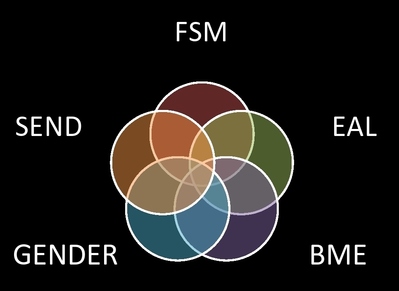

Over the last few years there has been much emphasis placed on closing the socio-economic gaps in attainment between pupils who are eligible for free school meals and hence receive additional support through the Pupil Premium Grant and those who do not. This is a laudable policy ambition and is worthy of concentrated effort by all of us involved in educating children and young people. However, as with anything, the issues surrounding the closing of the attainment gaps are much more complex than just socio-economic deprivation. In his ground breaking report for Ofsted in 2000 entitled ‘Educational inequality: mapping race, class and gender. A synthesis of research evidence’ Professor David Gillborn showed how these three characteristics impacted on outcomes for different groups of pupils.

3 Comments

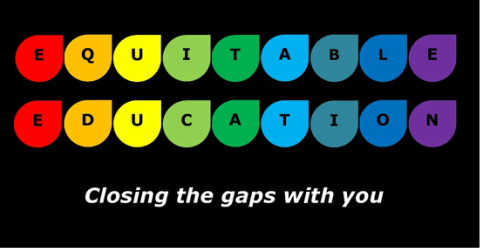

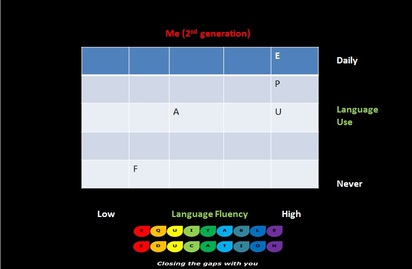

I was recently asked to give a talk on ‘Being Bilingual’. I was privileged to present my talk alongside two fellow colleagues who are also bilingual and it was intriguing to hear the similarities and differences of how we used the linguistic repertoire at our disposal but within very different contexts. I shared my own experiences of bilingualism within the family by using a grid produced by Professor Francois Grosjean to show how language use and language fluency can vary across generations. In Professor Grosjean’s grid language use is presented along the vertical axis (from never used at the bottom all the way to daily use at the top) and language fluency is on the horizontal axis (from low fluency on the left to high fluency on the right. I started by sharing information on the language use and fluency of my parents. This is shown in the grid below with E= English, P =Panjabi (mother tongue), U=Urdu, which is used as a Lingua Franca in the Indian sub-continent and A= Arabic, often used for religious purposes. The use of language and fluency is, I believe, quite typical of many first generation members of the community who migrate to a new country, irrespective of actual languages and was certainly quite common amongst my parent’s generation who came to live and work in England in the 1960’s. As you can see from the grid it also shows quite interesting differences between male and females. Moving on to my generation and how we, meaning my siblings and I, use language is shown in the grid below. You will see the introduction of a new language, in this case F=French as we learned French as a MFL in school but also the level of proficiency in English and its use has overtaken the use of our mother tongue, particularly within the public domain with the first languages, although still frequently used, being firmly relegated to the private domain. What is less typical than many of our peers is the fact that we were able to main a high level of proficiency in our mother tongue Panjabi and Urdu, which in my case was because I had the very unusual and quite untypical opportunity to study both languages to a high level of proficiency at University. This meant I was able to develop high levels of literacy skills in these languages and a deep interest in its literature too. Sadly, many of our peers whilst maintaining high levels of spoken and listening comprehension skills in both Panjabi and Urdu more often than not, did not have the opportunity to learn to read and write in these languages, unless there was a supplementary school nearby as it was never an activity offered as part of mainstream education. Personally, I feel this is a very sad state of affairs whereby, by the second generation, the demise in the use of these languages is accelerated, as English quickly overtakes all other languages in both value and importance. Dr Dina Mehmedbogvic of the Institute of Education powerfully and poignantly articulates the start of language loss in her book entitled ‘Who wants the language of immigrants, Miss?'. At this point, second generation bilingual children living in England, at a very young age quickly become aware that their linguistic heritage is not of the same status as English. In many cases this can led to children and young people, instead of seeing these languages as a valuable asset for both personal and future career prospects, begin to resent and in some cases deny that the can speak these languages in public spheres of life. At this stage some children and young people may still be able to comprehend the languages of their families but either through choice or the situation they find themselves in, are unable reproduce the languages effectively to communicate. Therefore, by the third generation, most of the languages that should have been passed on a gift, as part of their heritage, are almost lost and the language of the host country has overwhelmingly replaced any others in all domains of language use. Once the language of their heritage is lost it is very difficult to replace and ironically in this growing globalised world it is these very languages that are likely to become useful for economic reasons in the future.

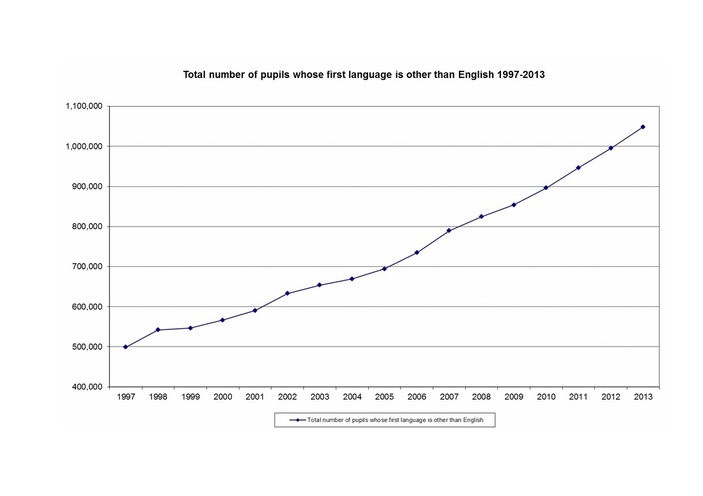

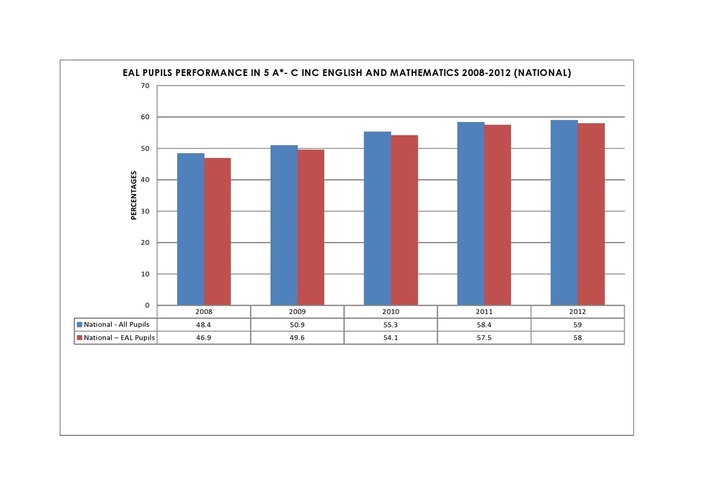

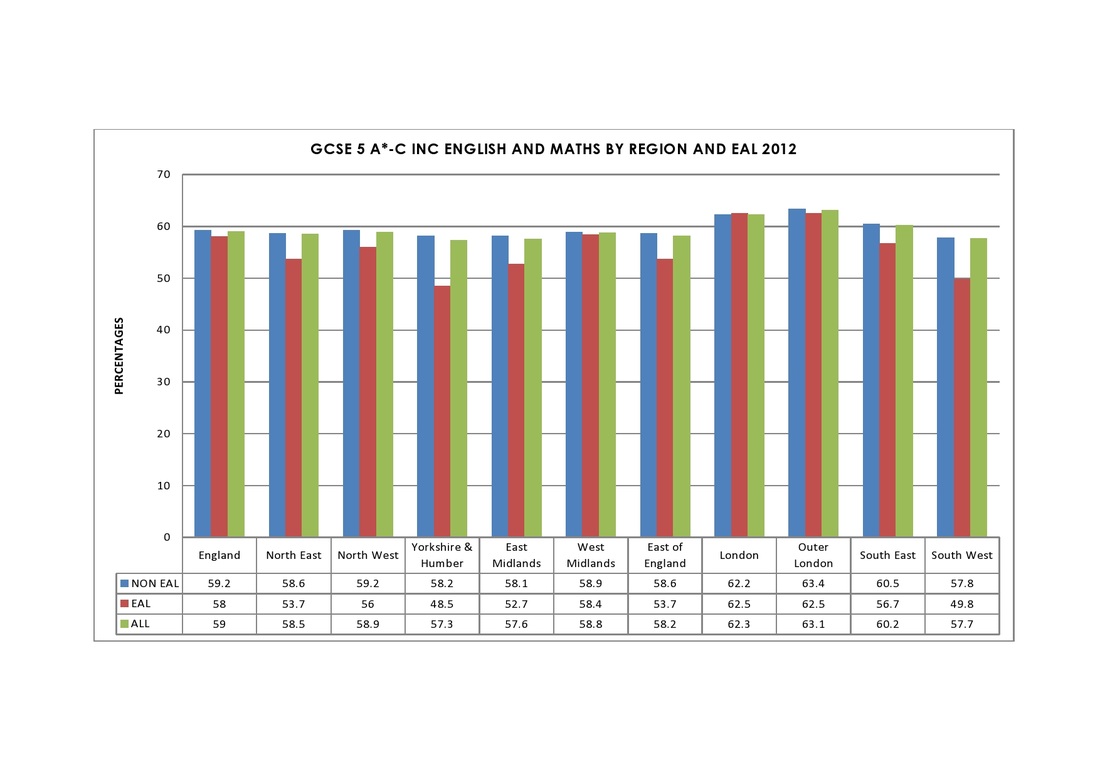

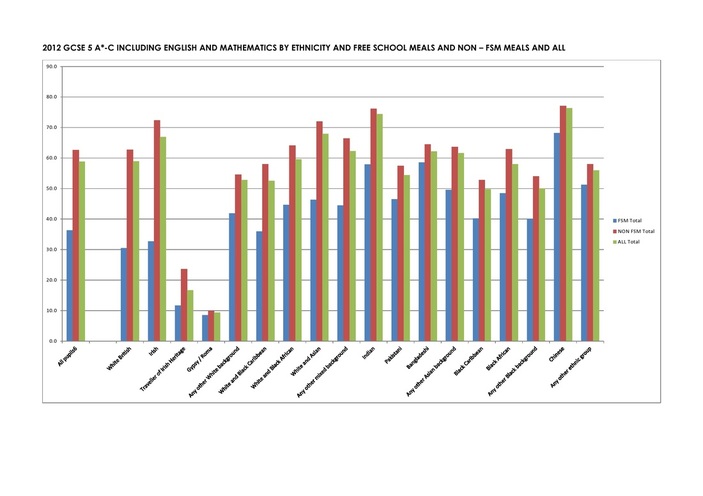

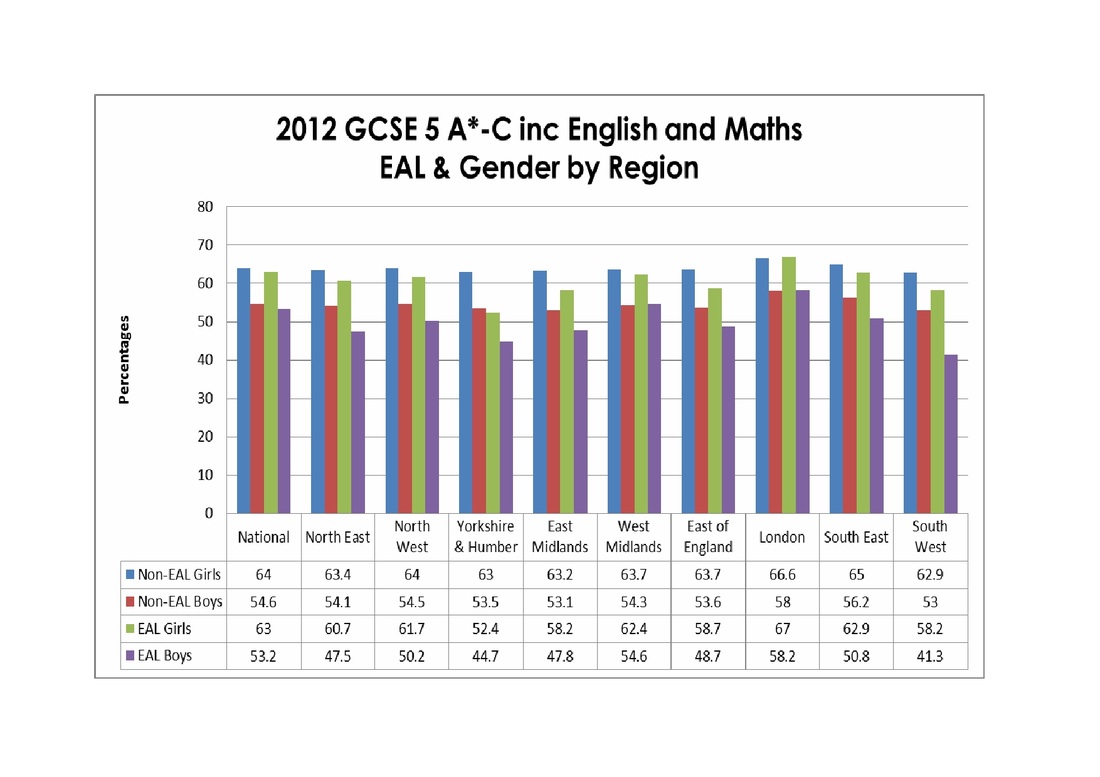

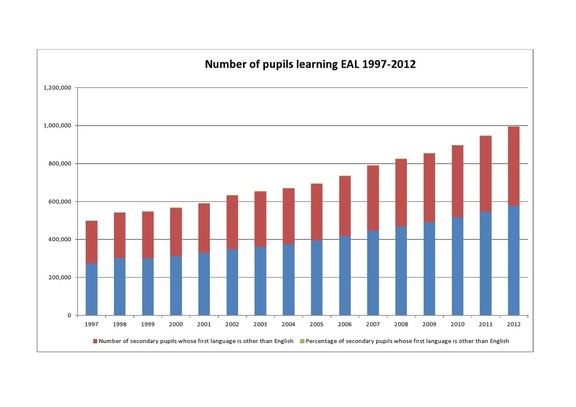

The lack of a languages strategy for schools has been lamented by many and recently with the introduction of the EBacc languages are being given a higher profile and gradually the numbers of pupils studying languages is increasing. Sadly, though much of these positive moves still focus on Modern Foreign Languages and creates a false dichotomy between MFL and so called ‘Community Languages’ many of whom ironically are world languages and have many millions of speakers across the globe! This lack of joined up ‘Languages Strategy’ for education continues presently yet it is a missed opportunity for successive policy makers as it to fail to tap into and embrace the many positive aspects of bilingualism. This month’s British Council Report ‘The Languages for the Future’ report identifies a range of languages [1], including many spoken by migrant communities as being essential to the UK over the next 20 years. These languages were chosen based on economic, geopolitical, cultural and educational factors including the needs of UK businesses, the UK’s overseas trade targets, diplomatic and security priorities, and prevalence on the internet. But, according to an online YouGov poll of more than 4000 UK adults commissioned by the British Council as part of the report, three quarters (75%) are unable to speak any of these languages well enough to hold a conversation. It certainly seems time for policy makers to pay heed to the latest research and consider how it can support the learning of languages amongst its population, including the maintenance of languages already spoken within communities. [1] Spanish, Arabic, French, Mandarin Chinese, German, Portuguese, Italian, Russian, Turkish and Japanese I am currently writing a paper on the present situation with regards to EAL pupils in England, which will cover the following: · Provide an overview of the official approaches to EAL over the past 30 years or so, · Briefly outline associated research into EAL pupil’s both national and international, · The current attainment of EAL pupils in England · Highlight examples of best practice in schools across regions and LA · Stress the urgent need for a more nuanced and focused strategy for pupils for whom English is an additional language at a national level · Outline recommendations The intended purpose of the paper is to encourage reflection, debate and forward strategy at a time when the current education system is undergoing considerable change leading to both potential opportunities and considerable challenges. In such situations there is the strong likelihood that the needs of some groups of pupils are missed especially when the spotlight is shifted to other groups who are deemed more worthy or more in vogue, leading to unnecessary binary approaches to raising attainment. This blog posting summarises some of the key headlines of this paper. The DfE recently released the latest statistics on the number of pupils for whom English is an additional language (EAL). These figures show that there are now over 1 million pupils whose first language is other than English, with the percentages in primary standing at 18.1% compared to 17.5% last year and 13.6% for secondary showing a 0.7% increase on last year. These annual increases show the growing number of EAL pupils in schools in England and are illustrated in the graph below: The trend shows that the numbers of EAL pupils are likely to continue to increase. As a result teaching EAL pupils is now an issue for all schools at a time when many professionals within education report that they do not feel well trained in addressing pupil’s EAL needs (read my earlier blog on EAL and ITE &CPD needs here). The attainment results over the past few years have shown that outcomes for EAL pupils have improved significantly leading to the attainment gaps virtually closing at a national level in terms of the gold standard 5 A*-C including English & Maths grades at GCSE. The graph below shows how the attainment gap at a national level has virtually disappeared over the past five years. These results for the last five years show a vast improvement compared to previously when most EAL pupils were significantly languishing behind their peers. Just a generation ago it was routine for bilingual pupils to be sent to separate language centres to learn English before being admitted to schools. This gradually changed to EAL pupils being sent to language centres within schools and being taught separately until it was felt that they would be able to cope with the mainstream curriculum of their peers. If EAL pupils were extremely lucky then they may have made it directly into the mainstream, escaping the need to receive an alternative curriculum but were often left to sink or swim, without any support or appreciation of their EAL needs. Nowadays these practices would be deemed abhorrent and totally going against well- known research of how bilingual pupils acquire and learn languages. Although these incidents happened approximately 25 – 30 years ago and illustrate the distance that has been travelled so far, they also highlight the journey which still needs to be travelled, until we get to a situation whereby all teachers have the understanding, knowledge and skills to address the needs of EAL pupils within the mainstream context and deliver high quality teaching and learning to enable all EAL pupils attain national expectations. It therefore seems appropriate to briefly take stock of where we are now in relation to meeting the needs of pupils for whom English is an additional language in England and look at the potential of where we should be in the very near future. I have listed a few key headlines below: · At national levels gaps are closing as the graph above shows. These results also mean that some of the powerful negative myths that have perpetuated in relation to bilingual pupils and their attainment are being exploded, resulting in the fact that bilingual pupils can and should achieve academic excellence as a matter of course. · Better outcomes in attainment mean that more EAL pupils have the potential to accrue the benefits of higher education. This should contribute to better opportunities for gainful employment and improved life chances resulting in economic, social and health benefits for many more community members in the future. · Generally most minority ethnic pupils have higher proportions of pupils for whom English is an additional language, with the exception of Black Caribbean pupils. This means that the positive aspects of being bilingual such as those outlined by many academics such as Jim Cummins, Colin Baker, Stephen Krashen, Tove Skutnabb- Kangas and more recently Ellen Bialystok can be used as a lever to support the learning of minority ethnic pupils currently not performing in line with their peers nationally. · Indian and Chinese pupils have been performing much higher than their peers for many years now. Both of these groups have high proportions of bilingual speakers, with over 80% of Indian pupils and 73% of Chinese pupils speaking English as an additional language.[1] More recently the performance of Bangladeshi pupils nationally has also accelerated with impressive performances. Previous reasons cited for Indian and Chinese pupils academic success have been attributed to lower rates of free school meal eligibility in these groups at 12% for Indian pupils and 14% for Chinese pupils. However, the performance Bangladeshi pupils, with one of the highest free school eligibility figures at 52%, add to the growing body of evidence which shows that pupils eligible for free school meals also perform very highly, setting the precedence for others to follow. · There is growing evidence which is exploding many of the myths surrounding EAL pupils. An example of this of is the recent research undertaken by Professor Sandra Mc Nally et al from the London School of Economics, Centre for the Economics of Education. Their research shows that EAL pupils do not negatively impact on standards for non-EAL pupils. For further details read my previous blog here) HOWEVER, despite the seemingly positive picture emerging at a national level, there remain significant CHALLENGES · There are extreme variations in EAL pupil’s attainment by region which the national figures mask. Nationally 58% of EAL pupils in England achieved 5 A*- C in English in Mathematics in 2012. However, EAL pupils in London performed 4.5 percentage points higher at 62.5% compared to those in Yorkshire & Humber who performed nearly 10 percentage points lower at only 48.5%. The graph below shows the regional variations in EAL pupils attainment 5 A*-C in English and Maths in 2012 [1] Figures cited are from ‘Ethnicity and Educational Achievement in Compulsory Schooling’ by Christian Dustmann, Stephen Machin and Uta Schonberg in The Economic Journal 2010. · EAL pupil’s performance within particular LA’s shows further huge variations in attainment with only 32.7% of EAL pupils achieving the gold standard at GCSE in Hereford LA compared to 82.8% of their peers in Kensington and Chelsea or 82% in Sutton. These huge disparities which continue to exist in different LA’s show the necessity to look beyond the national picture. Presently, where you live in England seems to exert a great influence of your educational outcomes which is morally unacceptable. · The success in closing of the gap of EAL pupils nationally can be attributed to a large extent to the higher performance of EAL pupils in London and West Midlands, where there are larger concentrations of EAL pupils, with improvements in London largely due to the success of ‘The London Challenge’. Amongst the various strategies which have been cited in accounting for the success of the London Challenge, the Pan EAL London EAL Strategy is worth highlighting for particular attention. The Pan EAL London Strategy enabled LA’s to receive additional funding to support effective teams to provide support for EAL pupils and to spread this expertise across London. The effectiveness of this work has been highlighted by M Hutchings and A Mansaray in ‘A review of the impact of the London Challenge (2003-8) and the City Challenge (2008-11)’ submitted as evidence to Ofsted’s ‘Access and Achievement’ Review a few months ago. · There are further variations in EAL pupil’s performance when looking at other characteristics such as ethnicity, socio-economic background and gender. Socio-economic gaps are more pronounced for White British groups compared to most ethnic minority groups. For some minority ethnic groups this is because non – free school meal pupils are less likely to come from families with higher socio-economic and professional backgrounds so the differences are less marked. Since national data is not available by ethnicity and EAL, ethnicity data can provide a useful indicator of performance, bearing in mind the intersections of ethnicity and EAL. The differences in performance by FSM eligibility and ethnicity are shown in the graph below: · Bangladeshi pupil’s performance nationally is skewed by the fact that over half of all Bangladeshi pupils live in London, with about a third located in Tower Hamlets alone. Tower Hamlets is one of the success stories and had an impressive 67.8 % of EAL pupils attain 5 A*- C including English and Mathematics in 2012 which is nearly 10 % above the national average. · There are considerable differences in attainment when looking at key stages with outcomes much lower for all minority ethnic and EAL pupils at the start of schooling and even at the end of primary for most groups compared to secondary where most of the gains for EAL pupils are made. This is well documented by researchers.[1] This means the potential outcomes of EAL pupils could be accelerated further if the progress seen in secondary, particularly at KS 4 was replicated in primary. · Gender differences also impact across various regions with EAL girls generally performing much higher than both non-EAL and EAL boys with the exception of the Yorkshire & Humber region where EAL girls performed marginally better than EAL boys but lower than non – EAL girls and boys. The graph below shows how EAL and Gender characteristics lead to extremely differential outcomes across regions with EAL boys in the South West performing the lowest in 2012 leading to a gap of 16.9% compared to their peers in London. [1] ‘The Dynamics of School Attainment of England’s Ethnic Minorities’by Deborah Wilson, Simon Burgess and Adam Briggs CASE paper 2006, ‘A Comparative Analysis of Bangladeshi and Pakistani Educational Attainment in London Secondary Schools’ by Sunder Divya and Layli Uddin 2007, Drivers and Challenges in Raising the Achievement of Pupils from Bangladeshi, Somali and Turkish Backgrounds by Steve Strand et al 2010 and Figures cited are from ‘Ethnicity and Educational Achievement in Compulsory Schooling’ by Christian Dustmann, Stephen Machin and Uta Schonberg in The Economic Journal 2010. · The regional differences are further compounded when looking at the performance in LA’s e.g. only 30 % of EAL boys and 39.3 % of EAL girls in Blackpool LA achieved the gold standard at GCSE last year. This is a stark contrast to the 81.7 % of EAL boys and 84.3 % of EAL girls in Kensington & Chelsea who achieved this benchmark.

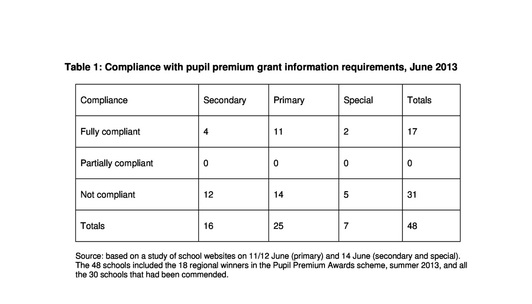

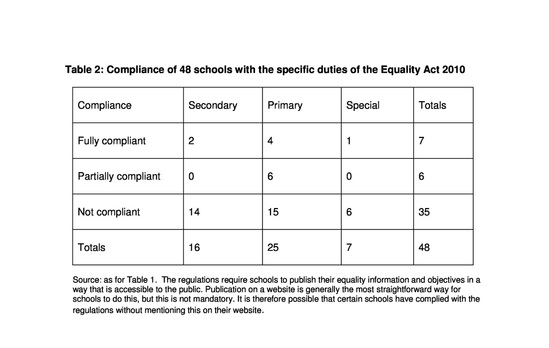

· Another consideration is in relation to the performance of EAL pupils in mainly white LA’s. The issues are complex and may be down to the arrival of newer communities or lack of strategy and expertise in supporting EAL pupils particularly when EAL pupils are dispersed across an LA and are considered to be relatively small. It seems that we in England are at the cusp of making sustained changes in ensuring better educational outcomes for our EAL pupils, many of whom until recently have been languishing behind their peers. Taking a long view there is much to be celebrated and built upon. However, considering the fact that it has taken us over 30 years to get to this stage, with the gains by no means sustained nationally for all key stages and certainly not across regions and LA’s it is imperative that the best practice that is evident is disseminated as a matter of urgency to so that the momentum continues to be built upon. Sadly, although the national results for EAL pupils are applauded there is little if any emphasis on meeting the needs of EAL pupils in other areas or indeed in using flagship policies such as the Pupil Premium to stress the interlinked relationships that exist for EAL pupils and other characteristics such as free school meal eligibility. A more focused and nuanced policy at a national level is required to ensure that the potential of all EAL pupils, irrespective of ethnicity, socio-economic backgrounds and gender is realised and the impact of where you live or which you school you go to does not result in a lottery in achieving better educational outcomes. The headlines are based on a detailed paper which is currently being written by Sameena Choudry on EAL pupils in England and the need for a nuanced strategy to close the gaps. Bill Bolloten, Sameena Choudry and Robin Richardson This article has been republished from LeftCentral. It is also available to read on IPP The pupil premium grant (PPG) is a flagship government scheme for schools. Next week it will be praised and celebrated at the 2013 pupil premium awards ceremony organised in partnership with the Department for Education (DfE). An independent panel of experts has judged which schools have best used the PPG to make a real difference to the attainment of disadvantaged pupils. However, almost two-thirds of the 48 schools that have been named as regional winners or commended for the awards ceremony have so far failed to comply fully with regulations relating to accountability. Also, about four-fifths of them appear to have ignored or misunderstood the regulations concerning accountability in the Equality Act 2010. ‘Take it and use it as you think fit. But …’ ‘Take it, said Nick Clegg in 2011 when introducing the new grant to headteachers, ‘and use it as you see fit.’ He added a stern warning: ‘But know that you will be held accountable for what you achieve.’ The basic principle he was expressing – local freedom combined with public accountability – is central in the coalition government’s public discourse across a wide range of public policy. In the case of the PPG, there are three main ways in which school leaders are held accountable for the decisions they make: a) through the performance tables which show the performance of disadvantaged pupils compared with their peers; b) through the Ofsted inspection framework, under which inspectors focus on the attainment of various pupil groups, including in particular those which attract the pupil premium; and c) the requirement to publish online information about the pupil premium for parents and others. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has noted with approval that the UK government requires schools to report to parents on how they have used additional money to close gaps in attainment connected with poverty and economic disadvantage. How schools present the information in their online statement for parents is a matter for each school to decide for itself. There is certain minimum key information, however, which must by law be included on a school’s website. The amended school information regulations relating to this came into force in September 2012. Yet, as of June 2013, it appears that only a third of schools in receipt of the grant are fully complying with it. Background Monies previously allocated to other priorities have been redirected since 2010 towards children from low-income households, defined for the purposes of allocating the grant as those who are eligible for free school meals, or who have been eligible at any time in the last six years, and whose parents or carers have registered for free meals (though they may not have actually claimed them). Schools also receive funding for children who have been looked after continuously for more than six months, and for children of service personnel. In the last financial year the grant was £623 per pupil. Since April 2013 it has been £900 per pupil. For children of service personnel it is £300. The grant does not have to be spent only on pupils who are eligible for free school meals. Its use must, however, be directed towards reducing or closing gaps in attainment connected with poverty and economic disadvantage. The total annual funding will be £2.5 billion by 2015. In his spending review announcement on 26 June 2013 Chancellor George Osborne pledged that the grant will continue in real terms – ‘so every poor child will have more cash spent on their future than ever before’. In order that schools can be accountable to parents and others, they are required to publish on their website 1) their PPG allocation in respect of the current academic year, 2) details of how it is intended the allocation will be spent, 3) details of how the previous academic year’s allocation was spent, and 4) the impact of this expenditure on the educational attainment of pupils at the school in respect of whom the grant funding was allocated. Study of 48 shortlisted schools In June 2013 a study was made of the websites of the 48 schools –16 secondary, 25 primary, 7 special – that are regional winners or commended in the pupil premium awards scheme. Schools were judged in this study to be fully compliant with the statutory school information regulations if they had published all four of the required pieces of information; partially compliant if they had published at least three; and non-compliant of they had published no more than two, or had published nothing at all. Schools applied for the award on the basis of criteria that did not mention the requirement to publish information for parents. The picture relating to the 48 schools shortlisted in the PPG awards is shown in Table 1 below. The Equality Act 2010 Principles of transparency and accountability determine not only how the pupil premium grant operates but also how public bodies are required to show due regard for the aims of the Equality Act. Under the Act’s specific duties, schools must a) publish information that demonstrates adequately an awareness of the diversity of the school population and how have had due regard for the aims of the Act, and b) prepare and publish at least one specific and measurable equality objective. To count as specific, an objective should state the outcome that the school aims to achieve. To count as measurable, the desired outcome must be quantifiable so that parents and the community can assess whether the school has been successful. In order to determine their compliance with the accountability rules in the Equality Act, a study was made in June 2013 of the websites of the 48 schools featured in the pupil premium awards scheme. A school was judged to be fully compliant if it had published relevant information and at least one specific and measurable equality objective. It was judged to be partially compliant if it had published either equality information or measurable equality objectives, but not both, or if it was clearly aware of the duties even if it did not appear to have understood them. It was found that almost three-quarters of the schools shortlisted for the pupil premium awards (35 out of 48) failed to comply at all with the requirement to publish equality information and objectives. Less than one in six of them complied fully. The overall picture is shown in Table 2. Concluding notes

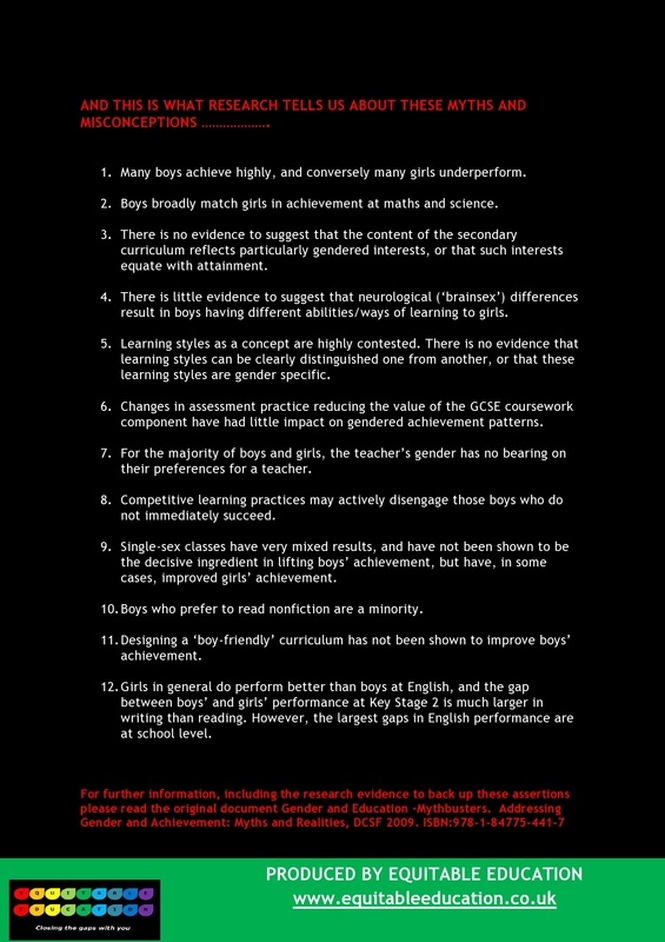

The 48 schools whose websites were studied for this article are probably all making good use of the pupil premium grant, and the judges who selected them for special praise have made good decisions. It is surely surprising, however, that so many have not complied with regulations relating to accountability. The principal reasons for non-compliance appear to lie in the failure of the government to provide adequate advice, guidance, challenge and support. Most of the schools which are non-compliant are probably unaware of the regulations and requirements, for the government has been generally light-touch in its publicity about them. Prior to 2010 schools would have received advice and support in relation to a project such as the pupil premium grant from their local authority. There would have been training and professional development opportunities, exchange of information about relevant research findings, and – crucially – much collaboration and joint reflection within local clusters and families of schools. Local networking along such lines is now much more problematic. It continues, however, to be an urgent necessity, and is a matter which requires the government’s attention. Guidance, research and commentaries on the pupil premium grant have recently been published by, amongst others, the Sutton Trust, the Institute for Public Policy Research, the Department for Education and the Young Foundation. These reviews are much more substantial than the small-scale survey reported in this article. Their recurring conclusion, however, is that schools need more advice, training and challenge than they have so far received. Understandably and rightly the government does not wish to micro-manage what happens in schools. It nevertheless has a responsibility to ensure that good practice is widely shared. With the declining capacity and influence of local authorities, this responsibility is of urgent importance. At the same time, the government needs to lead consideration of the links, connections and similarities between economic inequality and other forms of inequality, particularly those which are highlighted in the Equality Act. Each pupil stands at the intersection of several different strands of equality and inequality. For example, every child from a low-income household not only has a socio-economic location affected by poverty but also is a boy or a girl and has an identity in terms of ethnicity; many have special educational needs amounting to a disability; many have a religious identity which is important to them; all have a sexual identity. Some of a child’s educational needs cannot be appropriately met without reference to distinctive aspects of their experience, identity and reality – they are not ‘all the same’. One universal size does not fit them all. Schools should therefore be encouraged both to explore intersectionality in their use of the premium grant and to pay due regard to economic disadvantage in their responses to the Equality Act. This is especially crucial in view of the fact that low income frequently intersects with the issues named in the Equality Act, particularly in relation to ethnicity, religion and disability. Overall, about 18 per cent of all young people are eligible for free school meals and therefore for the pupil premium grant. But for white pupils the proportion is slightly smaller, 16 per cent, whilst for certain others it is considerably higher. For children with special educational needs it is twice as high as for other children. ‘It is unacceptable,’ said the coalition government when it came to power in 2010, ‘for educational attainment to be affected by gender, disability, race, social class, sexual orientation or any other factor unrelated to ability. Every child deserves a good education and every child should achieve high standards. It is a unique sadness of our times that we have one of the most stratified and segregated school systems in the world …’ Such ideals and concerns sound like empty rhetoric if schools do not comply with rules of accountability. Bill Bolloten tweets at @SchoolEquality and Robin Richardson at @Instedconsult. There is further information at www.insted.co.uk (Robin Richardson). The ‘gender effect’ is a matter of concern not only for England but many countries around the world. As a result, gender and educational attainment continues to be the focus of research. Initially the focus was on ‘girls’ underachievement’ in the 1970’s but since the 1990’s, however, the discourse has shifted significantly to focus on ‘boys’ underachievement.’ This issue regularly preoccupies the minds of many politicians and parts of the media, and from time to time it gives way to a moral panic. However, in terms of inequalities in education it is worth remembering that class has over five times the effect and ethnicity has twice the effect compared to gender. [i] That is not to say that that the effect of gender is not still significant but it should be considered within this context. The actual issues affecting inequalities in education can be quite complex and to gain a better understanding of these issues it is important to look at how class, ethnicity and gender come together to interplay on educational outcomes. It is recommended that senior leadership teams and staff in school look holistically at the needs of their particular pupils and groups of pupils who are currently underachieving before developing strategies to address these needs. It is also worth remembering that there are more variations within the overaching groups of ethnic minority and pupils eligible for free school meals, as there are between them too, largely because groups are not homogeneous and have a wide variety of needs. This fascination with the ‘gender effect’ has resulted in many myths and misconceptions being perpetuated. For colleagues interested in addressing gender inequalities Equitable Education has produced the following Infographic exploding 12 myths and misconceptions commonly associated with gender. The Infographic has been based on the publication called ‘Education and Gender – Mythbusters. Addressing Gender and Achievement: Myths and Realities’ produced by the DCSF in 2009 and written by Gemma Moss, Becky Francis and Christine Skelton. [i] Gillborn D & Mirza H (2000), ‘Educational Inequality: Mapping Race, Gender and Class. A Synthesis of Research’. Ofsted London The realities to these myths are outlined below: The original publication ‘Education and Gender – Mythbusters. Addressing Gender and Achievement: Myths and Realities’ produced by the DCSF in 2009 and written by Gemma Moss, Becky Francis and Christine Skelton it is available here in PDF format for you to download. It includes further information, along with research evidence to back up these assertions.

We shall be coming back to this topic in future postings, so do visit our blog regularly to keep updated. In the meantime, should you require specialist advice and support in addressing educational inequalities in.your school, please do contact us at Equitable Education by e-mailing us on [email protected]k If you would like a PDF version of our Infographic to use in your school, please get in touch with us by using the e-mail above. We look forward to hearing from you. Equitable Education has produced a Model Pupil Premium Policy Template and accompanying guidance for schools to use. Both are available free for schools to download from the Guardian Teacher Network. Click here for the Model Policy Template and here for the accompanying guidance.

The Pupil Premium Policy and guidance have been written to support schools to produce a policy of their own. The policy enables all colleagues in a school community to be clear as to how this additional funding is to be used to reduce inequalities, what their role is in narrowing the gaps for disadvantaged pupils and how the school will demonstrate impact. The supporting guidance assists schools in tailoring the policy to meet the needs of their particular pupils. It also pulls all the latest research and tools they can use together in one place for ease of use saving time and effort. The Pupil Premium Policy Template on the Guardian Teacher Network is a PDF. Should schools require a Word version to make it easier for them to produce their own, this is available on request from Equitable Education on [email protected] for a copy. Equitable Education provides workshops for schools and their governing bodies to facilitate the production of their own Pupil Premium Policy, using all the latest evidence based research of ‘what works’ and evaluation tools that are available to use. We can support you in personalising the workshop, so that it is tailor made to meet the particular needs of your pupils eligible for free schools meals. Please get in contact with Sameena Choudry on [email protected] to discuss the needs of your school and how we can support you in ensuring maximum impact in using your Pupil Premium effectively in narrowing the gaps for your disadvantaged pupils. For further information on the Pupil Premium and what you as a school needs to meet the Ofsted and Pupil Premium Grant requirements, please read the blog posting below. Many schools are receiving additional funding for their pupils who are eligible for free schools meals through the Pupil Premium Grant. This is also given for children who have been looked after for more than six months and children of service personnel. The purpose of the Pupil Premium is to reduce the inequalities in educational attainment that currently exist between disadvantaged pupils and their more affluent peers.

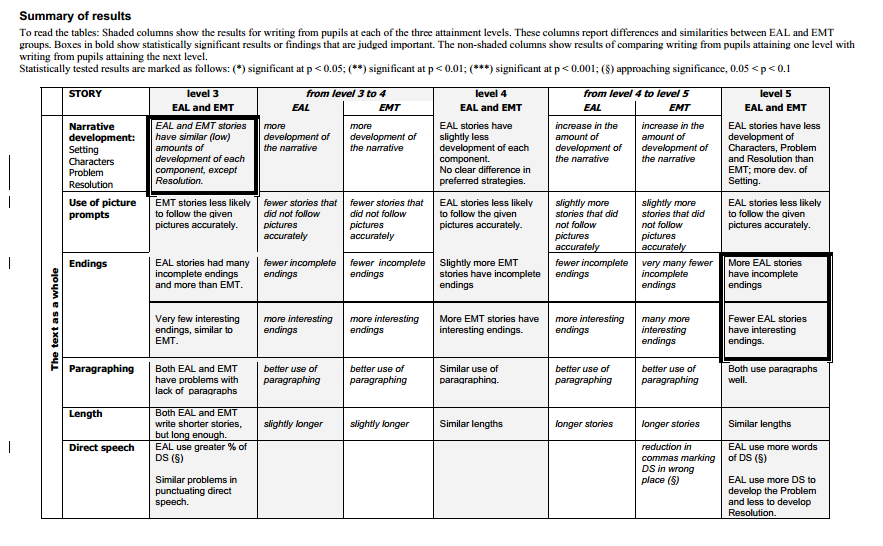

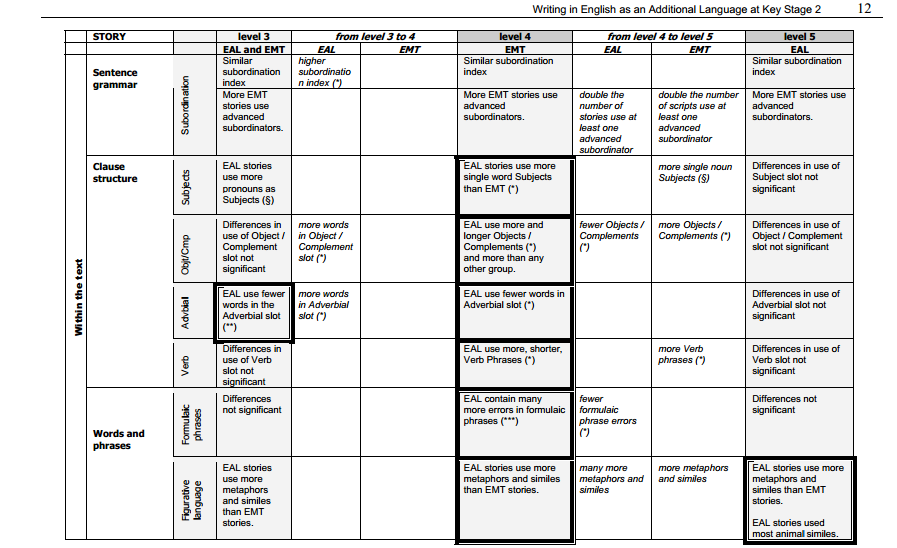

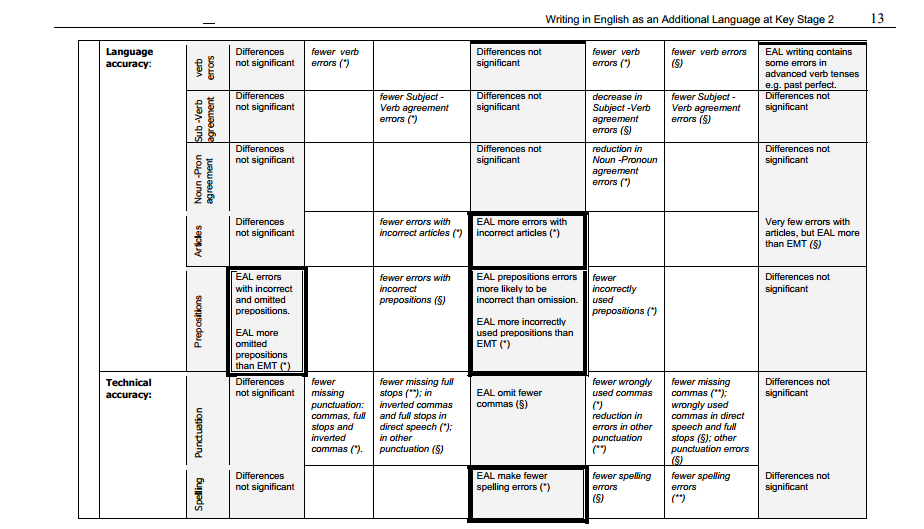

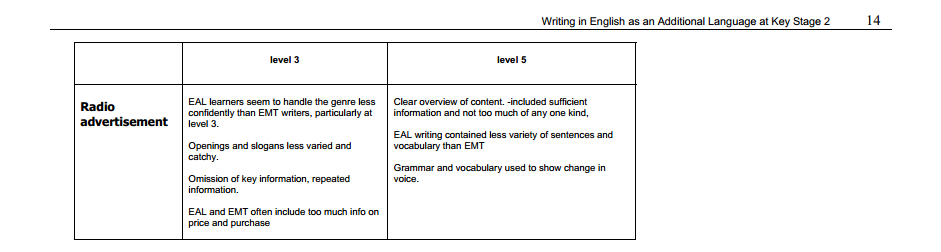

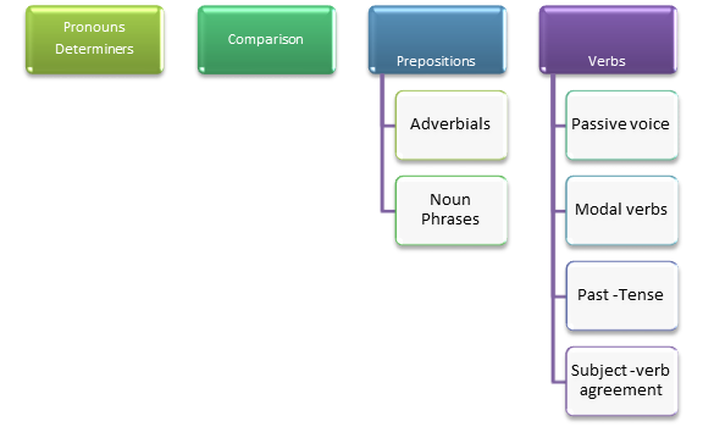

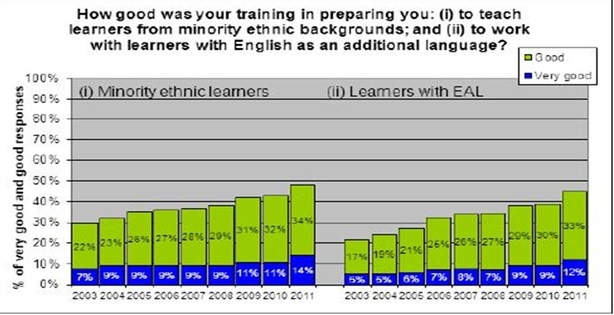

The Pupil Premium Grant is not ring-fenced by the DfE and schools have freedom to use the Pupil Premium as they see fit, based upon their knowledge of their pupil needs. ‘It is for schools to decide how the Pupil Premium, allocated to schools per FSM pupil, is spent, since they are best placed to assess what additional provision should be made for the individual pupils within their responsibility.’ DfE As a school in receipt of Pupil Premium funding, you are accountable to your parents and school community for how you are using this additional resource to narrow the achievement gaps of your pupils. New measures have been included in the performance tables published annually on a national level. They capture the achievement of disadvantaged pupils covered by the Pupil Premium. Under The School Information (England) (Amendment) Regulations 2012, Schedule 4 there is specified information which has to be to be published on a school’s website. Section 9 of this regulation requires schools to publish: ‘The amount of the school’s allocation from the Pupil Premium grant in respect of the current academic year; details of how it is intended that the allocation will be spent; details of how the previous academic year’s allocation was spent, and the effect of this expenditure on the educational attainment of those pupils at the school in respect of whom grant funding was allocated’. In addition, under the Ofsted Inspection Framework 2012, there is a stronger focus on improving the learning and progress of different groups and on narrowing gaps in standards. As a result, Ofsted carefully scrutinises the use of the Pupil Premium and the impact this is having on narrowing the gaps. Please note that this permeates across all four areas of the new Ofsted framework and your governing body has an important role in monitoring the use of the Pupil Premium and accounting for its effectiveness. Equitable Education has produced a free Model Pupil Premium Policy Template for schools to use, with accompanying guidance. Both documents are available from the Guardian Teacher Network and can be downloaded here. Equitable Education can provide workshops for your school and your governing body on the Pupil Premium. this which will be tailor made to meet the specific needs of your pupils eligible for free school meals. These workshops will also take you through the latest evidence based research of ‘what works’ and evaluation tools to ensure that members of your school community know how to narrow the gaps and can demonstrate impact. Please feel free to get in touch with Sameena Choudry on [email protected] to discuss your school needs. We can also provide you with a Word version of the two documents produced by Equitable Education. These are available by e-mail from [email protected] We look forward to hearing from you. Over the last few years there has been either a significant reduction, or in some cases a cut in Local Authority services providing specialist consultancy support for teachers to address the needs of pupil’s for whom English as an additional language (EAL), even though many EAL pupils at Key Stage 2 continue to underperform, especially in regions outside of London. Some schools may have specialist EAL teachers employed who have the expertise to support teachers to raise the attainment of these pupils but more often than not it is often left to class teachers, who may or may not have relevant training and specialist skills to address the needs of advanced EAL learners. Many teachers may not be aware of the research and resources that can support teachers in improving the writing skills of advanced EAL learners. The research on ‘Writing in English as an additional language at KS 2’, undertaken by Professor Cameron and Dr Besser at the University of Leeds on behalf of the DCSF is very useful. This was shortly followed by Ofsted’s ‘Could they do even better’ which identified the need for teachers to be aware of the specific linguistic needs of advanced bilingual learners, along with detailed case studies to illustrate the difference that effective intervention, addressing specific linguistic features, can make to the development of the writing skills of advanced bilingual learners. A few years later PNS developed materials entitled ‘Teaching units to support guided writing in English as an additional language’, for teachers and teaching assistants to support the development of writing of advanced EAL learners. Although these publications may now seem dated, they are in fact still very relevant and pertinent. They are recommended for use by teachers who wish to find out more about the specific issues their advanced EAL learners face in writing in KS2, and how they can support their pupils to do better in their KS 2 writing SATS papers. Professor Lynne Cameron and Dr Sharon Besser analysed Key Stage 2 SATS writing papers in 2003 to see if there were any significant differences in the writing of Year 6 pupils for whom English was an additional language (EAL), with a specific focus on advanced learners and those for whom it was their mother tongue (EMT). They compared 264 scripts by focusing on text, sentence and word level. The 2003 scripts had two tasks - one story and a radio advertisement. The story writing task consisted of a set of pictures leading to a problem for the main characters, which pupils had to resolve and conclude. The shorter task was to write an advertisement for local radio to persuade listeners to buy a new toy. Their analysis of the scripts are summarised below in tables from their publication (pages 11-14), with significant differences highlighted by the dark boxes. Based on the above findings they highlighted that the following grammatical features may present particular challenges for EAL learners: Teachers preparing their advanced EAL learners for KS 2 writing tests may wish to use the blank proformas included on pages 90-93 of their publication for analysing the writing produced by their own pupil’s. The publication also provides detailed annotated examples of the completed profromas, which the researchers themselves produced when analysing the scripts themselves.

The teaching units can be used by trained adults working with small groups of children in Years 2-6 or as part of quality first teaching in lessons. Equitable Education is able to provide specialist advice and training to support all staff working with advanced EAL learners. For further information, please contact Equitable Education on [email protected] During the course of over 25 years in education, I have been privileged to have had the opportunity to work alongside hundreds of primary and secondary schools leaders in Yorkshire. The vast majority of schools I have spent most of my career in are those which would be deemed to be in “challenging circumstances”[i]. These schools are the ones I proactively chose to focus my own teaching career in because of the potential to make a greater difference. Recently, I have been reflecting on the specific characteristics of successful leaders of challenging schools who I have seen successfully close the gaps in attainment. What is it that they do on a regular and sustained basis for their pupils and communities, which makes the difference between success and failure of a school and its community ?

There is much research on what constitutes successful school leadership.[ii] However, there has been much less research on the nature of successful leadership of schools facing challenging circumstances[iii] with attention being drawn to this subject only a decade ago. In 2009, Ofsted published two key reports[iv] outlining characteristics of schools which were outstanding and excelled against the odds, in terms of their intake of pupils and location. The same year the then DCSF also published two phase reports[v] with a main focus on white pupils eligible for free school meals. There seems however, even much less written about leadership of multi-ethnic schools. Following Gillborn and Gipps’[vi] seminal research in 1996, which highlighted the under-performance of some minority ethnic pupils, Blair and Bourne’s research[vii] in 1998 highlighted the characteristics of outstanding multi-ethnic schools. Subsequent to this, the only other main research which focuses on successful multi-ethnic leadership was undertaken by Dimmock et al[viii] in 2004, followed by Walker et al,[ix] which used a case study approach of ‘good leaders’ of multi-ethnic schools, setting the challenges they face within an international context. Currently, with the focus on closing the gap and raising attainment in schools near or below floor targets, many of whom are schools facing challenging circumstances, HMCI Wilshaw has ordered a review of “Access & Achievement”[x]. The purpose of this review is to focus on the issues facing urban leadership. He has also engaged an expert panel to come up with new and radical solutions to address the issues facing deprived communities. After a year of deliberations, the expert panel is due to report back in May this year. Based on this research and my own observations of working closely with these leaders who had a proven track record in closing the gaps, I decided to reflect on what I thought were the most compelling specific characteristics they shared and came up with this list, much of which resonates with the research outlined above. 1. Overarching commitment to fairness, equality and social justice. This commitment drives the schools mission, values and practice in schools and is their ‘raison d’etre’ for leading schools in challenging circumstances. I have observed that that these leaders are confident and command respect from their school community, but at the same time have a sense of humility and modesty, with an eagerness of wanting to learn more about their often changing communities. They have high expectations of their staff, pupils and their communities and ensure that this is permeates across everything the school does. 2. Distributed leadership at all levels The demands of working in a school facing challenging circumstances is immense and one of the key ingredients is making sure that all leaders in the school passionately share in the Head’s vision and commitment to fairness, equality and social justice. This team of leaders play a pivotal role in ensuring that the many difficult issues they come across on a daily basis are dealt with promptly and effectively, without distracting them from the smooth and efficient running of the school and their core focus of delivering high quality teaching and learning opportunities for their pupils. 3. Delivery of Quality First Teaching, with a high emphasis on literacy skills and the use of swift and effective interventions for those at risk of falling behind. The leaders I am referring to relentlessly focus on the delivery of high quality first teaching by all their staff, from teachers to support staff, each with a key role to play in accelerating pupil’s progress and learning. They ensure that all staff are experts in teaching literacy, which is taught explicitly and consistently across the curriculum, with interventions carefully monitored for progress and impact. They create opportunities for their pupils and parents to engage in fun literacy activities, even when parents may be less confident in their own literacy skills or do not have the literacy skills in English. They are solution focused by using innovative strategies such as use of technology in the form of “Talking books” or using bilingual reading resources to overcome barriers. Another key feature of these leaders is that they ensure that the curriculum offered to their pupil’s is reflective of their backgrounds and interests, including positive portrayals of diversity. This demonstrates to pupils and their parents that they are respected and their heritage is valued. A rich variety of enrichment activities are used as a way of enhancing the learning experiences of pupils and are carefully planned at key points in the delivery of the curriculum to actively support learning in a practical, fun and meaningful way. Often when affordability is an issue they use school funds to either subsidise or fully pay for the costs. 4. Use effective and regular tracking systems which are not only disaggregated by different groups (i.e. gender, socio-economic status, ethnicity, language background and special educational needs) but also look at how structural inequalities can come together and impact on pupil outcomes. They use their tracking data at regular intervals to monitor pupil progress and ensure that both quality first teaching and interventions are delivering faster than average rates of progress, which they know is essential for their pupil’s to get to age related expectations, as many of their pupil’s start at lower levels of attainment on entry. They use this tracking information to deliver bespoke and personalised learning suitable for meeting the needs of either groups of pupils or individual pupils. They expect their pupils to reach at least age related national expectations, irrespective of their starting points and although they are aware of both LA and national performance of particular groups of pupils, they continue to set expectations for them to reach the national benchmark rather than that of their peers, as they know this will perpetuate lower standards. 5. They know each and every child, their background and circumstances. They use this knowledge to ensure that the holistic needs of the child are met but without compromising on the high expectations they have of them. They show “tough kindness with empathy” rather than expecting less of them because of their particular circumstances. On many an occasion, whilst on a learning walks, with these outstanding leaders they are vigilant and aware of their pupils’ needs and interactions. They also make it their business to know more about the personal circumstances of their pupils as do all Headteachers. However, in addition they make it their business to be knowledgeable of the extra learning their pupil's undertake at weekends and after school, including competency in other languages the pupil's may be learning or speak within the community and at home, as they can see the benefits of bilingualism as a tool for learning. 6. Proactive engagement with the community They recognise the important role that parents and carers play in the lives of their children, especially since they know that schools only have pupils for 15% of the time. They, therefore proactively look at ways in which the remaining 85% of the time their pupils are with their parents can be maximised. They do this enabling their school to become a hub of the community, providing extended services in partnership with other key services so that wrap around care is available when needed. They also enable successful partnerships to be forged between their school and local complementary schools, who provide additional study support in language, religious or academic study. They work in synergy to meet the holistic needs of the same groups of children, with a collective emphasis on high attainment. 7. They nurture and develop their own staff and governors and try to ensure that they are representative of the community their school serves. These leaders understand that the school is at the heart of their local community and that pupils need to see positive role models from the community in its staff and governing body. They therefore, nurture and develop staff and governors by providing high quality professional development opportunities and coaching. This also assists in alleviating some of the difficulties they can face in recruiting and retaining staff and governors. In many cases, I have seen these schools develop strong partnerships with local universities and colleges who place trainee teachers in their schools. The advantages are that the school is able to train these teachers in both the generic and specific skills and competencies needed for teaching in urban schools, thereby having a ready pool of potential teachers to recruit from. They also benefit from having highly qualified additional staff in their school which means they can provide more focused quality teaching to their pupils, at minimal cost. These observations based on my own working closely with these leaders are closely borne out by the research. However, the key issues is not the identification of these key characteristics but the translation of these into practice. We now have, more than ever before much evidence based research to guide us in what works the best. Take for example the latest Education Endowment Foundation, Teaching and Learning Toolkit Research which has shown that providing effective feedback is the single most powerful way of improving attainment. However, less than 3% of teachers in surveyed identified this as a top spending priority for the Pupil Premium. This example illustrates the problem. Therefore, the issue is even though we know the effective characteristics of outstanding leaders who close the gaps in their schools, how do we ensure more schools in similar circumstances have leaders with these specific outstanding characteristics? Bearing in mind the growing emphasis on school to support and system leadership to drive up standards across localities, it is difficult not to share some of the concerns highlighted by HMCI Wilshaw when giving evidence to a cross –party commons committee earlier this week. He stated “The great challenge for the future is to identify system-wide leaders for our poorest areas because at the moment we have got more good head teachers serving quite affluent communities who are national leaders of education who are asked to go into disadvantages communities to support them. I am not sure they have the necessary skills to do that. Some will, some won’t.” I believe that the many of the leaders I have identified above, lead ‘outstanding’ schools according to Ofsted criteria. However, I have also come across many exceptional leaders, who will find it difficult to get this grading for their school in the current framework, even though the progress the pupils make is higher than the national average. Together, these leaders hold the key to raising standards in similar schools, where many of the systemic problems lie. Recognising the specialist and distinct competencies and expertise they have should form the cornerstone of any strategy in driving forward standards for closing the gaps and raising standards for all. [i] i.e. those schools which face multiple challenges in terms of their location (inner city and/or in areas of high social deprivation); student mix (higher percentages of pupils eligible for free school meals, mobility, minority ethnic pupils, new arrivals with English as an additional language needs); facing staffing difficulties in terms of recruitment and retention of key staff; parental attitudes and sometimes histories of the schools themselves with low records of attainment and achievement and therefore under pressure from either being in an Ofsted categories or likelihood of falling into one as a result of being below or near the floor targets. [ii] Alma Harris’s et al’s “10 strong claims about successful leadership”, which built on their earlier work “7 Strong claims about successful school leadership (2006). [iii] Alma Harris & Chris Chapman “ Leading for improvement in challenging circumstances”, 2003. [iv] Ofsted “12 outstanding schools: excelling against the odds” published in 2009, with one for primary and the other for secondary, highlighted the characteristics of schools and leaders that may a significant difference. [v] “Extra Mile: Achieving Success with pupils from deprived communities”. [vi] “ Recent research into the achievements of ethnic minority pupils”. [vii] “Making a difference: teaching and learning in successful multi-ethnic schools”. [viii] “The leadership of multi-ethnic schools: What we know and don’t know about values driven leadership”. [ix] “Priorities, strategies and challenges: Proactive leadership in multi-ethnic schools”, NCSL. [x] This new report follows on from two earlier ones, with the same name undertaken by Ofsted, first in 1993 and then a decade later in 2003. There are two accepted truisms which drive educational standards across the world. The first is 'the quality of an education system cannot exceed the quality of its teachers[1] and the second is that the quality of leadership is the most important determinant of pupil’s success.[2] It is, therefore essential that we have the highest quality of teachers and leaders if we are to continue to raise standards and close the gaps in attainment for different groups of pupils in England. The announcement made by the DfE last week that the Teaching Agency and The National College are to merge under the leadership of Charlie Taylor, will mean that for the first time there will be one executive agency responsible for the recruitment, supply and development of both teachers and leaders for schools in England. The new agency (with a name to be determined) will therefore play an important role in ensuring the highest quality of teachers and leaders for our schools. The purpose of the new agency which will be operational from the end of March this year, is to enable the best leaders and best teachers to work together to develop a self-improving school system and be responsible for the recruitment, supply, initial training and development of teachers. The new agency, will also oversee the development of a cadre of system leaders such as National Leaders of Education (NLE’s), Local Leaders of Education (LLE’s), Specialist Leaders of Education (SLE’s) and Teaching Schools whose remit is to focus on leadership development, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) and school improvement to address under performance across the education system. This merger provides a golden opportunity to refocus energy on the current gaps in attainment in England by enabling system leaders and teachers to develop the requisite skills, knowledge and understanding to address this key challenge, which permeates within and across schools, thereby contributing to the long tail of underachievement. Closing the gaps for different groups of pupils is high on both the DfE and Ofsted’s agenda, with schools being given considerable amounts of additional funding to address the gaps in attainment that exist for pupils who are eligible for free school meals (FSM) through the Pupil Premium[3]. However, although no one disputes the impact that poverty has on attainment which remains a major factor in preventing pupils getting to age related national expectations, there are many other factors such as a pupil’s gender, ethnicity, special educational needs, disability and language background which can and do impact on attainment. Indeed, for many pupils it is not just poverty alone, as many of these groups tend to have rates of FSM than average, but an amalgamation of these factors or “intersectionality” which impacts on outcomes. The new agency will be responsible for recruiting and providing a ready supply of high quality teachers and leaders, with Teaching School Alliances taking on the role of providing high quality professional development. In order to maximise the potential of the teaching workforce it is essential to not only ensure that staff have high levels of knowledge and understanding of the subjects they teach and are able to deliver high quality teaching which impacts on learning and pupil progress, but also it is equally important that they are able to meet the specialist needs of the range of pupils for whom closing the gap remains an issue too. The acquisition of these specialist teaching skills and in – depth understanding and knowledge of individual needs of a range of pupils should be developed alongside teacher’s subject teaching skills from the outset of their career. Presently, there are many teachers who are able to personalise their teaching so that it impacts on all learners in their class and their teaching is classified as “outstanding”, using Ofsted terminology. Others however can find this a challenge and feel less confident in meeting the needs of the wide range of pupils who are currently not performing in line with national expectations. Despite this, they are expected to deliver high quality teaching which impacts on pupil’s learning so that they make faster than average rates of progress in an academic year. In order for them to deliver high quality teaching, specialist demands are made of the teacher for which they may not have received the necessary training, support or professional development opportunities at key points of their teaching career. Using the example of pupils for whom English is an additional language (EAL). This group has been chosen to illustrate the issue facing some teachers, although this would be equally applicable for other closing the gap pupils such as those with special educational needs, disabilities, the more able, certain minority ethnic pupils, and cutting across gender and socio-economic status too. The annual census taken in January 2012 by the DfE showed that there are approximately 1 million pupils whose first language is other than English. The numbers of EAL pupils have more than doubled since 1997 when the first census was taken. The graph below illustrates the increasing number of EAL pupils in primary and secondary schools in England from 1997-2012. [1] “How the world’s best performing school systems keep coming out top”, Morshed M and Barber M, McKinsey and Co. 2007 [2] Seven Strong Claims About Successful School Leadership, Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A. and Hopkins, D, NCSL, 2006. [3] When the Pupil premium was introduced in April 2011, schools received an additional £488 for each of its pupils eligible for free school meals. In April 2012 this was increased to £600 with further increases announced for this year taking it to £900, amounting to £1.65 billion in the financial year 2013-2014. By 2012 the Pupil premium will be worth £2.5 billion of additional money coming into schools. Source DfE Census 2012 and NALDIC. The graph shows that in 1997, the percentage of pupils learning EAL in the primary school population was 7.8%. Over 15 years this percentage had more than doubled to 17.5% by 2012. In secondary the figures were 7.3 % in 1997 compared to 12.9% in 2012. The census also showed a rich tapestry of languages being spoken by EAL pupils in English schools with over 360 different languages being recorded. The percentages of pupils classifying themselves as EAL of course varies considerably from school to school and LA to LA, with Tower Hamlets and Newham LA’s having the largest recorded at 74% and 71% respectively and other large LA’s such as Birmingham with 40 %. In contrast LA’s such as Halton and Redcar& Cleveland only have 0.8% of EAL pupils. Projected demographics show that the number of EAL pupils in schools will continue to grow at comparable rates over the next decade and beyond. However, despite the growing number of EAL learners in school there appears to be no clear nor focused strategy at a national level to address EAL learner’s needs at a time when there can be significant attainment differences between pupils for whom English is an additional language and for those who speak English as their first language. The largest differences between the two are more pronounced at the Early Years Foundation Stage with gaps narrowing to some extent by KS4 as EAL pupils learn the academic English language required to be successful in examinations. However, it should be noted that there still remain significant differences in attainment with EAL pupils in inner and outer London attaining much better than their peers in other regions such as Yorkshire & Humber where large and persistent gaps in attainment continue to exist. One of the ways EAL learner’s needs should be addressed is by ensuring that teachers are better trained so that they have the requisite knowledge, skills and expertise to teach EAL learners. EAL learners are not a homogeneous group and can have a wide variety of needs. Therefore, it is essential that teachers understand the wide variety of EAL needs and how they can support pupils across all four skills of speaking listening, reading and writing in the lessons they teach, particularly in the academic English required to be successful in examinations. The challenge for teachers is to keep the cognitive demands of the lesson to high level by providing contextual and linguistic support to the EAL pupils in their class. Many teachers will never have had any training or CPD to support them in teaching EAL pupils over the course of their career and as EAL has not been a subject specialism in teacher training for many years now, access to training can be extremely varied, with some Initial Teacher Trainers (ITT) providers preparing their students very well and others not touching this area at all. The above picture is supported by the annual surveys undertaken by the then Teacher Training Agency (TDA) of Newly Qualified Teachers (NQTs) who had successfully completed their ITT. Over the years, whilst the training of NQT’s in this area has improved with approximately 45% of NQT’s stating that their training was good or very good in 2011 – more than double that in 2003, there still remain more than half of new entrants to teaching feeling less well equipped in this area. The graph below shows percentage of NQTS who felt there training was good or very good in preparing them to teach EAL learners and minority ethnic pupils from 2003 – 2011. Source NALDIC and Training and Development Agency for schools (TDA) survey of Newly Qualified Teachers 2011

With the shift in emphasis from Universities and Colleges of Education to Teaching Schools as providers of ITT via the new Schools Direct Programme, the issues highlighted by the TDA annual survey will need to be closely monitored and addressed. Teaching Schools will need to ensure that these new school based programmes prepare and equip NQTs better than before so that they are able to teach currently under –performing groups to the highest standard. The new Teacher Standards 2012 outline the teaching and professional conduct expectations of all teachers. Many of the teaching standards are implicitly relevant to EAL pupils and other groups of pupils too, but standard 5 explicitly states: “A Teacher must ………. · have a clear understanding of the needs of all pupils, including those with special educational needs; those of high ability; those with English as an additional language; those with disabilities; and be able to use and evaluate distinctive teaching approaches to engage and support them”. In this context it is essential that we are preparing all our teachers to understand the needs of our closing the gap groups and our diverse pupil population. Through relevant training and CPD, including Joint Practice Development (JPD), continuing with the example of EAL pupils they can gain in-depth understanding of second language acquisition theory and pedagogy and use appropriate teaching strategies to enhance their own teaching. This would impact on closing the current gaps in attainment that exist for too many EAL pupils, many of whom are of now of second and third generations of communities settled in England. Focusing now on the role of system leaders such as NLE’s, LLE’s and SLE’s who are beginning to drive the development of the self-improving school system. They too have an important role to play in closing the gaps for different groups of pupils. These system leaders in their various roles are providing support to other schools. Many of the schools they are likely to support, albeit not all, have higher concentration of pupils for whom closing the gap remains an issue. The schools they are supporting may be situated in very geographically different contexts to their own schools with the school community facing a plethora a challenges not experienced by the more successful school. They too should be given the opportunity to develop the specialist skills in addressing the needs of different pupil groups for whom closing the gap is an issue, as they may not have had experience of addressing these pupil needs within their own school context or career due to the nature of their pupil cohorts. This additional professional development opportunity which could be delivered by Teaching Schools through their existing leadership development programmes such as NPQH, NPQSL, NPQML[1] or alternatively through bespoke programmes which address the needs of under- performing groups of pupils within their locality. This would no doubt enhance the proven track record and leadership skills these system leaders have already gained in their own schools thus enabling them to be more effective when supporting schools in different contexts. Many Teaching Schools at the moment are running the “Outstanding Teacher Programme” and the ”Improving Teacher Programme” which are without doubt having an impact on improving the quality of teaching in schools. However, these programmes could be even more effective if teachers on these programmes were able to develop the specialist skills required to address the needs of closing the gaps groups alongside generic high quality subject skills. This would mean that teachers were better prepared to teach the actual pupils in their classes and the communities their schools serve. In the case of The London Challenge where these courses were first developed and delivered, there was some flexibility to adapt these courses to meet a variety of needs on this basis. These are exciting and opportune times to make educational changes for the better and if the self-improving school system is to impact on current gaps in attainment not only in terms of EAL pupils but other underperforming groups too, then the new agency has the opportunity to take proactive action to address these areas in an ambitious way by incorporating the suggestions above into all aspects of the new agencies work. This would ensure that the new agency was preparing its teachers and leaders for the current and future needs of its pupils and by doing so realising the ambition of raising standards of attainment across the board. [1] The newly revamped NPQH, NPQSL and NPQML does give aspiring leaders the opportunity to study modules on Closing the Gaps and Achievement for All. However, it is only the NPQSL where the Closing the Gap module is essential. |

Equitable EducationEquitable Education's blog keeps you updated with the latest news and developments in closing the gaps in education. We regularly share best practice materials and case studies of proven strategies to close the education gaps, along with the latest research from the UK and internationally. Archives

July 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed