slovakia, Roma pupils are more than 27 more times likely to be placed in special schools [i] As a result of the harsh discrimination which members of the Roma communities suffer in Europe some have migrated to the United Kingdom over the last few years. It is known at Local Authority level that many Roma pupils currently underachieve. When looking at national disaggregated performance data Roma pupils are categorised along with Gypsy and Traveller pupils and it can be difficult to see the performance of Roam pupils as a separate group. However, the overaraching groups of GRT is the lowest performing group in England at all key stages and although many of the wider issues affecting Gypsy and Traveller pupils are the same for Roma pupils there are also distinct differences too, such as the fact that 90% of Roma pupils also have English as an additional language needs. However, very little research has been conducted into the educational experiences and attainment of Roma pupils in England which remains a key area which needs to be explored further. There is however one excellent research report that was conducted in November 2011 called ‘From Segregation to Inclusion: Roma Pupils in the United Kingdom, A pilot research project. This excellent report provides a wealth of useful information and hopefully is the first of its kind to provide much needed information to inform practice and pedagogy to meet the needs of Roma pupils in schools so that they can achieve on a par with their peers. Colleagues working for Equality UK, the organisation conducting the research above interviewed 61 Czech or Slovak Roma students, along with 28 Roma parents and 25 school staff across eight locations - Leicester, Chatham, Rotherham, Wolverhampton, Southend on Sea, Peterborough, London, and Derby. The key findings of the field work and research are quite stark:

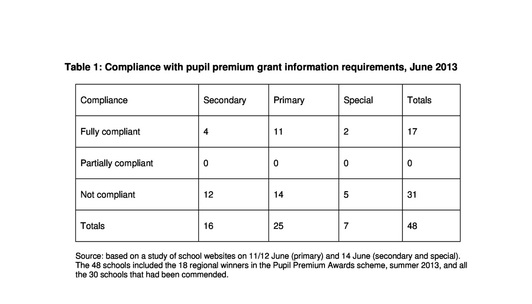

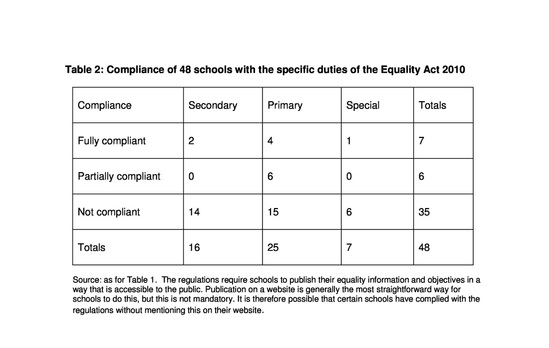

The report highlights a number of recommendations for both the international community to improve the educational systems for Roma pupils in Europe, as well as within the UK including the sharing of best practice which exists in LA and schools. Although the research sample is still relatively small it is the first of its kind and it provides detailed information gained as a result of the case studies undertaken with Roma pupils, their parents and staff. This insight into the views, experiences and future aspirations of Roma pupils with prove beneficial for teachers and staff working with schools and who wish to enhance their understanding of the educational needs of Roma pupils. For those interested in finding out more about how to respond to the educational needs of Roma pupils and develop best practice in their own schools or LA’s we shall be sharing the best practice in schools we know where they are leading the way in making a difference for Roma pupils. Future blogs will highlight what it is these successful schools are doing to achieve high educational outcomes for Roma pupils and ensuring an inclusive ethos which makes them feel safe, settled, secure and part of the whole school community. [i] Source Council of Europe, Report by Thomas Hammarberg,Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe,following his visit to theCzech Republic from 17 to 19 November 2010; CommDH (2011)3, 3 March 2011, availableonline:https://wcd.coe.int/wcd/ViewDoc.jsp?id=1754217,para 60 cited in From Segregation to Inclusion: Roma Pupils in the United Kingdom, A pilot research project. Bill Bolloten, Sameena Choudry and Robin Richardson This article has been republished from LeftCentral. It is also available to read on IPP The pupil premium grant (PPG) is a flagship government scheme for schools. Next week it will be praised and celebrated at the 2013 pupil premium awards ceremony organised in partnership with the Department for Education (DfE). An independent panel of experts has judged which schools have best used the PPG to make a real difference to the attainment of disadvantaged pupils. However, almost two-thirds of the 48 schools that have been named as regional winners or commended for the awards ceremony have so far failed to comply fully with regulations relating to accountability. Also, about four-fifths of them appear to have ignored or misunderstood the regulations concerning accountability in the Equality Act 2010. ‘Take it and use it as you think fit. But …’ ‘Take it, said Nick Clegg in 2011 when introducing the new grant to headteachers, ‘and use it as you see fit.’ He added a stern warning: ‘But know that you will be held accountable for what you achieve.’ The basic principle he was expressing – local freedom combined with public accountability – is central in the coalition government’s public discourse across a wide range of public policy. In the case of the PPG, there are three main ways in which school leaders are held accountable for the decisions they make: a) through the performance tables which show the performance of disadvantaged pupils compared with their peers; b) through the Ofsted inspection framework, under which inspectors focus on the attainment of various pupil groups, including in particular those which attract the pupil premium; and c) the requirement to publish online information about the pupil premium for parents and others. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has noted with approval that the UK government requires schools to report to parents on how they have used additional money to close gaps in attainment connected with poverty and economic disadvantage. How schools present the information in their online statement for parents is a matter for each school to decide for itself. There is certain minimum key information, however, which must by law be included on a school’s website. The amended school information regulations relating to this came into force in September 2012. Yet, as of June 2013, it appears that only a third of schools in receipt of the grant are fully complying with it. Background Monies previously allocated to other priorities have been redirected since 2010 towards children from low-income households, defined for the purposes of allocating the grant as those who are eligible for free school meals, or who have been eligible at any time in the last six years, and whose parents or carers have registered for free meals (though they may not have actually claimed them). Schools also receive funding for children who have been looked after continuously for more than six months, and for children of service personnel. In the last financial year the grant was £623 per pupil. Since April 2013 it has been £900 per pupil. For children of service personnel it is £300. The grant does not have to be spent only on pupils who are eligible for free school meals. Its use must, however, be directed towards reducing or closing gaps in attainment connected with poverty and economic disadvantage. The total annual funding will be £2.5 billion by 2015. In his spending review announcement on 26 June 2013 Chancellor George Osborne pledged that the grant will continue in real terms – ‘so every poor child will have more cash spent on their future than ever before’. In order that schools can be accountable to parents and others, they are required to publish on their website 1) their PPG allocation in respect of the current academic year, 2) details of how it is intended the allocation will be spent, 3) details of how the previous academic year’s allocation was spent, and 4) the impact of this expenditure on the educational attainment of pupils at the school in respect of whom the grant funding was allocated. Study of 48 shortlisted schools In June 2013 a study was made of the websites of the 48 schools –16 secondary, 25 primary, 7 special – that are regional winners or commended in the pupil premium awards scheme. Schools were judged in this study to be fully compliant with the statutory school information regulations if they had published all four of the required pieces of information; partially compliant if they had published at least three; and non-compliant of they had published no more than two, or had published nothing at all. Schools applied for the award on the basis of criteria that did not mention the requirement to publish information for parents. The picture relating to the 48 schools shortlisted in the PPG awards is shown in Table 1 below. The Equality Act 2010 Principles of transparency and accountability determine not only how the pupil premium grant operates but also how public bodies are required to show due regard for the aims of the Equality Act. Under the Act’s specific duties, schools must a) publish information that demonstrates adequately an awareness of the diversity of the school population and how have had due regard for the aims of the Act, and b) prepare and publish at least one specific and measurable equality objective. To count as specific, an objective should state the outcome that the school aims to achieve. To count as measurable, the desired outcome must be quantifiable so that parents and the community can assess whether the school has been successful. In order to determine their compliance with the accountability rules in the Equality Act, a study was made in June 2013 of the websites of the 48 schools featured in the pupil premium awards scheme. A school was judged to be fully compliant if it had published relevant information and at least one specific and measurable equality objective. It was judged to be partially compliant if it had published either equality information or measurable equality objectives, but not both, or if it was clearly aware of the duties even if it did not appear to have understood them. It was found that almost three-quarters of the schools shortlisted for the pupil premium awards (35 out of 48) failed to comply at all with the requirement to publish equality information and objectives. Less than one in six of them complied fully. The overall picture is shown in Table 2. Concluding notes

The 48 schools whose websites were studied for this article are probably all making good use of the pupil premium grant, and the judges who selected them for special praise have made good decisions. It is surely surprising, however, that so many have not complied with regulations relating to accountability. The principal reasons for non-compliance appear to lie in the failure of the government to provide adequate advice, guidance, challenge and support. Most of the schools which are non-compliant are probably unaware of the regulations and requirements, for the government has been generally light-touch in its publicity about them. Prior to 2010 schools would have received advice and support in relation to a project such as the pupil premium grant from their local authority. There would have been training and professional development opportunities, exchange of information about relevant research findings, and – crucially – much collaboration and joint reflection within local clusters and families of schools. Local networking along such lines is now much more problematic. It continues, however, to be an urgent necessity, and is a matter which requires the government’s attention. Guidance, research and commentaries on the pupil premium grant have recently been published by, amongst others, the Sutton Trust, the Institute for Public Policy Research, the Department for Education and the Young Foundation. These reviews are much more substantial than the small-scale survey reported in this article. Their recurring conclusion, however, is that schools need more advice, training and challenge than they have so far received. Understandably and rightly the government does not wish to micro-manage what happens in schools. It nevertheless has a responsibility to ensure that good practice is widely shared. With the declining capacity and influence of local authorities, this responsibility is of urgent importance. At the same time, the government needs to lead consideration of the links, connections and similarities between economic inequality and other forms of inequality, particularly those which are highlighted in the Equality Act. Each pupil stands at the intersection of several different strands of equality and inequality. For example, every child from a low-income household not only has a socio-economic location affected by poverty but also is a boy or a girl and has an identity in terms of ethnicity; many have special educational needs amounting to a disability; many have a religious identity which is important to them; all have a sexual identity. Some of a child’s educational needs cannot be appropriately met without reference to distinctive aspects of their experience, identity and reality – they are not ‘all the same’. One universal size does not fit them all. Schools should therefore be encouraged both to explore intersectionality in their use of the premium grant and to pay due regard to economic disadvantage in their responses to the Equality Act. This is especially crucial in view of the fact that low income frequently intersects with the issues named in the Equality Act, particularly in relation to ethnicity, religion and disability. Overall, about 18 per cent of all young people are eligible for free school meals and therefore for the pupil premium grant. But for white pupils the proportion is slightly smaller, 16 per cent, whilst for certain others it is considerably higher. For children with special educational needs it is twice as high as for other children. ‘It is unacceptable,’ said the coalition government when it came to power in 2010, ‘for educational attainment to be affected by gender, disability, race, social class, sexual orientation or any other factor unrelated to ability. Every child deserves a good education and every child should achieve high standards. It is a unique sadness of our times that we have one of the most stratified and segregated school systems in the world …’ Such ideals and concerns sound like empty rhetoric if schools do not comply with rules of accountability. Bill Bolloten tweets at @SchoolEquality and Robin Richardson at @Instedconsult. There is further information at www.insted.co.uk (Robin Richardson). |

Equitable EducationEquitable Education's blog keeps you updated with the latest news and developments in closing the gaps in education. We regularly share best practice materials and case studies of proven strategies to close the education gaps, along with the latest research from the UK and internationally. Archives

July 2015

Categories

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed