Over the last few years there has been much emphasis placed on closing the socio-economic gaps in attainment between pupils who are eligible for free school meals and hence receive additional support through the Pupil Premium Grant and those who do not. This is a laudable policy ambition and is worthy of concentrated effort by all of us involved in educating children and young people. However, as with anything, the issues surrounding the closing of the attainment gaps are much more complex than just socio-economic deprivation. In his ground breaking report for Ofsted in 2000 entitled ‘Educational inequality: mapping race, class and gender. A synthesis of research evidence’ Professor David Gillborn showed how these three characteristics impacted on outcomes for different groups of pupils.

3 Comments

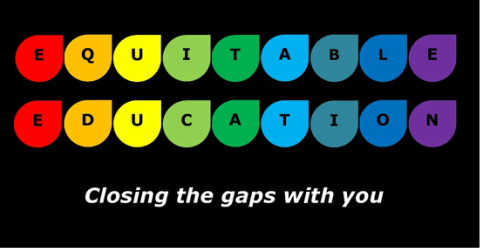

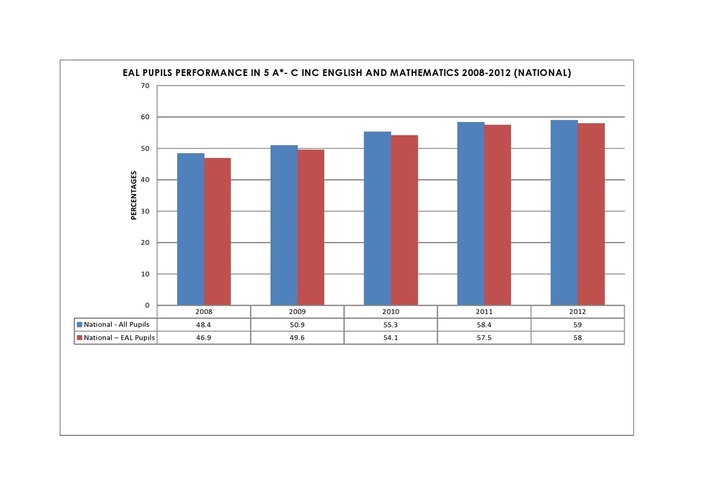

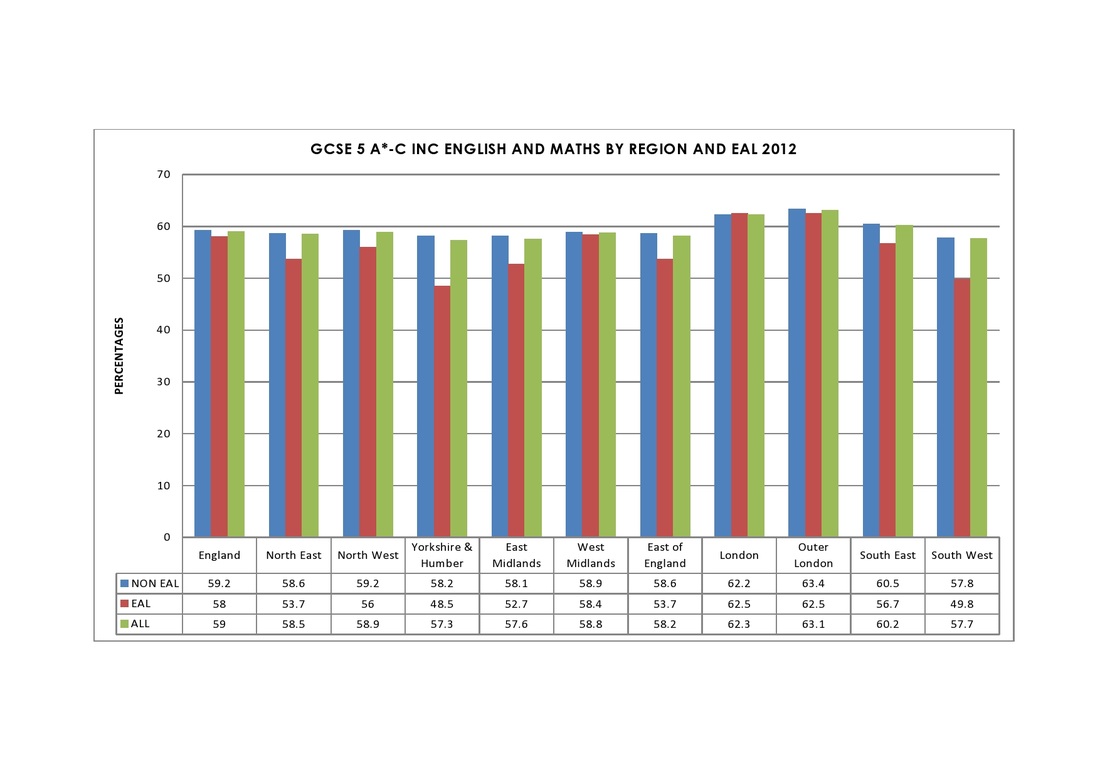

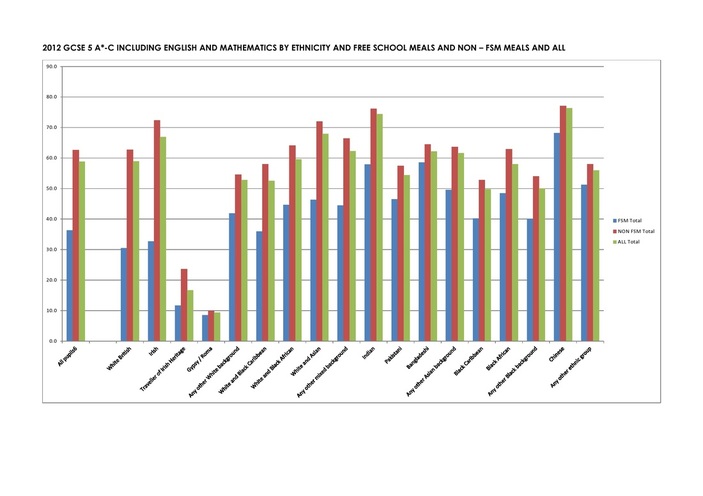

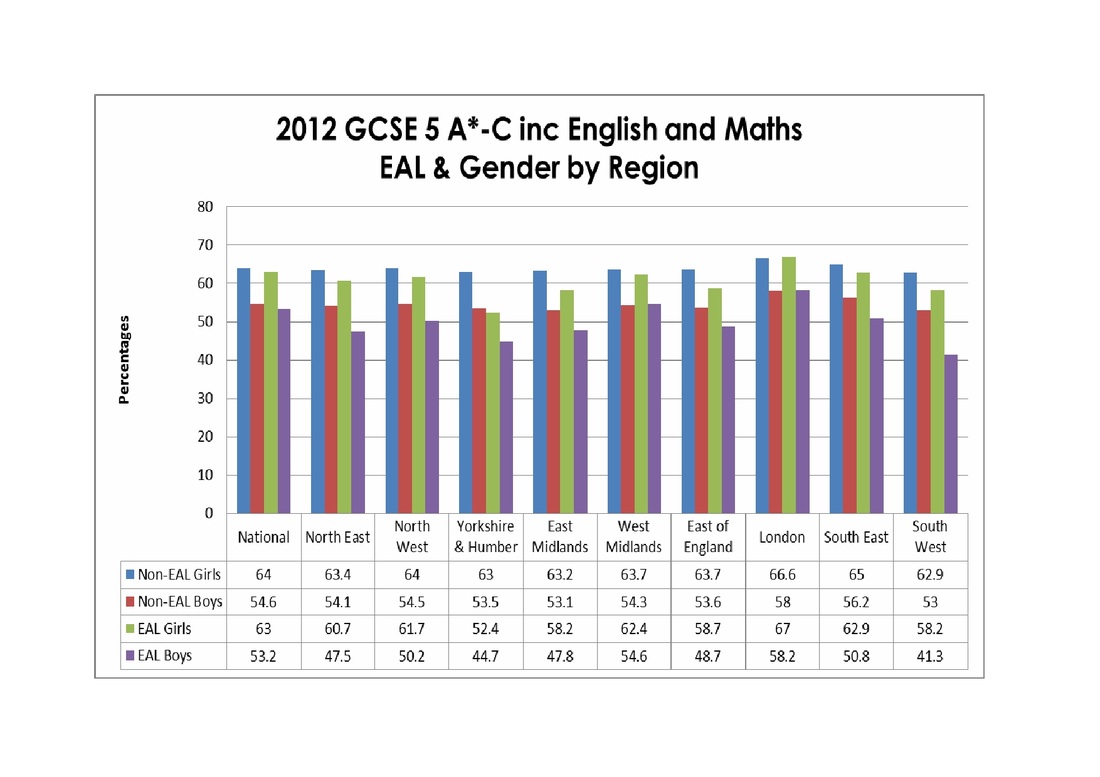

I am currently writing a paper on the present situation with regards to EAL pupils in England, which will cover the following: · Provide an overview of the official approaches to EAL over the past 30 years or so, · Briefly outline associated research into EAL pupil’s both national and international, · The current attainment of EAL pupils in England · Highlight examples of best practice in schools across regions and LA · Stress the urgent need for a more nuanced and focused strategy for pupils for whom English is an additional language at a national level · Outline recommendations The intended purpose of the paper is to encourage reflection, debate and forward strategy at a time when the current education system is undergoing considerable change leading to both potential opportunities and considerable challenges. In such situations there is the strong likelihood that the needs of some groups of pupils are missed especially when the spotlight is shifted to other groups who are deemed more worthy or more in vogue, leading to unnecessary binary approaches to raising attainment. This blog posting summarises some of the key headlines of this paper. The DfE recently released the latest statistics on the number of pupils for whom English is an additional language (EAL). These figures show that there are now over 1 million pupils whose first language is other than English, with the percentages in primary standing at 18.1% compared to 17.5% last year and 13.6% for secondary showing a 0.7% increase on last year. These annual increases show the growing number of EAL pupils in schools in England and are illustrated in the graph below: The trend shows that the numbers of EAL pupils are likely to continue to increase. As a result teaching EAL pupils is now an issue for all schools at a time when many professionals within education report that they do not feel well trained in addressing pupil’s EAL needs (read my earlier blog on EAL and ITE &CPD needs here). The attainment results over the past few years have shown that outcomes for EAL pupils have improved significantly leading to the attainment gaps virtually closing at a national level in terms of the gold standard 5 A*-C including English & Maths grades at GCSE. The graph below shows how the attainment gap at a national level has virtually disappeared over the past five years. These results for the last five years show a vast improvement compared to previously when most EAL pupils were significantly languishing behind their peers. Just a generation ago it was routine for bilingual pupils to be sent to separate language centres to learn English before being admitted to schools. This gradually changed to EAL pupils being sent to language centres within schools and being taught separately until it was felt that they would be able to cope with the mainstream curriculum of their peers. If EAL pupils were extremely lucky then they may have made it directly into the mainstream, escaping the need to receive an alternative curriculum but were often left to sink or swim, without any support or appreciation of their EAL needs. Nowadays these practices would be deemed abhorrent and totally going against well- known research of how bilingual pupils acquire and learn languages. Although these incidents happened approximately 25 – 30 years ago and illustrate the distance that has been travelled so far, they also highlight the journey which still needs to be travelled, until we get to a situation whereby all teachers have the understanding, knowledge and skills to address the needs of EAL pupils within the mainstream context and deliver high quality teaching and learning to enable all EAL pupils attain national expectations. It therefore seems appropriate to briefly take stock of where we are now in relation to meeting the needs of pupils for whom English is an additional language in England and look at the potential of where we should be in the very near future. I have listed a few key headlines below: · At national levels gaps are closing as the graph above shows. These results also mean that some of the powerful negative myths that have perpetuated in relation to bilingual pupils and their attainment are being exploded, resulting in the fact that bilingual pupils can and should achieve academic excellence as a matter of course. · Better outcomes in attainment mean that more EAL pupils have the potential to accrue the benefits of higher education. This should contribute to better opportunities for gainful employment and improved life chances resulting in economic, social and health benefits for many more community members in the future. · Generally most minority ethnic pupils have higher proportions of pupils for whom English is an additional language, with the exception of Black Caribbean pupils. This means that the positive aspects of being bilingual such as those outlined by many academics such as Jim Cummins, Colin Baker, Stephen Krashen, Tove Skutnabb- Kangas and more recently Ellen Bialystok can be used as a lever to support the learning of minority ethnic pupils currently not performing in line with their peers nationally. · Indian and Chinese pupils have been performing much higher than their peers for many years now. Both of these groups have high proportions of bilingual speakers, with over 80% of Indian pupils and 73% of Chinese pupils speaking English as an additional language.[1] More recently the performance of Bangladeshi pupils nationally has also accelerated with impressive performances. Previous reasons cited for Indian and Chinese pupils academic success have been attributed to lower rates of free school meal eligibility in these groups at 12% for Indian pupils and 14% for Chinese pupils. However, the performance Bangladeshi pupils, with one of the highest free school eligibility figures at 52%, add to the growing body of evidence which shows that pupils eligible for free school meals also perform very highly, setting the precedence for others to follow. · There is growing evidence which is exploding many of the myths surrounding EAL pupils. An example of this of is the recent research undertaken by Professor Sandra Mc Nally et al from the London School of Economics, Centre for the Economics of Education. Their research shows that EAL pupils do not negatively impact on standards for non-EAL pupils. For further details read my previous blog here) HOWEVER, despite the seemingly positive picture emerging at a national level, there remain significant CHALLENGES · There are extreme variations in EAL pupil’s attainment by region which the national figures mask. Nationally 58% of EAL pupils in England achieved 5 A*- C in English in Mathematics in 2012. However, EAL pupils in London performed 4.5 percentage points higher at 62.5% compared to those in Yorkshire & Humber who performed nearly 10 percentage points lower at only 48.5%. The graph below shows the regional variations in EAL pupils attainment 5 A*-C in English and Maths in 2012 [1] Figures cited are from ‘Ethnicity and Educational Achievement in Compulsory Schooling’ by Christian Dustmann, Stephen Machin and Uta Schonberg in The Economic Journal 2010. · EAL pupil’s performance within particular LA’s shows further huge variations in attainment with only 32.7% of EAL pupils achieving the gold standard at GCSE in Hereford LA compared to 82.8% of their peers in Kensington and Chelsea or 82% in Sutton. These huge disparities which continue to exist in different LA’s show the necessity to look beyond the national picture. Presently, where you live in England seems to exert a great influence of your educational outcomes which is morally unacceptable. · The success in closing of the gap of EAL pupils nationally can be attributed to a large extent to the higher performance of EAL pupils in London and West Midlands, where there are larger concentrations of EAL pupils, with improvements in London largely due to the success of ‘The London Challenge’. Amongst the various strategies which have been cited in accounting for the success of the London Challenge, the Pan EAL London EAL Strategy is worth highlighting for particular attention. The Pan EAL London Strategy enabled LA’s to receive additional funding to support effective teams to provide support for EAL pupils and to spread this expertise across London. The effectiveness of this work has been highlighted by M Hutchings and A Mansaray in ‘A review of the impact of the London Challenge (2003-8) and the City Challenge (2008-11)’ submitted as evidence to Ofsted’s ‘Access and Achievement’ Review a few months ago. · There are further variations in EAL pupil’s performance when looking at other characteristics such as ethnicity, socio-economic background and gender. Socio-economic gaps are more pronounced for White British groups compared to most ethnic minority groups. For some minority ethnic groups this is because non – free school meal pupils are less likely to come from families with higher socio-economic and professional backgrounds so the differences are less marked. Since national data is not available by ethnicity and EAL, ethnicity data can provide a useful indicator of performance, bearing in mind the intersections of ethnicity and EAL. The differences in performance by FSM eligibility and ethnicity are shown in the graph below: · Bangladeshi pupil’s performance nationally is skewed by the fact that over half of all Bangladeshi pupils live in London, with about a third located in Tower Hamlets alone. Tower Hamlets is one of the success stories and had an impressive 67.8 % of EAL pupils attain 5 A*- C including English and Mathematics in 2012 which is nearly 10 % above the national average. · There are considerable differences in attainment when looking at key stages with outcomes much lower for all minority ethnic and EAL pupils at the start of schooling and even at the end of primary for most groups compared to secondary where most of the gains for EAL pupils are made. This is well documented by researchers.[1] This means the potential outcomes of EAL pupils could be accelerated further if the progress seen in secondary, particularly at KS 4 was replicated in primary. · Gender differences also impact across various regions with EAL girls generally performing much higher than both non-EAL and EAL boys with the exception of the Yorkshire & Humber region where EAL girls performed marginally better than EAL boys but lower than non – EAL girls and boys. The graph below shows how EAL and Gender characteristics lead to extremely differential outcomes across regions with EAL boys in the South West performing the lowest in 2012 leading to a gap of 16.9% compared to their peers in London. [1] ‘The Dynamics of School Attainment of England’s Ethnic Minorities’by Deborah Wilson, Simon Burgess and Adam Briggs CASE paper 2006, ‘A Comparative Analysis of Bangladeshi and Pakistani Educational Attainment in London Secondary Schools’ by Sunder Divya and Layli Uddin 2007, Drivers and Challenges in Raising the Achievement of Pupils from Bangladeshi, Somali and Turkish Backgrounds by Steve Strand et al 2010 and Figures cited are from ‘Ethnicity and Educational Achievement in Compulsory Schooling’ by Christian Dustmann, Stephen Machin and Uta Schonberg in The Economic Journal 2010. · The regional differences are further compounded when looking at the performance in LA’s e.g. only 30 % of EAL boys and 39.3 % of EAL girls in Blackpool LA achieved the gold standard at GCSE last year. This is a stark contrast to the 81.7 % of EAL boys and 84.3 % of EAL girls in Kensington & Chelsea who achieved this benchmark.

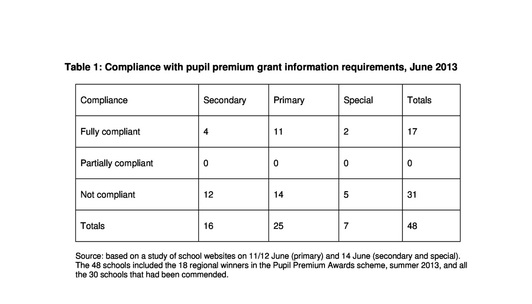

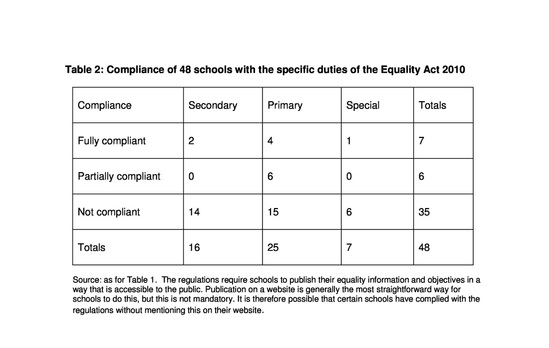

· Another consideration is in relation to the performance of EAL pupils in mainly white LA’s. The issues are complex and may be down to the arrival of newer communities or lack of strategy and expertise in supporting EAL pupils particularly when EAL pupils are dispersed across an LA and are considered to be relatively small. It seems that we in England are at the cusp of making sustained changes in ensuring better educational outcomes for our EAL pupils, many of whom until recently have been languishing behind their peers. Taking a long view there is much to be celebrated and built upon. However, considering the fact that it has taken us over 30 years to get to this stage, with the gains by no means sustained nationally for all key stages and certainly not across regions and LA’s it is imperative that the best practice that is evident is disseminated as a matter of urgency to so that the momentum continues to be built upon. Sadly, although the national results for EAL pupils are applauded there is little if any emphasis on meeting the needs of EAL pupils in other areas or indeed in using flagship policies such as the Pupil Premium to stress the interlinked relationships that exist for EAL pupils and other characteristics such as free school meal eligibility. A more focused and nuanced policy at a national level is required to ensure that the potential of all EAL pupils, irrespective of ethnicity, socio-economic backgrounds and gender is realised and the impact of where you live or which you school you go to does not result in a lottery in achieving better educational outcomes. The headlines are based on a detailed paper which is currently being written by Sameena Choudry on EAL pupils in England and the need for a nuanced strategy to close the gaps. Bill Bolloten, Sameena Choudry and Robin Richardson This article has been republished from LeftCentral. It is also available to read on IPP The pupil premium grant (PPG) is a flagship government scheme for schools. Next week it will be praised and celebrated at the 2013 pupil premium awards ceremony organised in partnership with the Department for Education (DfE). An independent panel of experts has judged which schools have best used the PPG to make a real difference to the attainment of disadvantaged pupils. However, almost two-thirds of the 48 schools that have been named as regional winners or commended for the awards ceremony have so far failed to comply fully with regulations relating to accountability. Also, about four-fifths of them appear to have ignored or misunderstood the regulations concerning accountability in the Equality Act 2010. ‘Take it and use it as you think fit. But …’ ‘Take it, said Nick Clegg in 2011 when introducing the new grant to headteachers, ‘and use it as you see fit.’ He added a stern warning: ‘But know that you will be held accountable for what you achieve.’ The basic principle he was expressing – local freedom combined with public accountability – is central in the coalition government’s public discourse across a wide range of public policy. In the case of the PPG, there are three main ways in which school leaders are held accountable for the decisions they make: a) through the performance tables which show the performance of disadvantaged pupils compared with their peers; b) through the Ofsted inspection framework, under which inspectors focus on the attainment of various pupil groups, including in particular those which attract the pupil premium; and c) the requirement to publish online information about the pupil premium for parents and others. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has noted with approval that the UK government requires schools to report to parents on how they have used additional money to close gaps in attainment connected with poverty and economic disadvantage. How schools present the information in their online statement for parents is a matter for each school to decide for itself. There is certain minimum key information, however, which must by law be included on a school’s website. The amended school information regulations relating to this came into force in September 2012. Yet, as of June 2013, it appears that only a third of schools in receipt of the grant are fully complying with it. Background Monies previously allocated to other priorities have been redirected since 2010 towards children from low-income households, defined for the purposes of allocating the grant as those who are eligible for free school meals, or who have been eligible at any time in the last six years, and whose parents or carers have registered for free meals (though they may not have actually claimed them). Schools also receive funding for children who have been looked after continuously for more than six months, and for children of service personnel. In the last financial year the grant was £623 per pupil. Since April 2013 it has been £900 per pupil. For children of service personnel it is £300. The grant does not have to be spent only on pupils who are eligible for free school meals. Its use must, however, be directed towards reducing or closing gaps in attainment connected with poverty and economic disadvantage. The total annual funding will be £2.5 billion by 2015. In his spending review announcement on 26 June 2013 Chancellor George Osborne pledged that the grant will continue in real terms – ‘so every poor child will have more cash spent on their future than ever before’. In order that schools can be accountable to parents and others, they are required to publish on their website 1) their PPG allocation in respect of the current academic year, 2) details of how it is intended the allocation will be spent, 3) details of how the previous academic year’s allocation was spent, and 4) the impact of this expenditure on the educational attainment of pupils at the school in respect of whom the grant funding was allocated. Study of 48 shortlisted schools In June 2013 a study was made of the websites of the 48 schools –16 secondary, 25 primary, 7 special – that are regional winners or commended in the pupil premium awards scheme. Schools were judged in this study to be fully compliant with the statutory school information regulations if they had published all four of the required pieces of information; partially compliant if they had published at least three; and non-compliant of they had published no more than two, or had published nothing at all. Schools applied for the award on the basis of criteria that did not mention the requirement to publish information for parents. The picture relating to the 48 schools shortlisted in the PPG awards is shown in Table 1 below. The Equality Act 2010 Principles of transparency and accountability determine not only how the pupil premium grant operates but also how public bodies are required to show due regard for the aims of the Equality Act. Under the Act’s specific duties, schools must a) publish information that demonstrates adequately an awareness of the diversity of the school population and how have had due regard for the aims of the Act, and b) prepare and publish at least one specific and measurable equality objective. To count as specific, an objective should state the outcome that the school aims to achieve. To count as measurable, the desired outcome must be quantifiable so that parents and the community can assess whether the school has been successful. In order to determine their compliance with the accountability rules in the Equality Act, a study was made in June 2013 of the websites of the 48 schools featured in the pupil premium awards scheme. A school was judged to be fully compliant if it had published relevant information and at least one specific and measurable equality objective. It was judged to be partially compliant if it had published either equality information or measurable equality objectives, but not both, or if it was clearly aware of the duties even if it did not appear to have understood them. It was found that almost three-quarters of the schools shortlisted for the pupil premium awards (35 out of 48) failed to comply at all with the requirement to publish equality information and objectives. Less than one in six of them complied fully. The overall picture is shown in Table 2. Concluding notes

The 48 schools whose websites were studied for this article are probably all making good use of the pupil premium grant, and the judges who selected them for special praise have made good decisions. It is surely surprising, however, that so many have not complied with regulations relating to accountability. The principal reasons for non-compliance appear to lie in the failure of the government to provide adequate advice, guidance, challenge and support. Most of the schools which are non-compliant are probably unaware of the regulations and requirements, for the government has been generally light-touch in its publicity about them. Prior to 2010 schools would have received advice and support in relation to a project such as the pupil premium grant from their local authority. There would have been training and professional development opportunities, exchange of information about relevant research findings, and – crucially – much collaboration and joint reflection within local clusters and families of schools. Local networking along such lines is now much more problematic. It continues, however, to be an urgent necessity, and is a matter which requires the government’s attention. Guidance, research and commentaries on the pupil premium grant have recently been published by, amongst others, the Sutton Trust, the Institute for Public Policy Research, the Department for Education and the Young Foundation. These reviews are much more substantial than the small-scale survey reported in this article. Their recurring conclusion, however, is that schools need more advice, training and challenge than they have so far received. Understandably and rightly the government does not wish to micro-manage what happens in schools. It nevertheless has a responsibility to ensure that good practice is widely shared. With the declining capacity and influence of local authorities, this responsibility is of urgent importance. At the same time, the government needs to lead consideration of the links, connections and similarities between economic inequality and other forms of inequality, particularly those which are highlighted in the Equality Act. Each pupil stands at the intersection of several different strands of equality and inequality. For example, every child from a low-income household not only has a socio-economic location affected by poverty but also is a boy or a girl and has an identity in terms of ethnicity; many have special educational needs amounting to a disability; many have a religious identity which is important to them; all have a sexual identity. Some of a child’s educational needs cannot be appropriately met without reference to distinctive aspects of their experience, identity and reality – they are not ‘all the same’. One universal size does not fit them all. Schools should therefore be encouraged both to explore intersectionality in their use of the premium grant and to pay due regard to economic disadvantage in their responses to the Equality Act. This is especially crucial in view of the fact that low income frequently intersects with the issues named in the Equality Act, particularly in relation to ethnicity, religion and disability. Overall, about 18 per cent of all young people are eligible for free school meals and therefore for the pupil premium grant. But for white pupils the proportion is slightly smaller, 16 per cent, whilst for certain others it is considerably higher. For children with special educational needs it is twice as high as for other children. ‘It is unacceptable,’ said the coalition government when it came to power in 2010, ‘for educational attainment to be affected by gender, disability, race, social class, sexual orientation or any other factor unrelated to ability. Every child deserves a good education and every child should achieve high standards. It is a unique sadness of our times that we have one of the most stratified and segregated school systems in the world …’ Such ideals and concerns sound like empty rhetoric if schools do not comply with rules of accountability. Bill Bolloten tweets at @SchoolEquality and Robin Richardson at @Instedconsult. There is further information at www.insted.co.uk (Robin Richardson). Yesterday, I was visited by my four year old nephew. As most four year old he is still at an age where he is curious about his surroundings. He was fascinated by the magnets I have stuck to my fridge. Most of them have been collected as souvenirs whilst on holidays abroad. He went through the magnets and wanted to know which country they were from. He was particularly taken by this one similar to the picture below bought from Marrakech which had the Arabic alphabet colourfully displayed. I asked him if he could read any of the letters. He was able to read out a few at the beginning - Alif for the ‘a’ sound and Baa for the ‘b’ sound and then tuned to me and said in a serious tone, ‘ You do know though Aunty, you can’t speak Panjabi at school. You have to speak English…’ I asked him why that was the case and he replied, ’You just have to speak English’. Now, I wasn’t surprised by this statement, as I myself many years ago had gone through similar experiences as a bilingual child and knew instinctively that my language was something that was not valued at school and that there was no room for it to be used within the classroom context. That was many years ago and was indicative of the times. Indeed, it was quite common for children to make fun and ridicule any languages other than English being spoken. They obviously weren’t aware of the hours of endless fun you could have by ‘code switching’ or making your own unique language up by mixing the languages, so that it was only understood by speakers of both languages.

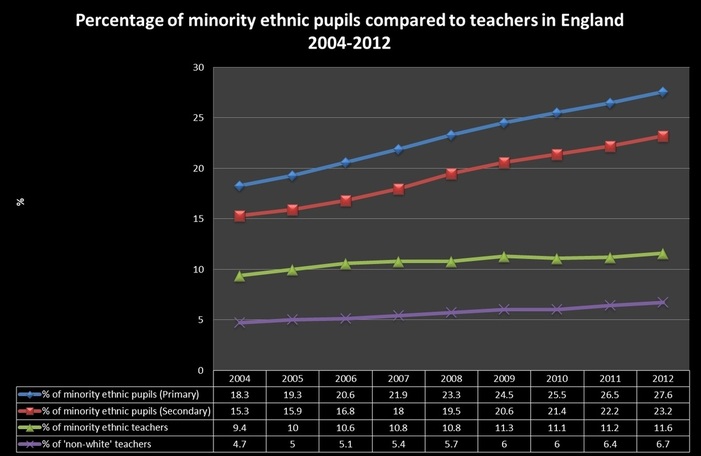

Due to my own interest in languages and multilingualism in a particular, I decided that I would ensure that my own children would be fluent in their mother tongue Panjabi and become proficient in Urdu (written in the Perso- Arabic script, hence my nephews comments on the Arabic Alphabet) because of the valuable role that it plays as a Lingua Franca [1] across the Indian subcontinent, not mentioning its popularity across the world for many reasons, including its prevalence in Bollywood movies many of whom use Urdu and Hindi. I therefore, made a conscious effort to give my children the opportunity to learn both languages in a natural way as possible, ensuring that they had a wide range of bilingual books at their disposal to reinforce the use of both Panjabi and Urdu within the family. What I found surprising, especially in the case of my son, who is now 15 years old was that within a term of going to Reception, more or less the same age as my nephew, he refused to speak in any language other than English. Now as it happens, both my children and now my nephew go to the same school. The school is a larger than average primary school, with very low levels of FSM and approximately 12.5 % of EAL pupils. They generally provide a good education and in their own way promote diversity, certainly more than when I was at school but despite this the effect on my nephew was the same as it has been for me and my children. The net result of this is that potential bilingual or even multilingual children are gradually undergoing ‘language loss’. This phenomenon is occurring across many settled communities. At best children and young people growing up are only able to develop receptive skills in languages used within the community but are not able to use these skills productively as English becomes the dominant languages which is increasingly used in all domains. This anecdotal story illustrates the powerful monolingual message which continues to play a dominant role in England today. Ironically, this is in strong contrast to the message given by politicians and the media which states that communities choose NOT to speak English. I don’t think I have ever come across anyone who has resisted the need nor discounted the importance of learning English. It is disingenuous to talk about settled communities not speaking English, especially when extensive research from different parts of the world show that many communities suffer language loss within a generation as in the case in personal example given above. Indeed, a language survey undertaken by www.ethnicpolitics.org shows how English is now used by more bilingual communities within the home context too. In their initial survey which was undertaken in 1997, 56% of the minority ethnic members surveyed stated that they used English at home compared to 44% who stated they did not. There were of course underlying differences for the various different communities. By 2010 the responses to the same survey showed that this trend has completely reversed with 64% of minority ethnic members now stating that they used English at home compared to 36% who said they did not, with these significant changes having taken place over a period of just 13 years. Furthermore, the critics who like making a fuss about the learning of English choose to ignore the fact that the 2011 Census showed that of the 51,005,610 English population taking part in the census (residents aged three and over) 46,936,780 of them had English as their main language. For the remaining 4,068,830 for whom English was not their main language, 3,224,830 spoke English either very well or well, with a further 709,862 stating they could not speak English well. Only a small proportion of the overall population, a mere 133,983 stated that they could not speak English. [2] More importantly for me the issue is that you don’t just have to know one language. It is possible to be proficient in more than one language without it being detrimental to learning, which sadly was the WRONG view perpetuated in the days when I was growing up. Indeed, there are many benefits that accrue from being bilingual, notwithstanding the cognitive benefits which teachers could use to aid learning in the classroom. We really do need to ensure that our schools are more supportive of the learning of languages, both Modern Foreign languages and ‘community languages’. Sadly, the new proposed MFL national curriculum proposes a hierarchy of status for languages in which the languages spoken by many of our settled communities are not recognised at all. This is just plain wrong and it is such omissions in practice and policy which so powerfully give the message to all children, whether monolingual or not that languages other than English are not important, unless of course they happen to be on the ‘list’ which then are reserved for the elite few who are deemed capable of studying languages. It’s about time we started valuing all languages, so that we move away from the deficit approach that is common in England and build upon the rich linguistic capital that exists within our communities. Just as a final note to ponder. We could take a broader view of many of these so called ‘community languages’ which are spoken by millions of people in the world. Take for example the three Indo-Aryan languages mentioned in this posting, which I like many others of my generation, are lucky to have as part of our linguistic capital – Urdu, Hindi and Panjabi. These three languages are mutually intelligible. According to the total number of speakers for these languages in 2007, there were 295 million speakers of Hindi, 96 million of Panjabi and 66 million of Urdu in the world.[3] If you add these three languages together you come to a grand total of 457 million speakers, which is the equivalent of 6.89 % of the world’s population. In the same year, the total number of speakers of English was 365 million or 5.52% of the world population. Not so much of ‘community languages’ after all, when you take a wider global perspective. This should certainly give us food for thought as we are increasingly required to navigate in a globalised world, where the language competencies that are required are more varied and which mean that we cannot continue to be solely reliant on English is a dominant language. It's time for us to wake up and embrace the fact that over half of the world’s population is bilingual and it is the norm across all social groups and ages and many of the languages that could be used naturally by our children are gradually being taken away at a loss to them and society as a whole. [1] The use of Panjabi, Urdu and Arabic within Pakistani heritage community is not explored here but will be covered in another posting later, as well as the relationship between Urdu, Hindi and Panjabi. [2] Source Office for National Statistics, 2011 Census Proficiency in English, local authorities in England and Wales (Excel spreadsheet) http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/search/index.html?newquery=english+language+use [3] Source http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_languages_by_number_of_native_speakers The potential for Teaching Schools and a school led system to make the workforce more representative of its local pupil population. A few days ago the DfE published its annual School Workforce in England Report. This report provides a wealth of information on the size and characteristics of the school workforce working in schools and academies, including ethnicity profiles of staff. As I have both a personal and professional interest in matters pertaining to equality and diversity, I read the report with interest to take stock of the current situation with regards to the make up of our school workforce. This year’s data highlighted the stark realities facing the English education system, whereby the profession remains overwhelmingly white at a time when the pupil population is becoming increasingly diverse. Statistics from the report show that 94.4% of Heads of publically funded schools are from a ‘White British’ background. However, considering the fact that this means the remaining 5.6% ‘ethnic minority’ category also includes 1.8% of Heads from ‘Any other white background’ and 1.3% from ‘White Irish’ background, the figures are even more alarming if you look at the ‘non-white’ representation of Heads which stands at a paltry 2.5%. The situation regarding teachers is a little better with 88.4% of teachers coming from ‘White British’ backgrounds overall, but again the figures drop considerably when looking at just ‘non-white’ teachers, which represent only 6.7% of the teaching workforce. This is an increase of 0.3% on last year. Behind this headline data, the report also shows that there are higher percentages of minority ethnic teachers and senior leaders in the London region, highlighting considerable regional disparities too. I was disappointed with these figures, so decided to take a longer view of the situation rather than judging the improvements over one year. I therefore went through each annual ‘School Workforce’ report and was able to go back as far as 2004, when the first set of disaggregated data became available. I also wanted to look at what was happening in our schools in relation to the pupil population and was able to get the figures for the minority ethnic pupil profile from the annual ‘Schools, pupils and their characteristics’ reports for the same period. My findings are presented in the graph below, which plots the percentage of England’s minority ethnic pupil profile separately by Primary and Secondary phase from 2004 to present, along with both its minority ethnic (green line) and ‘non-white’ (purple line) teacher profile over the same period. Data Sources:

DfE: Schools, Pupils and their characteristics, Statistical First Release for individual years 2004 -2012 DfE: School Workforce in England, Statistical First Releases for individual years 2004-2012 The graph doesn’t need much commentary because the visual representation tells the tale quite vividly. What these figures reveal is that the percentages of minority ethnic and ‘non-white’ teachers have increased more or less every year leading to an overall 2% gain over this period. However, as can be seen in the graph these increases are occurring at a painfully slow rate. Certainly during the past eight years the percentage of minority ethnic pupils has increased at a faster rate, so that the gaps are widening considerably year on year and will continue to do so unless some decisive action is undertaken. For many years in England there has been a recognition and understanding by policy makers of the many benefits which can accrue from having a school workforce which is reflective of its pupil population. It has also been recognised that minority ethnic teachers can play an important role in ensuring that all pupils get a more balanced view of society and as far back as 1985, when I first entered the teaching profession, The Swann Report and later the Cantle Report in 2001, highlighted the need to ensure that the teaching ethos of each school reflected the different cultures of the communities served by society and that the lack of ethnic minority teachers in schools needed urgent attention. The now abolished Teacher Development Agency (TDA) oversaw a number of initiatives through which Initial Teacher Training (ITT) institutions were actively encouraged to recruit and retain minority ethnic staff in schools. The National College similarly has led a number of initiatives to encourage better representation of minority ethnic teachers to progress to senior leadership levels, such as the Equal Access to Promotion (EAP) and Investing in Diversity (IiD) Programmes. During this time there have also been a number of important reports commissioned to look in depth at the disparities that exist and the reasons for this, such as joint report by NASUWT and NCSL entitled ‘The leadership aspirations and careers of black and ethnic minority teachers’ undertaken by The University of Manchester. This report along with several others provides useful information to ascertain the issues and possible ways forward for interested parties, although generally there is a dearth of research in this area both in England and internationally. This issue is not only pertinent to England as many countries across the world are also grappling with similar issues to varying degree of success. An OECD report called ‘Educating Teachers for Diversity: Meeting the Challenge’ in 2010, explores the concepts underlying diversity in various contexts across the world and the challenges involved in creating an evidence base to guide policy makers. This report focuses on two key areas: · Preparing all teachers for meeting the needs of an increasingly diverse pupil population and · Ensuring the school workforce is representative of the pupil population It urges schools and education systems to ‘treat diversity as a source of potential growth rather than an inherent hindrance to student performance………’ and argues for a paradigm shift from homogeneity, to heterogeneity and finally to diversity by moving along a continuum, whereby difference is not acknowledged under homogeneity, differences are seen as a challenge to be dealt with under heterogeneity, to difference seen as an asset and opportunity under diversity. In England, the challenge for us is to move from heterogeneity to diversity and accelerate our efforts in in this endeavour. With the rapidly changing education system within England, it seems that the current developing autonomous school system led by Teaching School Alliances and their partners could provide an opportunity to embrace these issues by ensuring that decisive action is taken at a local and regional level to make the school workforce more representative of the pupil and communities they serve. Teaching Schools have been given the remit of recruiting and retaining the best teachers and leaders and providing high quality Continuous Professional Development (CPD) opportunities for staff at all levels of career progression. They also have a remit to focus on succession planning issues. The National College Teaching School handbook in the section ‘Diversifying School Leadership’ gives clear pointers for serious consideration. Dependent on the understanding and expertise of diversity matters within individual Teaching School Alliances, which may or may not be a current area of strength, there is the powerful potential of taking forward what has already worked well by successful ITT institutions in this area and ensuring this is embedded in newer programmes such as Schools Direct, which are increasingly being delivered locally by schools. It also provides an opportunity to carefully look at the existing programmes being delivered through Teaching Schools to ensure that action is taken to recruit and retain minority ethnic teachers and where gaps in provision are evident, bespoke solutions are developed. With careful analysis of local needs in relation to diversity matters there is the unique possibility for each Teaching School Alliance to develop a clear and cogent strategy of building on the existing best but also innovating to fill existing gaps, so that there is acceleration in percentages of ethnic minority teachers and Senior Leaders at local and regional level, in line with the paradigm shift argued for within the OECD report. This would enable England to become a world leader in this area for other countries to emulate. |

Equitable EducationEquitable Education's blog keeps you updated with the latest news and developments in closing the gaps in education. We regularly share best practice materials and case studies of proven strategies to close the education gaps, along with the latest research from the UK and internationally. Archives

July 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed